Editor’s note:

Thomas Terraz is a fourth year LL.B. candidate at the International and

European Law programme at The Hague University of Applied Sciences with a specialisation

in European Law. Currently he is pursuing an internship at the T.M.C. Asser

Institute with a focus on International and European Sports Law.

1. Introduction

The UCI may soon have to navigate treacherous legal

waters after being the subject of two competition law based complaints (see here and here) to the European Commission in less than a month over rule changes and

decisions made over the past year. One of these complaints stems from Velon, a private

limited company owned by 11 out of the

18 World Tour Teams,[1]

and the other comes from the Lega del Ciclismo Professionistico, an entity

based in Italy representing an amalgamation of stakeholders in Italian

professional cycling. While each of the complaints differ on the actual

substance, the essence is the same: both are challenging the way the UCI exercises

its regulatory power over cycling because of a growing sense

that the UCI is impeding the development of cycling as a sport. Albeit in different ways: Velon sees the UCI infringing on its ability

to introduce new race structures and technologies; the Lega del Ciclismo

Professionistico believes the UCI is cutting opportunities for

semi-professional cycling teams, the middle ground between the World Tour Teams

and the amateur teams.

While some of the details remain vague, this blog

will aim to unpack part of the claims made by Velon in light of previous case

law from both the European Commission and the Court of Justice of the European

Union (CJEU) to give a preliminary overview of the main legal issues at stake

and some of the potential outcomes of the complaint. First, it will be crucial

to understand just who/what Velon is before analyzing the substance of Velon’s

complaint.

2. Who / What is Velon?

From

an outsider’s point of view, the answer to this question is not so obvious as

it may seem. Velon itself is owned by 11 World Tour Teams, which is the pinnacle

of the UCI’s men’s team classification. In other words, Velon represents more

than half of the largest team stakeholders in road cycling.[2] However, Velon does not

just simply advocate for these teams’ interests, but it engages in its own

economic activities, which can be categorized into two types. First, it has been

the organizer of a new series of races called the Hammer Series (or as the UCI

would prefer, simply Hammer) where instead of having individual cyclists

(competing on behalf of a team) placing individually in a stage of a race, the

entire team is classified through a points-based system. The point of this

format is ‘crowning the best team in professional cycling’.

Velon

also created a ‘digital content and live data platform’ through VelonLive via a

partnership with EY, which was first

made public in May of this year. VelonLive essentially collects data from road

cycling races in order to give spectators more insight into the race. For

example, it collects ‘real-time biometric rider data’, including heart rate, power and cadence data from

specific riders in a race to on bike cameras and cameras in team

cars. The aim is to try to bring the race closer to the spectator by offering

more data and new ways to see and understand the race. Major race organizers,

like the Giro D’Italia and the Tour of Flanders have jumped on these new race

visualization technologies and used VelonLive this year in their respective

races.

So

not only does Velon act as a representative of a large group of first-rate road

cycling teams, but it also organizes races and is working to develop innovative

ways for cycling fans to experience road cycling races.

3. The Complaint

Velon,

through a press release on their website, announced that it

had launched a formal complaint against the UCI to the European Commission on 20

September, 2019 to which it added an ‘Addendum to the Complaint’ on 8 November, 2019.

While these press releases and accompanied ‘context notes’ are rather bare in

explaining the factual background to the complaint, it is still enough to

extract the essence of what is being alleged. At its core, Velon is making a three-pronged

complaint against the UCI: first, that the UCI acted in a way that has

‘hampered the development of the Series’ (Hammer Series); secondly, that the

UCI is discriminating against women’s cycling by denying the approval of a

women’s race that would accompany the already existing men’s race in Hammer

Stavanger; lastly, that the amendments to the UCI’s Technical Regulations effectively

take away Velon and other race organizers’ control over live race data technologies

and were adopted without sufficiently consulting stakeholders. Concerning the last complaint, Velon

seems to be referring to certain amendments from 15 February, 2019 made to the equipment regulations Article 1.3.024ter.

The changes essentially introduced a pre-authorization scheme

for ‘onboard technology equipment’ in which the UCI or an event organizer with the

UCI’s consent must give prior authorization for ‘any intended use by a team or

rider’ of such equipment. However, given both the scarce details and length

restraints, this

blog concentrates on the on the first two elements of the complaint, which are

further dissected here.

