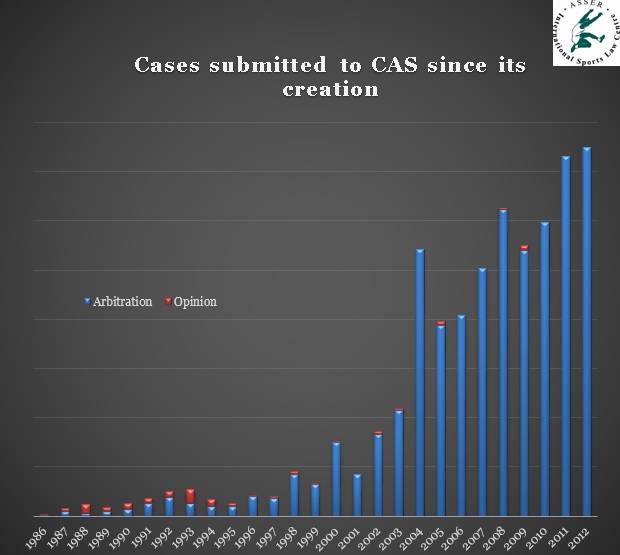

Graph 1: Number of Cases submitted to CAS (CAS Satistics)

The Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) is a fairly recent construct. It was created in 1984 under

the patronage of IOC’s former president Juan Antonio Samarranch. However, as is evident from Graph 1, it gained

prominence only at the turn of the century and reached the symbolic 100

cases/year bar only in 2003. This recent boom of the CAS docket is mainly due

to the adoption of the WADA code and the introduction thereafter of binding

arbitration clauses in the statutes and regulations of Sports Governing Bodies.

Nowadays, CAS is dealing with a caseload of more than 350 cases/year, which is

still growing constantly. From 2008 onwards CAS started even to experience pending

cases, as it was not able anymore to process all the cases submitted in one

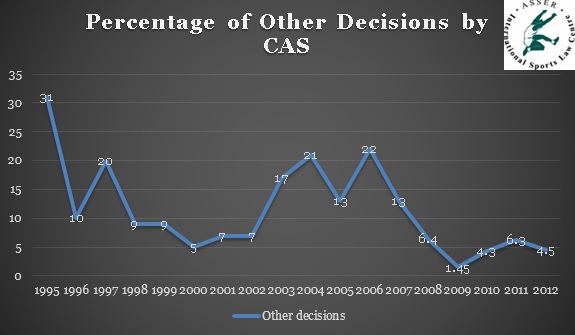

calendar year (Graph 2). The steep fall of “other decisions” (Graph 3), a proxy

for decisions (mostly on procedural matters) not involving an award, might indicate that

the litigants and their lawyers have become more proficient in CAS procedure. Finally,

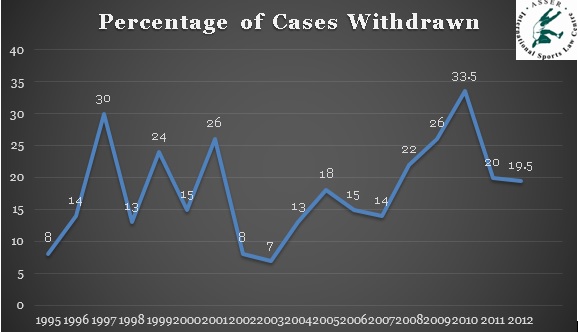

the number of cases withdrawn (Graph 4) has been varying a lot, without it

being possible to pin down any definitive cause explaining those variations. It

is, however, notable that more than 2/3 of the cases give way to an award.

Graph 2: Percentage of the cases resulting in an Award/Opinion vs.

Percentage of pending cases (Data CAS Statistics)

Graph 3: Percentage of

Procedures terminated by a CAS decision other than an award (Data CAS

statistics)

Graph 4: Percentage of

Cases withdrawn before a decision by the CAS (Data CAS statistics)

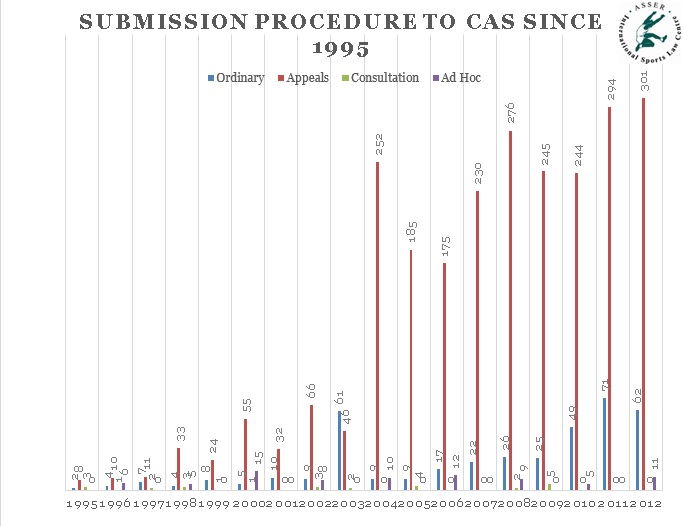

The breakdown of the way cases were submitted to CAS (Graph 5)

highlights very well the paramount role played by the 1994 reform process triggered by the Gundel ruling of the Swiss Federal Tribunal in

