On 12 January 2017 UEFA published its eighth club licensing benchmarking report on European

football, concerning the financial

year of 2015. In the press release that accompanied the report, UEFA proudly announced

that Financial Fair Play (FFP) has had a huge positive impact on European

football, creating a more stable financial environment. Important findings included

a rise of aggregate operating profits of €1.5bn in the last two years, compared

to losses of €700m in the two years immediately prior to the introduction of

Financial Fair Play.

Source: UEFA’s

eighth club licensing benchmarking report on European football, slide

107.

Meanwhile the aggregate losses dropped by 81% from

€1.7bn in 2011 to just over €300m in 2015.

Source: UEFA’s

eighth club licensing benchmarking report on European football, slide

108.

Furthermore, net debt as a percentage of revenue has

fallen from 65% in 2009 to 40% in 2015.[1]

Source: UEFA’s

eighth club licensing benchmarking report on European football, slide

125.

UEFA’s Financial Fair

Play vindicated?

As was clear from the UEFA Club Licensing Benchmarking Report Financial Year ending 2011, the deficit of clubs with a UEFA License increased from

€0.6 billion in 2007 to a peak of €1.7 billion in

2011, with some historic European football clubs, like FC Parma, going

bankrupt. Though the increasing indebtedness might

have been to a large extent related to the global economic crisis[2],

UEFA considered that it was mainly the result of irresponsible spending by the

clubs.[3]

Consequently, UEFA introduced the FFP Regulations, whose objectives are, inter alia,

improving the economic and financial capabilities of clubs; introducing more

discipline and rationality in club football finances; encouraging clubs to

operate on the basis of their own revenues; and protecting the long-term

viability and sustainability of European club football. UEFA’s primary tool to achieve those is the break-even

requirement imposed on clubs having qualified for a UEFA club competition.[4] Accordingly, clubs must demonstrate that their expenditure does not

exceed their revenue should they wish to avoid sanctions by the

UEFA Club Financial Control Body.[5] With these objectives in mind, it does not come as a

surprise that UEFA is celebrating in this report the success of the FFP

regulations.

The negative side

effect of FFP: The rise of the 1%

The FFP regulations are still facing

controversy and legal challenges in spite of (or, maybe, because of) the results highlighted in this report. As early as

2012, critics pointed out that FFP could nurture the competitive imbalance between European football clubs. Basically, a successful club will yield more revenue,

leading to the club being able to afford better players, in turn leading to the

club being more successful, and so on and so forth. Since small clubs are no

longer allowed to overinvest their way to a greater market size in the future,

people predicted that FFP would trigger an era of competitive imbalance.[6]

Indeed, this competitive imbalance was one of the primary arguments used by player agent Striani and his

lawyer Dupont in their complaint to the

European Commission.[7]

UEFA has so far successfully managed to withstand the legal

challenges launched against the FFP

rules, such as a Commission complaint, a preliminary reference to the Court of Justice of the EU, challenges in front of Belgian courts, a challenge in front of a French court, and

a challenge in front of the Court of Arbitration for Sport. However, it is now forced to acknowledge that “the

top 15 European clubs have added €1.51bn in sponsorship and commercial revenues

in the last six years (148% increase), compared to the €453m added by the rest

of the approximately 700 top-division clubs in Europe (17% increase)”.[8]

UEFA is clearly concerned about the increasing gap between the “global super clubs” and the rest, though it is adamant that

“overspending and unsustainable business models cannot be the answer to financial

inequality”.[9]

Nonetheless, it is not completely fair to argue that by

attempting to solve one problem (i.e. reducing the increasing debts of football

clubs) UEFA single-handedly created

another problem (i.e. the growing inequality between the global super clubs and

the rest).[10] There

are of course other factors that contributed to this increasing financial gap,

most notably the discrepancies in incomes derived from the selling of media

rights at national level. As can be seen in UEFA’s latest Benchmarking report,

English Premier League clubs received an average of €108m for their media

rights in 2015. This figure is considerably higher than other clubs from the

“top five leagues”, namely the Italian (€47.7m), Spanish (€36.7m), German

(€36.1m) and French clubs (€24.9m).[11]

In fact, 17 out of the top 20 clubs by broadcast revenues in 2015 are English,

the other three being Real Madrid, FC Barcelona and Juventus.[12]

Nonetheless, even though UEFA is not responsible for the differences in media

rights revenue, the FFP Regulations remain a clear obstacle for clubs from

other leagues to get investment from alternative sources.

