The tax

benefit scheme in the Hungarian sport sector decision of 9 November 2011 marked a turning point as

regards the Commission’s decisional practice in the field of State aid and

sport. Between this date and early 2014, the Commission reached a total of ten decisions

on State aid to sport infrastructure and opened four formal investigations into

alleged State aid to professional football clubs like Real Madrid

and Valencia CF.[1]

As a result of the experience gained from the decision making, it was decided

to include a Section on State aid to sport infrastructure in the 2014 General Block Exemption Regulation. Moreover, many people, including myself, held that

Commission scrutiny in this sector would serve to achieve better accountability

and transparency in sport governance.[2]

Yet, a recent report by

Transparency International (TI), published in October 2015, raises questions about the efficiency of State aid enforcement in

the sport sector. The report analyzes the results and effects of the Hungarian tax benefit scheme and

concludes that:

“(T)he sports

financing system suffers from transparency issues and corruption risks. (…) The

lack of transparency poses a serious risk of collusion between politics and

business which leads to opaque lobbying. This might be a reason for the

disproportionateness found in the distribution of the subsidies, which is most

apparent in the case of (football) and (the football club) Felcsút.”[3]

In other words, according to TI, selective economic

advantages from public resources are being granted to professional football

clubs, irrespective of the tax benefit scheme greenlighted by the Commission

or, in fact, because of the tax

benefit scheme.

One would expect TI’s report to be a wake-up call for

the Commission, triggering it, as “Guardian of the Treaties”, to re-investigate

Hungary’s tax benefit scheme without delay. Further incentives to scrutinize

the matter is provided by the Hungarian MEP Péter Niedermüller, who in November

2015 officially asked the Commission whether it intended to review its

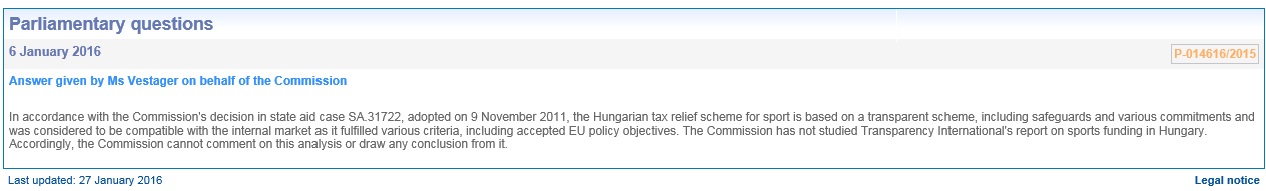

earlier decision to authorize the tax benefit scheme. The Commission’s answer,

seen here below, indicates that immediate action is not to be expected.

Not satisfied with this answer, Niedermüller replied that

even though the Commission had authorized the tax scheme in 2011, it does not

absolve it “from the obligation to proceed with the appropriate care thereafter

and to monitor whether the system is operating in accordance with the

objectives originally set”.

The overall aim of this two-part blog is to analyze

the rules and procedures surrounding the monitoring of previously authorized

aid schemes in the sports sector by the Commission. It will use the tax benefit scheme in the Hungarian sport

sector decision as a starting point, describing the objective and the

functioning of the aid scheme, as well as the conditions and obligations for

Hungary and the Commission attached to it. In continuation, basing myself on

the findings and conclusions drawn in the report, I will try to determine

whether the current practice in Hungary deviates from the original objectives

and conditions of the aid scheme, and what the consequences of such a deviation

could be. Do the State aid rules impose an obligation upon the Commission to

act and, if so, in what way? Furthermore, could the Hungarian case make one reconsider the usefulness of State aid

rules to achieve better accountability and transparency in sport in general?

