The main lesson of this year’s transfer window

is that UEFA’s Financial Fair Play (FFP) rules have a true bite (no pun

intended). Surely, the transfer fees have reached usual highs with Suarez’s

move to FC Barcelona and Rodriguez’s transfer from AS Monaco to Real Madrid and

overall spending are roughly equal to 2013 (or go beyond as in the UK). But clubs sanctioned under the FFP rules

(prominently PSG and Manchester City) have seemingly complied with the

settlements reached with UEFA capping their transfer spending and wages.

FFP's Transfer Diet

PSG’s

summer of impuissance

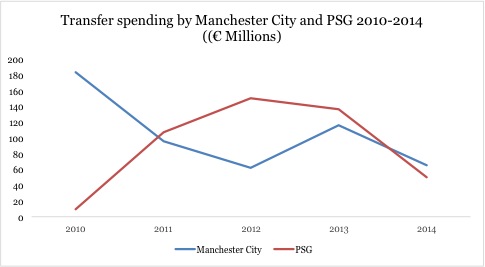

It was widely expected, and trumpeted, that PSG

and Manchester City would disregard the transfer restrictions imposed on them. Besides

all the talking and the costly recruitment of David Luiz for nearly 50M€

earlier this summer, PSG’s transfer activity was limited to Serge Aurier’s

arrival on loan from modest Toulouse. Moreover, the talks over Di Maria’s move

to PSG faltered over the inability of the French club to pay a

transfer fee due to the FFP constraints. Thus, PSG was forced into relative thrift by the FFP rules, a

remarkable achievement in itself. This has recently triggered widespread critique against UEFA and FFP by PSG officials.

Manchester City overtaken by Manchester United

Even though Manchester City has largely

dominated the transfer contest against its arch-rival over the latest years,

this balance has dramatically tilted during this summer. United was able to

attract a number of high-ranked and expensive players, most notably Di Maria

for the total sum of 66M€ (more than City’s total spending). In a final

transfer twist, United was even able to snap away Falcao from City apparently due to FFP concerns. City did

not engage in the usual frenzy spending spree of the previous years. It did

spend around 60 M€ (and racked in 25M€ in transfer fees), but this number pales

in regard to the 116M€ spent in 2013. Here again, despite talks to the contrary

and vouching to disregard UEFA’s FFP rules, one cannot ignore the toll taken by

them on the capacity of Manchester City to outrageously dominate the

UK transfer market.

The

general timidity of FFP culprits

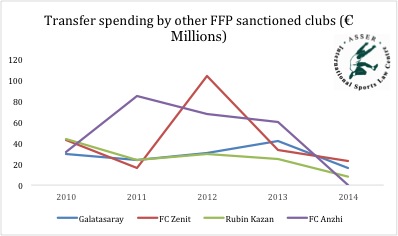

This is not an isolated development. Other

clubs concerned by FFP settlements have followed a similar path (see graph below).

In general, clubs sanctioned under FFP rules have reduced their transfer spending

in comparison to previous years. More surprisingly, big players like PSG and

Manchester City have complied with the net transfer limit of 49M€ imposed on

them in the settlement. This points at an apparent success of the FFP

regulations, which have not materialised, as many feared, as a public relations exercised in the guise

of a toothless regulation. The rules have a real-world impact, and in spite of

the high profiles of certain clubs concerned those have felt the urge to

internalize them reinforcing UEFA’s claim that FFP is a serious regulation. As

will be shown below, however, this also supports the claims that FFP

regulations constitute a restriction on competition in need of adequate

justification.

New strategies to bypass FFP rules

This development has also led clubs to devise bypassing

strategies to the FFP rules. The first strategy is to use loans as temporary or differed transfers by

including a mandatory transfer clause in the contract. This is the solution

adopted by PSG in the transfer of Serge Aurier from Toulouse. In a way there is

no reason why this should not be considered as a new liability for accounting

purposes, as it is akin to a delayed payment but not to a delayed transfer.

Finally, there is the possibility of using affiliated clubs to store the

long-term liabilities (wages and fees), while getting a player on short-term

loans. This is likely the strategy used by Manchester City in the now infamous

recruitment of Frank Lampard from its sister club New York City FC. Hence, one

should not underestimate the ability of clubs to sidestep the FFP rules, albeit

a way more difficult and protracted transfer game as before.

FFP’s compatibility with EU competition law

still a threat

Does this real-world efficacy change anything to

the assessment of FFP’s compatibility with EU competition law? Not really. On

the one hand, it is all the more evident that the FFP rules have a restraining

effect on free competition; certain economic actors are undoubtedly not free to

invest their money, as they would see fit. On the other hand, the real test for

evaluating the FFP’s compatibility with EU law is the Wouters/Meca-Medina

proportionality test developed by the EU Court. First of all UEFA will have to

identify the legitimate objective it intends to pursue with these regulations.

This is likely to be good corporate governance, as one cannot consider that FFP

rules improve the competitive balance by reducing the inequality between clubs in

the absence of any redistributive effects. Actually, FFP will most likely

sclerotize the pre-existing hierarchies. If good corporate governance in

football is deemed a worthy objective (it probably will), the next question

will be: are these regulations a proportionate mean to achieve it? At this

stage UEFA will need to explain why the existing national bankruptcy frameworks

are inadequate for this purpose (due, for example, to the political influence

of clubs like in Spain, or to the particular feature of football competition that

cannot tolerate the vagaries of a normal bankruptcy process), but also why the

existing debt stock is not taken into account by the rules. Here, the brunt of

the socio-political debate on the need of FFP will unfold.

As UEFA’s FFP rules strengthen their grip over

clubs, they will be more and more incentivized to contest the rules in front of

the EU Commission (PSG and Manchester City fans have recently submitted a complaint) or national tribunals. Thus,

these questions will not remain hypothetical and will have to be met by UEFA

with hard facts and convincing arguments. If not the FFP rules will be

remembered as an ephemeral, though remarkable, interlude of the summer 2014.

|

Clubs

|

Amount

spend on transfers in 2010 (in millions)

|

2011

|

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

|

Manchester City

|

€182.45

|

€96.05

|

€61.95

|

€116.0

|

€65.5

|

|

PSG

|

€9.0

|

€107.1

|

€149.45

|

€135.9

|

€49.5

|

|

Galatasaray

|

€29.5

|

€23.6

|

€30.05

|

€41.84

|

€15.75

|

|

Trabzonspor

|

€7.9

|

€24.45

|

€8.06

|

€4.7

|

€29.11

|

|

Bursaspor

|

€1.38

|

€10.2

|

€3.66

|

€2.33

|

€1.8

|

|

FC Zenit

|

€43.0

|

€16.2

|

€103.76

|

€32.8

|

€22.8

|

|

Rubin Kazan

|

€43.6

|

€23.35

|

€29.0

|

€25.1

|

€8.0

|

|

FC Anzhi

|

€31.2

|

€84.5

|

€67.9

|

€59.4

|

€0

|

|

Levski Sofia

|

€0.8

|

€0.95

|

€1.25

|

€0.59

|

€0.05

|

Data from transfermarkt.com