What has UEFA done to

counter this growing inequality?

The pressing question on many people’s mind is whether

UEFA will, or even can, do something

about the ever-growing financial inequality between football clubs. The FFP Regulations

can be changed, as was demonstrated in 2015. An important innovation in this

regard was the introduction of Annex XII on voluntary agreements with UEFA for

the break-even requirement. Under this Annex, UEFA allows, inter alia, a club to

apply for such an agreement if the club has been subject to a significant change

in ownership and/or control within the 12 months preceding the application

deadline.[13] When

applying for a voluntary agreement the club will (among other obligations) need

to:

- submit a long-term business plan, including future break-even information;

- demonstrate its ability to continue as a going concern until at least the end of the period covered by the voluntary agreement;

- and submit an irrevocable commitment by an equity participant (i.e. shareholder) to make contributions for an amount at least equal to the aggregate future break-even deficits for all the reporting periods covered by the voluntary agreement.[14]

The relaxation of the FFP Regulations to leave more

room for investment has probably led to an increase of foreign acquisitions of

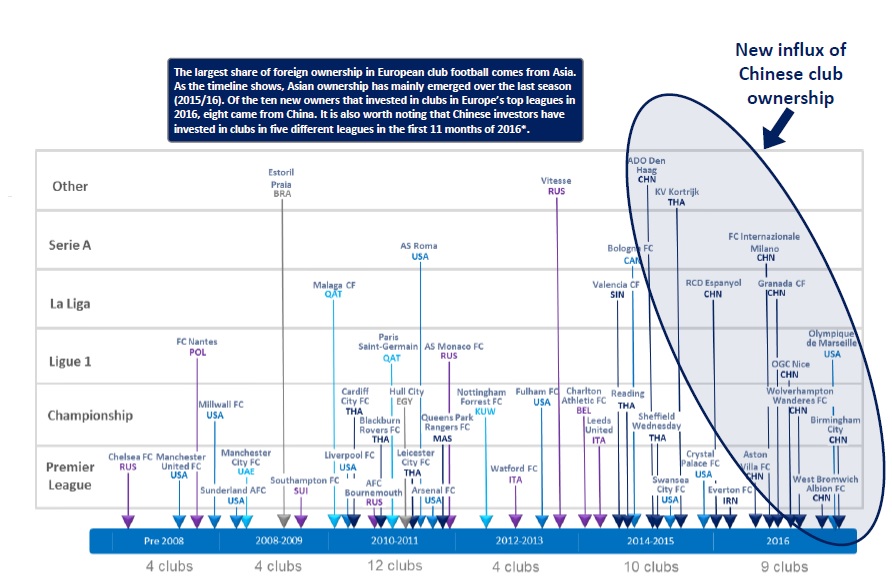

European football clubs. As the graph below shows, only four clubs were bought

by non-Europeans in the years 2012 and 2013, a period in which a stricter version

of the FFP Regulations was in force, whole nine clubs were bought in 2016

alone, seven of which were bought by Chinese investors.

Source: UEFA’s

eighth club licensing benchmarking report on European football, slide

56.

Nonetheless, upcoming media rights deals will ensure

financial inequality for years to come, regardless of any particular FFP relaxation. It is estimated that Premier League clubs will receive an

average of €141m per season for the 2016/17 – 2018/19, while e.g. Spanish clubs are predicted to make an average

of ‘only’ €64m for the 2016/17 season.[15] Meanwhile,

the highest earning Dutch club (Ajax) is expected to make a meagre €9.3m from the selling

of its media rights for the 2016/17 season.

Conclusion: Can UEFA equalize?