Velon

alleges that the UCI acted to prevent the organization of Hammer races into a series

and threatened to not register the men’s Hammer races in the 2020 calendar if Velon

proceeded to do so. As of 11 November, 2019, the three men’s Hammer

races are still listed in the 2020 calendar, while the women’s

Hammer Stavanger race is not listed, since it was rejected by the UCI. Velon also claims

that the UCI did not give any reasons for its opposition to the series and that

it ‘hampered’ the overall development of the series. Further details are rather

murky; however, it is essential to point out that the UCI, like many other

SGBs, employs a pre-authorization scheme[3] for cycling events, and it

prohibits both teams and individual cyclists (of all levels) in participating

in non-authorized third-party events under the threat of sanctions. Individuals

may face a one-month suspension and a fine of 50 to 100 CHF.[4] Such an event

pre-authorization scheme has been the focal point of two major EU sports

competition law cases: the CJEU’s decision in MOTOE and the Commission’s decision concerning the ISU’s

eligibility rules. It is likely that if the Commission takes on this case, it

will closely scrutinize the UCI’s pre-authorization scheme and its actual

application, including the accompanied sanctions. From the outset, it is

critical to bear in mind that the CJEU has held that rules of sport governing

bodies may escape the prohibitions under Article 101 TFEU if ‘the consequential effects restrictive of

competition are inherent in the pursuit of those objectives (Wouters

and Others, paragraph 97) and are proportionate to them’.[5] On the other hand, a

dominant undertaking may justify its actions under Article 102 TFEU if it can

demonstrate ‘that its conduct is objectively necessary or by demonstrating that

its conduct produces substantial efficiencies which outweigh any

anti-competitive effects on consumers’.[6]

As

a preliminary note, it should be stated that if the Commission decides to pursue

the case under Article 102 TFEU, it will not be hard pressed to find the UCI and

its respective national federations collectively dominant[7] in the relevant market.[8]

The relevant market regarding the Hammer races will most likely be confined to

the organization and commercial exploitation of international road cycling

races on the worldwide market.[9]

Even though the Professional Cycling Council (PCC) adopts the UCI WorldTour

calendar, Velon could still contend that the UCI exerts control over its

adoption given the composition of the PCC.[10]

4. Analysis of the ‘hampered’ Series and alleged discrimination

against women’s cycling

4.1.MOTOE

In

MOTOE, ELPA, a Greek motorsport

organization, was given the regulatory power through a national law to approve

or deny motorsport events in Greece, while also organizing and commercially

exploiting such events itself.[11] MOTOE challenged the

national law giving ELPA this power after one of its events was not approved. The

CJEU ruled that the dual role of ELPA as both a regulator and commercial

exploiter was contrary to competition law because it had not given an ‘equality

of opportunity’ ‘between the various economic operators’.[12] AG Kokott’s Opinion goes

further and describes a ‘conflict of interest’ in which sport governing bodies are

placed if they are both the gatekeeper and promoter of sport events.[13] A similar situation in

the Commission’s FIA case even resulted in the complete separation of FIA’s

‘commercial and regulatory functions’ in order to cease its breach of EU

competition law.[14]

Unlike

ELPA, the UCI is not given the power to regulate the events included in its

calendar by an act of a state or public body. Nonetheless, it still wields an

immense power over the regulation and approval of events in road cycling deriving

from its position as the world’s

cycling governing body. The UCI also benefits considerably from the

registration of events in its calendar, a fact that is quickly verified by

having a glance at its yearly financial report,[15] which demonstrates the

extent to which it is dependent on revenues connected to its sanctioned events.

The UCI can only justify charging fees for events if there is the existence of

an official closed calendar of events. Additionally, the UCI itself is an event

organizer since it arranges the annual UCI Road World Championships. Therefore,

it is very likely that the UCI may be faced with a ‘conflict of interest’ because

it holds the keys to its events calendar while having an apparent financial stake

in the approval of events.

At this

point, it is also helpful to examine the Commission’s decision in the ISU case which

delves in depth on the compatibility of event pre-authorization schemes with EU

law.

4.2.The Commission’s ISU

Decision

The ISU case concerned two Dutch speed skaters who

challenged the ISU eligibility rules precluding them from participating in

non-ISU authorized events, subject to a potential lifetime ban (the ban was

amended during the proceedings to allow greater flexibility on the sanction but

was still found to be contrary to EU law). The concerned skaters wished to participate

in IceDerby’s events. IceDerby is an ice-skating events organizer who aimed to

create a new race format that would introduce ‘a new type of skating events on

a different size track than the ISU recognized track’.[16] This

very much echoes some of the fact pattern of the present case in which Hammer

seeks to introduce a new road cycling race format. The Commission found that

the severity of the sanctions in case of a breach of the ISU’s eligibility

rules inherently aimed ‘at preventing athletes from participating in events not

authorised by the ISU, resulting in the foreclosure of competing event

organizers’.[17] In the end, the case

largely turned on whether the ISU’s eligibility rules pursued legitimate

objectives and whether they were inherent and proportionate to its aims. The

Commission identified that ‘the integrity of the sport, the protection of the

athletes’ health and safety and the organisation and proper conduct of sport’

could be considered legitimate objectives but that the ISU’s eligibility rules

did not actually pursue any of these objectives.[18] Moreover,

the Commission found that the financial and economic interests of the ISU could

not be considered legitimate objectives.[19]