The tax benefit

scheme in the Hungarian sport sector decision

A description of the

scheme

In April 2011, the Hungarian authorities notified the

Commission of their plans to introduce a tax benefit scheme with the aim of

developing the country’s sport sector.[4]

More specifically, via the scheme, they hoped to “increase the participation of

the general public in sport activities, by inter

alia, promoting mass sport events, training of the young generations as

well ensuring adequate sport infrastructure and equipment for the general

public”. Due to the existence of a market failure (i.e. a situation where

individual market investors do not invest even though this would be efficient

from a wider economic perspective), Hungary saw itself obligated to provide

public money to the sport sector in order to achieve the aforementioned objectives.[5]

Under the scheme, which will run until 30 June 2017,

corporations (operating in any sector that is subject to corporate tax) can

choose to donate money to sport organizations, both amateur and professional. Sport

organizations may use these resources to train the young generation, cover

personnel expenses and to construct/renovate sport infrastructure. The

donations would be deducted from the corporation’s taxable income and from

their tax liability.[6]

Hungary decided to focus the aid scheme on the five most popular team sports in

the country, i.e. football, basketball, ice hockey, water polo and handball. The

reasoning behind this choice is that the scheme would not only benefit the

sport organizations themselves, but also the sportsmen and sportswomen using

the facilities, as well as the general public interested in attending the

sporting events.[7] Sport

organizations wishing to receive donations have to elaborate a development

programme (DP), in which they outline the planned use of the donations. The DPs

are evaluated by the respective national sport governing bodies (SGBs), who

decide whether the sport organization is eligible for the donations. Once the

SGBs approve a DP, the sport organizations may approach corporations willing to

donate money to them.[8]

In the specific case of donations used for the

construction, renovation or maintenance of sport infrastructures, Hungary

notified the Commission that it had introduced a monitoring system that serves

to avoid any misuse of the donations or cross-subsidizations of other

activities of sport organizations. The so-called Controlling Authority (a

public entity falling directly under the Ministry of National Resources)

monitors compliance of donators and beneficiaries with the central price

benchmarking mechanism regarding rental and operation fees of the infrastructure,

introduced to limit the distortion of competition arising from the tax benefit

scheme.[9]

The Commission’s

decision

As stated above, the donations should be used to fund

the development of sport infrastructure, train the youth teams and cover personnel

expenses. The Commission agreed with Hungary that the training of youth teams

falls outside the scope of EU State aid rules, in line with the 2001 Commission

Decision Subventions

publiques aux clubs sportifs professionels. Donations used to cover personnel costs could be falling

under the General Block Exemption Regulation[10] or the de

minimis aid Regulation.[11]

Compliance with the two Regulations is a task for the Hungarian authorities.[12]

Consequently, and taking into account that amateur sport clubs are generally

not considered to be undertakings within the meaning of Article 107(1) TFEU, the

tax benefit scheme in the Hungarian sport

sector decision only covers aid for the infrastructures used by the

professional sport organizations.

Although the tax benefit scheme fulfilled the criteria

of Article 107(1), and thus constituted State aid, the Commission declared the

scheme compatible with EU law under Article 107(3)c) TFEU. Importantly, the

Commission held that the scheme was introduced in a sufficiently transparent

and proportionate manner, i.e. that the measure was well-designed to fulfil the

objective of developing the country’s sport sector.[13]

Moreover, the Commission acknowledged the special characteristics of sport and

held that the objective of the scheme is in line with the overall objectives of

sport as stipulated in Article 165 TFEU, namely that the EU “shall

contribute to the promotion of European sporting issues”, because the sport

sector “has enormous potential for bringing the citizens of Europe together,

reaching out to all, regardless of age or social origin”.[14]

It is worth mentioning that the Commission took a very

similar approach in its decisions on the other State aid measures granted for

sport infrastructure. It considers a sport infrastructure as embodying a

typical State responsibility for which the granting of State aid is a

well-defined objective of common interest.[15]

Finally, to ensure that the monitoring and

transparency obligations are carried out properly, the Commission requires

Hungary to submit an annual report to the Commission, containing inter alia, information on the total aid

amount allocated on the basis of this scheme, the sport infrastructure projects

funded, their aid intensities, their beneficiaries, the parameters applied for

benchmarking prices, the rents effectively paid by the professional sport

organizations, as well as a description on the benefits provided to the general

public and on the multifunctional usage of the infrastructures.[16]

There is no requirement to publish this annual report. Therefore, assessing

whether the information provided by Hungary to the Commission is in line with

the actual practice in the country is currently extremely difficult.