1993. Indeed, it is this reform process which enabled the final recognition

of CAS as an independent tribunal by the Swiss Federal Tribunal, a move

necessary to ensure the legitimacy of its awards. But, it is also the process

through which the appeal procedure of CAS got solidified and became highly valuable in the eyes of Sports

Governing Bodies. In light of the Bosman case and the perceived need for a

global anti-doping Court, CAS became both a recourse to protect the sporting

autonomy and a mean to ensure a harmonized anti-doping playing field. Thus it

is not surprising that with the entry into force of the first World Anti-Doping

Code in 2004 a huge jump in the number of CAS cases under the appeal procedure

can be observed (Graph 5), passing from 46 in 2003 to 252 in 2004 and growing

to 301 in 2012. In the meantime, the ordinary procedure cases have been stable

with 61 cases in 2003 and 62 in 2012. CAS’s success is largely the success of

the appeal procedure, but this appeal procedure seems potentially threatened after the recent Pechstein decision of the

Landesgericht München. Furthermore, since 1996 ad hoc CAS proceedings have been introduced. At first only for Olympic games

(every two-year) and more recently for other international

competitions. However, the caseload of the ad-hoc tribunals remains modest, the peak

was reached at the Sydney Olympic in 2000 with 15 cases, since then Ad-hoc

tribunals have been in the shadow of the prominent place taken by the Appeal

Procedure.

Graph 5: Types of procedure (Ordinary

Procedure, Appeal Procedure, Consultation Procedure and Ad-Hoc Procedure) under

which cases were submitted to CAS since 1995. (Data CAS statistics)

Finally, our last Graph 6 shows that the boom of the number of CAS

awards has quite logically triggered a steep rise in the number of appeals

against those awards submitted to the Swiss Federal Tribunal. Indeed, starting from

one or two decisions per year in the early 2000s, the Swiss Federal Tribunal is

now adopting more than 15 rulings per year on appeal of CAS awards. However,

very few of these decisions have overruled CAS awards, moreover once an award

is overruled it is usually sent back to CAS to decide de novo on the case, thus giving it the opportunity to correct any

procedural mistake leading to the annulment of the first award. This appeal

procedure is therefore rather a mock procedure; an appellant has very little

chances to succeed. In fact, it is only recently that in a case concerning a

CAS award (the Matuzalem

case),

the Swiss Federal Tribunal considered, for the first time, an arbitral award as

contradicting Swiss material public policy. The route to the Swiss Federal

Tribunal might be the most obvious to any athlete wishing to contest a CAS

award, but it is definitely a very difficult (and costly) one, leaving very few

reasons to hope for a final twist.

Graph 6: Number of

Decisions of the Swiss Federal Court in Appeal against CAS awards. (Data ASSER)

This report on the Court of Arbitration for Sport was aimed at fleshing

out the intuition of sports lawyers on the importance taken by CAS in

contemporary sports law practice with some “hard” data illustrating both the

temporal and quantitative shifts of the CAS relevance. The rise of the CAS

needed to be statistically deconstructed and analysed in order to fully grasp

the role it plays in the governance of sports. Furthermore, its interaction

with state courts, and in particular with the Swiss Federal Tribunal, deserves

close scrutiny. In many instances the Swiss Federal Tribunal is the sole forum

of review for CAS awards. This is particularly true for athletes, which have

usually been forced, in one way or another, to submit to arbitration. Thus, the

debates around the legitimacy and role of CAS in sports governance can only

gain from an enhanced knowledge of the empirical reality underlying the Court

of Arbitration for sport.

Indicative Bibliography on CAS:

A. Rigozzi,

Arbitrage International en matière de sport

A. Rigozzi,

Challenging Awards of the Court of Arbitration for Sport

G. Kaufmann-Kohler

Arbitration at the Olympics – Issues of Fast-Track Dispute

Resolution and Sports Law

M. Maisonneuve,

Arbitrage des litiges sportifs

I.S. Blackshaw, J. Soek, R. Siekmann

(Eds.), The Court of Arbitration for Sport 1984–2004

R. H. McLaren, Twenty-Five Years

of the Court of Arbitration for Sport: A Look in the Rear-View Mirror

D. Yi, Turning

Medals into Metal: Evaluating the Court of Arbitration for Sport as an

International Tribunal

The CAS Database of

awards

The CAS

Bulletin

The Swiss Federal

tribunal database

(French and German)