In Velon’s complaint, as in the ISU case, there are

two connected, yet separate elements that the Commission will most likely have

to analyze: (a) the prohibition of participating in non-approved events and the

relevant sanctioning framework and (b) the UCI’s events approval process (the pre-authorization

scheme). Concerning the former, Pat McQuaid, the former UCI president explained

the aim of the rules banning participation in non-approved events in a letter to USA

Cycling back in 2013. He explained that it ‘allows for a

federative structure’, ‘which is inherent in organised sport and which is

essential to being a part of the Olympic movement’. The Commission dismissed

this notion in the ISU case when it pointed out that there are several sport

federations that do not have an ‘ex-ante control

system’ that effectively precludes athletes from participating in third party

events.[20] Nevertheless,

this stated objective may still fall under the organization and proper function

of sport, which was deemed a legitimate objective by the Commission.

However, the issue remains as to whether the UCI’s pre-authorization

scheme, the latter element identified above, pursues legitimate objectives

while meeting the proportionality requirements. In other words, why does the UCI oppose the

organization of Hammer races in a series and approving a corresponding women’s

event? From Velon’s claims, it is questionable whether the UCI has a ‘pre-established

objective, nondiscriminatory and proportionate criteria’ in approving events since

it claims that it never received an explanation as to why its series was

rejected.[21] In addition, the UCI must elaborate

its reasoning in denying a women’s Hammer Stavanger event beyond that it ‘was

not in the best interest of women’s cycling’. The UCI will have to explain why

it not only allegedly threatened to remove Hammer races from the calendar and

denied the inclusion of a women’s race but also why it did not provide Velon a full

response that gave objective justifications, not tied to any economic or

financial interests, as to why it is opposed the organization of a Hammer

Series and a women’s Hammer Stavanger race.

In the end, in order for the ISU to keep its event

pre-authorization scheme it was required to: (a) ‘provide for sanctions and authorization

criteria that are inherent in the pursuit of legitimate objectives’, (b)

‘provide for objective, transparent and non-discriminatory sanctions and

authorization criteria’ that are proportionate to its objectives, and (c) ‘provide

for an objective, transparent and non-discriminatory procedure for the adoption

and effective review of decisions’ concerning the ‘authorisation of speed

skating events’.[22] The Commission will likely

evaluate the UCI’s pre-authorization scheme in light of these criteria.

4.2.1. The UCI’s

pre-authorisation scheme in light of the ISU criteria

This examination will begin by investigating the

second and third criteria before returning to the first criteria. On the second

criteria, the UCI lays out the sanctions for participating in ‘forbidden races’

in Part 1 of its Regulations under Article 1.2.021 that plainly states that

breaches ‘shall render the licence holder liable to one month’s suspension and

a fine of CHF 50 to 100’. Since the sanction is not nearly as draconian as the

ISU’s sanctions, the UCI may have a greater chance of arguing that it is

proportionate to its objective, although it could still be argued that the

sanction does not give much flexibility depending on the circumstances of the

case.[23]

Concerning the event authorization criteria, the UCI explains the requirements

to register a race in the international calendar in the ‘Registration Procedure

for UCI Calendars 2020/2020-2021’, which sets out

the financial obligations of event organizers, the relevant deadlines, and the documentation[24] that

event organizers will have to provide. In addition, the UCI does not have the

same intrusive financial disclosure requirements, which was strongly rebuked by

the Commission.[25] However, nowhere does it explicitly

mention ‘an interest of cycling’ criteria, which makes it a real wonder as to

why this was the reason given, according to Velon, concerning the rejection of the

women’s Hammer Stavanger race. Consequently, the Commission will have to

examine whether the criteria are in practice applied in a uniform and

non-discriminatory manner and whether the UCI uses other criteria to assess the

inclusion of an event on the international calendar. The Commission did not condone

the ISU’s non-exhaustive list of criteria and the broad margin of discretion it

had in approving or rejecting event applications.[26]

