On

the first of May 2015, the Spanish Government finally signed the Royal Decree

allowing the joint selling of the media rights of the Spanish top two football

leagues. The Minister for Sport stated that the Decree will allow clubs to “pay

their debts with the social security and the tax authorities and will enable

the Spanish teams to compete with the biggest European Leagues in terms of

revenues from the sale of media rights”.[1]Although

the signing of the Royal Decree was supposed to close a very long debate and

discussion between the relevant stakeholders, its aftermath shows that the Telenovela is not entirely over.

This

blog post will first provide the background story to the selling of media rights

in Spain. It will, thereafter, analyse the main points of the Royal Decree and outline

how the system will work in practice. Finally, the blog will shortly address

the current frictions between the Spanish League (LFP) and the Spanish football

federation (RFEF).

I. The road

to the royal decree

The old individual selling system

The

individual selling model of media rights in Spain was adopted in the 1997/1998

season. The Spanish individualized marketing system required that the TV

operators and the clubs sign individual agreements over the media rights for La Liga games. Obviously, not all the

agreements were born equals. The two biggest clubs in Spain, Real Madrid and FC

Barcelona, were soon deriving much more revenue from TV rights as the other

clubs. Hence, it is not surprising that latter have been asking for a bigger

share of the TV rights revenues since then. For the 2014/15 season, for

example, Barcelona and Madrid earned 140 million € each, whereas Córdoba, Eibar

and Deportivo la Coruña have only earned 17.5 million €. Even the last winner of

La Liga (Atlético de Madrid) has received

only 45 million € (3.1 times less than Barcelona and Madrid). Meanwhile, the overall

sum paid by the operators to all the teams (MEDIAPRO Agency and PRISA Media

Group) reached 742.5 million €/year for a three-year deal (2012/13 to 2014/15).[2]

Due

to the delay in approving the Royal Decree, some clubs (such as Barcelona) decided

to sign an individual contract with a TV operator for the 2015/16 season. Consequently,

it is unlikely that La Liga will be

able to collectively sell its media rights for the next season. However, the

new system should be in place for the 2016/17 season.

Disagreements prior to the Royal Decree

The

negotiating process prior to signing the Royal Decree involved three main

stakeholders: the Spanish Government (CSD –High Sports Council- and the

Minister for Sport), the RFEF and, obviously, the LFP. The most difficult hurdle

to overcome was the RFEF’s demand of a

non-negotiable 2% share of the broadcasting revenues. Both the CSD and the LFP refused

to budge and considered that the RFEF should not get more than 1%. The

negotiations were especially tense as a consequence of a personal feud between

the presidents of the main bodies involved.

Why a Royal Decree?

Notwithstanding

the RFEF’s outspoken disapproval, the Royal Decree 5/2015 was adopted by the

Council of Ministers on 30 April 2015 and was published in the Official Journal

on the following day. In principle, a Royal Decree is only used for

extraordinary and urgent matters and the Spanish Parliament must consolidate it

in a law 30 days after its approval, which was done, last week. Nevertheless,

one may question whether this was truly a matter of urgency requiring the introduction

of a Royal decree. According to the explanatory

memorandum of the Royal Decree it

is justified on the basis of the public interest in securing a new system to

commercialize the media rights. The justifications included in the Decree read

as follows:

“Concerning the media rights of

professional football competitions, three reasons justify the need for an

urgent response by the Government: first, the undisputed social relevance of

professional sport, second, the repeated and unanimous demands to intervene

from all parties involved and, finally, the need to promote competition in the

market for the ‘pay-per-view’ television.”[3]

II. The new LFP’s media rights collective

selling system

The

LFP’s media rights remain owned by the

clubs. However, the football clubs are obliged to assign the right to

commercialize them to the organizing bodies of the competition, i.e. the LFP

(first and second division) and the RFEF (the cups).[4]

The conditions for the joint selling of

the media rights

In

accordance with article 4 of the Royal Decree, the organising bodies will

commercialize the media rights on an exclusive or non-exclusive basis. Moreover, the procedure must be fair and

equitable. The LFP and the RFEF will define the different packages

commercialized in line with Article 4(4) of the Royal Decree. These conditions will be attached by the

organizing body into categories (‘packages’), depending whether it is on an

exclusive basis or not, the time of the game and the duration (maximum 3

years), in accordance with the Article 4(4). The structure of the packages will

be set out when the collective selling takes place.

The

specific distribution key of the revenues derived from the collective selling

is enshrined in Article 5: 90% of the revenues will go to the first division

clubs, and 10% to the second division clubs.