With the financial gap between clubs increasing instead of decreasing,

should UEFA’s regulatory focus shift from good corporate governance (limited debt,

small deficit) to redistribution and the fight against inequalities in

football? The recently installed UEFA President

Aleksander Čeverin held that “UEFA, together with its stakeholders, will need

to continuously review and adapt its regulations”[16],

but it is unclear what concrete adaptations he has in mind.

Possible options to tackle inequality would include:

limiting media rights income; sharing media rights income at a European level;

introducing salary caps; or even introducing a solidarity mechanism that would

oblige clubs to redistribute some of their income to poorer clubs.[17]

However, such proposals will always be strongly resisted by rich clubs, which

are in a position to threaten to put in place a breakaway league at any time.[18]

UEFA is hardly equipped to resist them. Unless UEFA’s regulatory monopoly is

fully recognized and endorsed by the European Commission, it will not be able

to face down a breakaway rebellion. Instead, it risks facing a FIBA-like

bitter and costly secession. Hence, for

UEFA the status quo remains the safest option, and facing criticisms from small

clubs way less harmful economically and politically.

A final option, favoured by the many opponents of FFP,

would be to abandon FFP all together. This way, there would be no more

restrictions to (private) investors willing to pour their (often borrowed)

money in (European) football clubs. However, it would also imply renouncing the

key achievement of FFP, European football clubs are financially way healthier

than in 2009 and their governance better scrutinized. Furthermore, taking into

account the Premier League’s latest media rights deal, it is questionable

whether abandoning FFP could in any way lead to a narrower gap between the rich

clubs and the rest.

[1] The definition of

net debt according to UEFA includes net borrowings (i.e. bank overdrafts and

loans, other loans and accounts payable to related parties less cash and cash

equivalents) and the net player transfer balance (i.e. the net of accounts

receivable and payable from player transfers) – see UEFA’s

eighth club licensing benchmarking report on European football, slide 125

[2] Oskar van Maren, “The Real

Madrid case: A State aid case (un)like any other?” (2015) Competition Law Review, Volume 11 Issue

1, pages 86-87.

[3] See for example, UEFA Club

Licensing Benchmarking Report Financial Year ending 2008, slide 4.

[4] Article 2 (2) of

both the 2012 and 2015 FFP

Regulations.

[5] 58-63 of the FFP

Regulations. Article 61 allows for an acceptable deviation of €5 million, i.e.

the maximum aggregate break-even deficit possible for a club to be deemed in

compliance with the break-even requirement.

[6] Markus Sass, “Long-term

Competitive Balance under UEFA Financial Fair Play Regulations” (2012), Working

Paper No. 5/2012.

[7] For an analysis of

FFP under EU competition law, see for example Stefan Szymanski, “Financial Fair Play

and the law Part III: Guest post by Professor Stephen Weatherill”, 14 May 2013, Soccernomics.

[8] UEFA Press release

of 12 January 2017, “European

club football’s financial turnaround”.

[9] Ibid.

[10] In fact, the

discussion on financial balance between football clubs has been a constant theme

for decades. Particularly the elaborated opinion of A.G. Lenz

in the Bosman case is worth reading in that regard (paras. 218-234).

[11] UEFA’s

eighth club licensing benchmarking report on European football, slide 74.

[12] Ibid, slide 75.

[13] Annex XII under A

(2)iii) of the 2015 FFP Regulations. The application deadline is the 31

December preceding the licence season in which the voluntary agreement would

come into force.

[14] Annex XII under B of

the 2015 FFP Regulations.

[15] FC Barcelona and

Real Madrid are expected to make €150m and €143m respectively, meaning that the

other clubs would receive an average of €55m.

[16] UEFA Press release of 12 January 2017, “European club football’s financial turnaround”.

[17] Once again, see the

opinion of A.G. Lenz

in the Bosman case (paras. 218-234).

[18] Threatening to put

in place a breakaway (European) league is a favoured method by some of the top

clubs. For example, during last week’s row it had with La Liga following the postponement of the Celta – Real Madrid game,

Real

Madrid held that the Spanish league is not very well organised and that they

are better off playing in a European Super League.