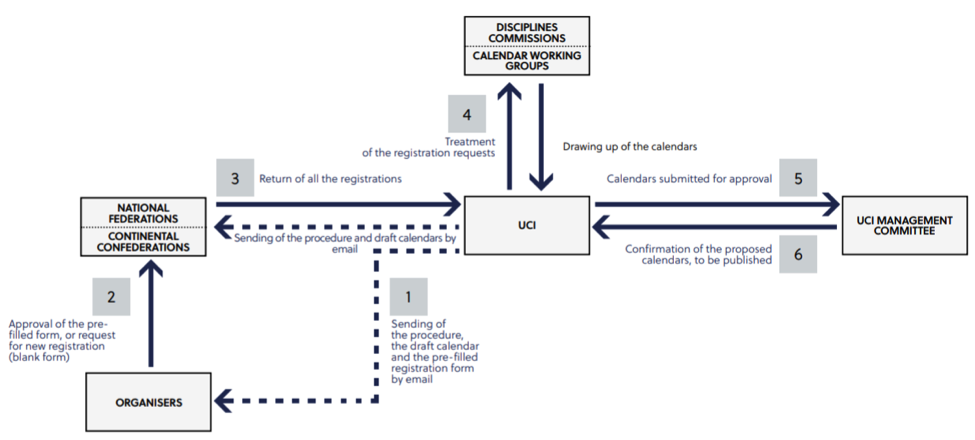

On the third criteria, the UCI does have a rather transparent

process (see flow chart below[27])

concerning the adoption of its calendar, and it also has a process for the

review of a rejection of an event application.[28] If

the UCI management committee rejects an application, the event organizers may

have the opportunity to defend the application. If it does not have this

opportunity, the organizer may appeal to the UCI’s arbitral board, however, the

decision is final and cannot be appealed further. It is at this point that the

UCI’s event pre-authorization scheme may run into further difficulties meeting

the ISU criteria because it does not even allow the possibility for the

organizer to appeal to the CAS. Even the ISU in its Communication No.

1974 allowed for an appeal to the CAS, which still did

not preclude the Commission from questioning the extent an appeals arbitration

would ensure the effectiveness of EU competition law, to which it concluded

that an appeal to the CAS reinforced the restriction of competition.[29] Against

this background, the Commission would likely find the UCI’s grip over the

review process restrictive of competition.

Returning to the first of the ISU criteria, the

question is whether the UCI’s sanctions and pre-authorization criteria are

inherent in the pursuit of a legitimate objective. Considering the above, it is

doubtful whether the potentially open list of criteria and the limited

effective review of decisions could be considered inherent in the pursuit of a

legitimate objective such as ‘the organisation and proper conduct of sport’. Furthermore,

Velon’s case may turn on how well it can demonstrate that it has been unjustly

put under pressure from the UCI.

4.3. Final thoughts on

the ‘hampered’ series

It appears that the UCI has allegedly wielded its

regulatory power through its event pre-authorization scheme to force Velon to

remove a critical aspect of its races: the series. The UCI’s alleged move is

further puzzling by the fact that none of the Hammer races interfere with the men’s

or women’s World Tour race calendar (with the exception of Il Lombardia and

Hammer Hong Kong), meaning that teams and riders would anyway be available. Even

if there was an interference, it is important to keep in mind that professional cycling teams are usually sufficiently

large and organized to compete in more than one race in the world

simultaneously.

Finally, while the UCI did not actually remove the men’s Hammer races from

the

calendar, just an imminent threat of

doing so may be sufficient to restrict competition. Cyclists are severely discouraged to

participate in non-authorized events considering the sanctions they may face.

Hence, event organizers, such as Velon, are completely reliant on the UCI to

approve their events in order to have any chance at a successful and economically viable event,[30] and consequently, Velon cannot risk losing the UCI’s

approval for the Hammer races. Furthermore,

the UCI has in practice already denied a women’s race at Hammer Stavanger,

which greatly strengthens Velon’s claims against the UCI. Lastly, given the vagueness

of the claim that the UCI overall hampered the development of the Hammer

Series, it is possible that there are additional details that have not been

publicized that could further support a potential violation of EU competition

law by the UCI.

5. Conclusion

Velon has also requested interim measures that would

force the UCI’s approval of a women’s race during Hammer Stavanger 2020. However, since interim

measures are rarely granted,[31] it is unlikely Velon will succeed

on this front. Nevertheless, based on the discussion above, there are quite a

few signs that the UCI has perhaps overstepped its regulatory powers. The UCI’s

alleged actions, especially its opposition to the organization of a women’s

Hammer Stavanger race, beg the question as to how it will defend its decision as

pursuing legitimate objectives and respecting the proportionality requirements.

Moreover, it should be recalled that Velon’s complaints also concern the UCI’s

equipment regulations and that there is a completely separate complaint from the Lega del Ciclismo Professionistico. Thus, due to the

large territorial scope and the potentially wide range of actors affected by

the UCI’s actions in these cases, it would be a missed opportunity if the

Commission declines to further elucidate how sport governing bodies must exercise

their regulatory powers in order to comply with EU competition law, especially

when their own financial interests may be in play.