Transparency

International report, “Corruption Risks in Hungarian Sports Financing”

The tax benefit

scheme in the Hungarian sport sector decision looked like a blue print for

the way in which public authorities could grant State aid to the sport sector:

It was aimed at a wide scope of recipients and the general public would benefit

as well, transparency was guaranteed, monitoring and compliance mechanisms were

introduced and, last but not least, it was notified in advance to the European

Commission.

Lack of transparency

However, TI’s report shows that, four years after the

scheme was launched, little remains of all those good intentions. To start

with, TI claims that Hungary’s objective was not to increase the participation

of the general public in sport activities, but simply to make Hungarian

football clubs “excel at the European and international levels”.[17]

TI’s primary finding is that there is a flagrant lack of transparency on every

level regarding the scheme. Most of the data collected in the report was

obtained by TI through freedom of information requests.[18]

The first flaw in the scheme is that under Hungarian

national laws and regulations, there is no obligation to disclose the identity

of the donating corporations. Consequently, even though the SGBs keep count of

which clubs are entitled to receive donations and how much they actually

received, many questions remain on how the money is distributed in practice.

TI also questions the integrity of the clubs’

eligibility process. The Hungarian SGBs, who are in charge of selecting the

clubs worthy of receiving donations, are to a large extent run by people with

close ties to the Hungarian Government.[19]

Moreover, for the selection process, the SBGs do not need to provide a

reasoning behind the decision to choose or not to choose a club worthy of

donations. As TI states, the tax benefit scheme poses a serious threat to

transparency and accountability, and can lead to illicit lobbying and backroom

deals between politicians, businessmen and clubs.

Disproportionate

distribution of beneficiaries

The advantage of using a general tax scheme as a State aid measure is

that it leads to many different beneficiaries and is therefore considered as

one of the least distortive type of state intervention.[20] However,

the functioning of this particular tax benefit scheme creates the exact

opposite result a few clubs are clearly favored. According to the report, the

subsidies from the tax scheme totaled €649 million in four years. An amount of

€240 million was specifically designated for football clubs, 37% of the total

amount. Of all the money donated to football, 28% (or €68 million) went specifically

to 13 football clubs, who, perhaps unsurprisingly, all play in Hungary’s

highest football league.[21] Of

these 13 football clubs, Puskás Akadémia FC received by far the highest amount,

no less than €30 million. Puskás Akadémia FC plays in Hungary’s top division,

but also functions as the youth team of Videoton FC, one of Hungary’s biggest

and most successful clubs. Interestingly enough, Puskás Akadémia FC was founded in 2007 by the current Hungarian Prime

Minister Viktor Orban.

Unnecessary

construction of new sport infrastructure?

The Hungarian authorities expressed the need in 2011

for adequate sport infrastructure facilities. Due to a market failure, it was

necessary for the State to step in and provide the necessary funds, albeit by

means of a tax benefit scheme. The Commission agreed with Hungary that there is

a lack of investments in sport infrastructure and that using public money to do

so is an objective of common interest.[22]

The TI report indicates that especially the Hungarian football stadiums have

undergone significant upgrades since 2011, but at the same time questions the

necessity to use public funds for these upgrades. Hungarian professional

football has not been attracting more people to stadiums since 2011. The

country’s highest division averaged only 4,897 spectators per game for the

2014/15 season, 624 less than in the previous year.[23]