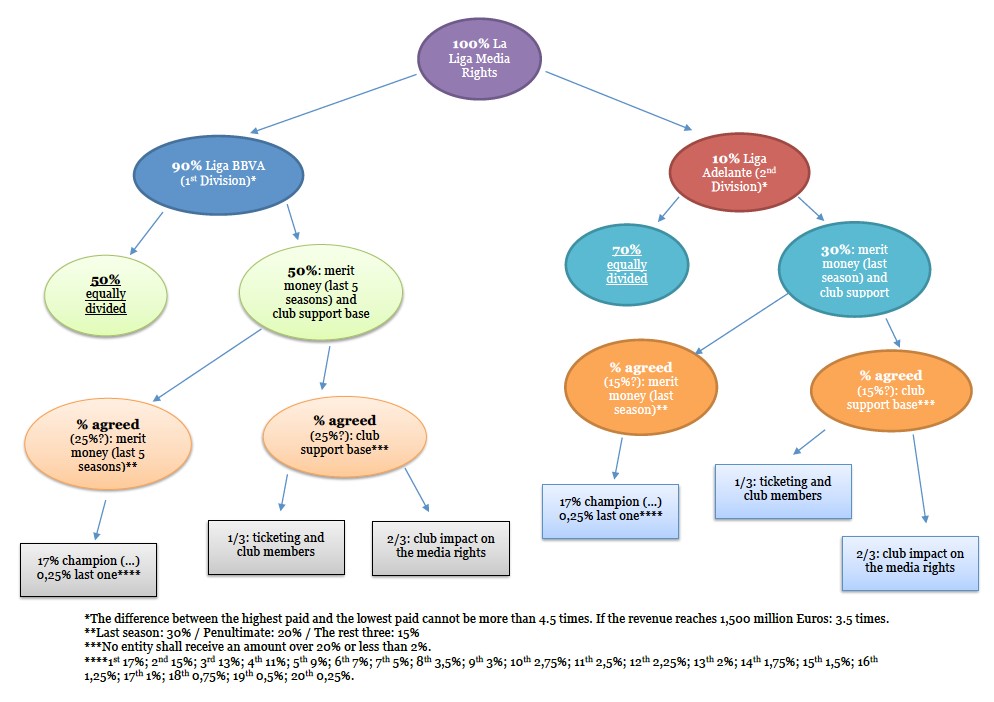

Graph: Distribution of the money

regarding the media rights of the first and second division:

Payments by the clubs after the distribution

of revenue: The overdue debts to the Public Revenue and the indirect solidarity

contributions.

After

receiving their share of revenue from the media rights, the clubs must first

cover their overdue debts with the Spanish tax authorities. Indeed, Article

6(2) holds that “(t)he payment of overdue and payable debts owed to the

‘State Agency Tax Administration’ and the ‘General Treasury of the Social

Security’ shall be considered on a preferential basis”. No club will be able to

carry out the indirect solidarity payments foreseen by Article 6(1), if they do

not reimburse their outstanding liabilities with the public authorities.

It is a well-known fact that

Spanish football clubs have accumulated large amounts of debts over recent

years. Indeed, at the end of the year 2013, the debt of the Spanish football

amounted to 3.600 million € in total, with “around 700 million” to

the public authorities. The Royal

Decree is also aimed at tackling this longstanding debt “addiction” of many Spanish

football clubs.

Furthermore,

in accordance with article 6(1) of the Decree, the clubs will have to make

solidarity contributions to specific funds and Institutions promoting football

and sport. These contributions will only be made after the obligatory

contributions to the tax authorities have been paid. The five contributions include:

3.5% of the broadcasting revenues will be used to

create a ‘Compensation Fund’ in order to assist relegated clubs from the first

Division to the second and from the second division to the third division (in

Spain known as the second division “B”). Out of the Compensation Fund, 90% will

flow to the relegated clubs from the first Division and 10% to the relegated

clubs from the second Division.

1% of the broadcasting revenues will go to the LFP

for the purpose of promoting the League on the domestic and international

market.

1% of the broadcasting revenues will go to the RFEF

as a solidarity contribution to develop amateur football[5].

Up to 1% of the broadcasting revenues will go to the Consejo Superior de Deportes (CSD), a

Spanish Governmental body encouraging the development of sport in Spain. The

goal of this contribution is to finance the social protection of high-level athletes

(not just football players).

A further 0,5% of the broadcasting revenues will go to

the CSD, and shall be distributed in the following way:

Aid to female

football clubs participating in the Women’s First Division, covering social

security contributions.

Aid to football

clubs participating in the Second Division “B”, in order to pay social security

contributions.

Aid to

associations or unions of players (‘AFE’),

referees, coaches and trainers.