An example of potential unnecessary construction of sport infrastructure is the

“Nagyerdei” stadium, opened in 2014, in

the city of Debrecen. The stadium, that can hold over 20,000 spectators, cost €40 million

to construct. However, with a match average of 3,400,[24]

one wonders whether the construction of this stadium was an objective of common

interest, or whether there was another, hidden, agenda. Referring to the well-reported,

including by the European Commission, close relationships between Hungary’s businesses and

its political elite, TI points to the realistic possibility that the

construction and renovation of (football) stadiums through public procurement

procedures, was simply a way to for contractors to “finance the economic orbit

of influential politicians in return for all manners of political and financial

favours”.[25]

Interim conclusion

TI’s report clearly shows that there is a huge

discrepancy between Hungary’s intention to devise a tax benefit scheme

benefitting to the entire sport sector, as notified to the Commission in 2011,

and the actual operation of the scheme. The necessity for new and renovated football

infrastructure appears superfluous and the tax benefit scheme itself proved to

be more beneficial for some clubs, particularly Puskás Akadémia FC. Furthermore,

the Commission decision declaring the tax benefit scheme compatible with EU law

highlighted the transparency of the scheme and acclaimed its monitoring

mechanisms. More than four years on, it can be concluded that the scheme is far

from transparent and questions can be raised on the independence and

functioning of the monitoring mechanisms. Assuming that the Commission receives

annual reports by the Hungarian authorities on the tax benefit scheme, why has

it not undertaken any action? Is it simply a matter of unwillingness or could

the answer be found in EU State aid law and its procedural rules itself? The

next part of this blog will analyze the rules and procedures surrounding the

monitoring of previously authorized aid schemes by the Commission, and

determine whether Commission action can be expected.

[1] An explanation on

why the public financing of sports infrastructure and professional sports clubs

only started to attract State aid scrutiny in recent years can be read in: Ben

Van Rompuy and Oskar van Maren, “EU

Control of State Aid to Professional Sport: Why Now?” Forthcoming in: “The Legacy of Bosman. Revisiting the relationship

between EU law and sport”, T.M.C. Asser

Press, 2016.

[2] See for example

Oskar van Maren, “EU State Aid Law and

Professional Football: A threat or a Blessing?”, European State Aid Law Quarterly,

Volume 15 1/2016, pages 31-46.

[3] Transparency

International, “Corruption Risks in Hungarian Sports Financing”, page 41.

[4] Commission Decision

of 9 November 2011, SA.31722 – Hungary - Supporting

the Hungarian sport sector via tax benefit scheme, paras 2-3.

[5] Ibid., paras 88-90.

[6] Ibid., paras 15-16.

[7] Ibid., paras 28-34.

[8] Transparency

International report of 22 October 2015, “Corruption Risks in Hungarian Sports

Financing”, page 31.

[9] Commission Decision

SA.31722, paras 37-39.

[10] The GBER applicable

at the time the decision was taken was Commission Regulation No800/2008 of 6

August 2008.

[11] Commission

Decision SA.31722, para 10.

[12] Ibid., para 64.

[13] Ibid., paras 95-98.

[14] Ibid., paras 86-87.

[15] See for example

Commission Decision of 20 March 2013, SA.35135 Multifunktionsarena der Stadt Erfurt, para 14.

[16] Commission Decision

SA.31722, para 57.

[17] Transparency

International report, page 29.

[18] Ibid., page 31.

[19] Ibid., page 32. TI points out that the chairman

of the Hungarian FA is CEO of the country’s biggest commercial bank and close

to the Government.

[20] Commission Decision

SA.31722, para 20.

[21] The TI report

actually mentions the clubs as well as their youth academia. The 13 clubs are:

Puskás Akadémia FC (aka Felcsút FC, the youth team of Videoton FC);

Ferencváros; Újpest FC; Vasas SC; Szolnoki MÁV FC; Debreceni VSC; Diósgyőri

VTK; Zalaegerszegi TE; OVI-FOCI; Illés Sport Alapítvány; Budapest Honvéd FC;

Balmazújvárosi FC and; Békéscsaba 1912 Előre.

[22] Commission

Decision SA.31722, paras 91-93.

[23]

Transparency International report, page 38.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid., page 42.