The Spanish cup and Supercup

revenue-sharing criteria

The

packages will be made according to the criteria similar to those applicable to

the LFP’s media rights. The revenue generated by the RFEF’s competitions will

be shared as follows (Article 8):

90% will be directly allocated to the LFP teams (first

and second division). This money will be distributed to these clubs using similar

criteria as for LFP Competitions. The revenue share depends on the results obtained

by the teams in the cup. The distribution envisaged foresees 22%, for the winner;

16%, for the runner-up; 9%, for the semi-finalists; 6%, for the

quarter-finalists; and 2,5%, for the clubs who got knocked-out the round of the

last 16.

10% will be used for the promotion of lower (semi)

professional football and amateur football, that is to say, for clubs who play

in the cup but are not in first or second division.

III. The Problem with the Decree: RFEF

and AFE’s Opposition

The

main beneficiaries, i.e. the clubs, are quite exultant after the publication of

the Royal Decree. Nonetheless, two bodies believe that they are the principal losers

of the distribution model adopted, namely the RFEF and AFE (Spanish Professional Footballer's

Association). In fact, the RFEF and AFE’s discontent is such that they have threatened

to organize a strike paralysing the last few games of the current season,

should the Decree not be renegotiated.

RFEF

The

RFEF wanted 2% of

the total revenue for itself, but the Decree allocated to the RFEF only 1% of

the total. , As discussed above, this share will be paid indirectly by the club

as outlined in Article 6(1). This implies that the federation will get paid

only once, and if, the clubs have serviced their overdue debts with the public

authorities.

In

addition to this, the Federation did not obtain any compensation for women’s

football or (semi) professional football in lower divisions. The competence for

supporting women’s football and lower professional football rests with the CSD even

though it is the RFEF that is in charge of the organisation of the competitions.

In other words the RFEF has no control over the money flowing into the

competitions it is responsible for.

AFE

The

frustration expressed by AFE

(Professional Footballer's Association) is also understandable. The players

have not obtained a fixed share of the broadcasting revenues, as is the case in

England (1.5%) or France (1.09%). Nevertheless, according to the Royal Decree, AFE will

receive from the CSD a contribution of “up to 0.5%” (Article 6(1)(e), par. 3). Moreover,

the players’ representatives claim they were unjustifiably excluded from the negotiations.

Without the ability of partaking to the negotiations, they were unable to secure

higher guarantees for the players regarding the payment of the salaries in the lower

divisions of Spanish football. Given that many players do not receive their

salaries on time in the lower Spanish divisions, this money would have been a potential

solution to a chronicle problem.

The strike

In

return, AFE (supported by elite players like Casillas, Xavi, Piqué or Ramos) threatened with a strike. For its part, RFEF suspended all the Spanish

football competitions. In response to these moves, the LFP lodged a case

against AFE in the Spanish Courts, requesting the

suspension of the strike and the recognition of its illegality as it would lack

a legitimate ground and would violate the existing collective bargaining

agreement.

The

Audiencia Nacional (the National High

Court in Spain) decided on

14 May in a preliminary decision to suspend the strike. This decision ensured that

the last two games of the season and the final of the Copa del Rey will be played. The case is still pending and awaits a

decision on the merits. The hearing will be held on 17 June. The parties have already commenced negotiations in order to reach an agreement before the hearing. But,

given that the Royal Decree has been ratified by the Parliament, very few

substantial changes to the system put in place by the Decree can be made. Thus,

only minor peripheral adjustments are to be expected.

Conclusion

In

my opinion, there are two key aspects that must be kept in mind. First, the

duty to pay overdue debts to the public Authorities. This mandatory requirement

cannot be found in any other countries and is clearly linked with the specific

problems that exist in Spanish football with regard to the clubs’ indebtedness

and the enmeshment of local politicians in their management. On the other hand,

the other key change introduced by the Royal Decree will be that La Liga will be in a position to

negotiate a much hoped for gigantic TV deal with the broadcasters. A deal,

which will not exclusively benefit Real Madrid and FC Barcelona. The economic

gap between these two teams and the rest of the pack was growing bigger and

bigger over the last years. With the new system in place, this gap is poised to

be reduced. Nevertheless, the distribution method still heavily favours the status-quo. The traditionally large

clubs are rewarded for having a large number of supporters, and for their past

performances. Hence, it is still virtually impossible for a smaller Spanish clubs

to become, over a short time span, one of the top-earning clubs in La Liga.

[1] IUSPORT: “Aprobado el

Real Decreto-Ley de los derechos audiovisuales del fútbol”

http://iusport.com/not/6713/aprobado-el-real-decreto-ley-de-los-derechos-audiovisuales-del-futbol/

[2] MARCA, “Así será

el reparto del dinero televisivo”, available at http://www.marca.com/2015/05/01/futbol/1430467483.html

[3] RD

5/2015, Explanatory Memorandum.

[4]

Article 2 RD 5/2015.

[5] This percentage may be expanded by agreement