UEFA announced on 8

May that it had entered into Financial Fair Play settlement agreements with 10 European

football clubs. Together with the four other agreements made in February 2015, this brings the total to 14 FFP

settlements for 2015 and 23 since UEFA adopted modifications in its Procedural

rules and allowed settlements agreements to be made between the Clubs and the Chief

Investigator of the UEFA Club Financial Control Body (CFCB).[1]

In the two years during

which UEFA’s FFP regulations have been truly up and running we have witnessed the

centrality taken by the settlement procedure in their enforcement. It is

extremely rare for a club to be referred to the FFP adjudication chamber. In

fact, only the case regarding Dynamo Moscow has been referred to the adjudication chamber. Thus, having

a close look at the settlement practice of UEFA is crucial to gaining a good

understanding of the functioning of FFP. Hence, this blog offers a detailed

analysis of this year’s settlement agreements and compares them with last year’s settlements.

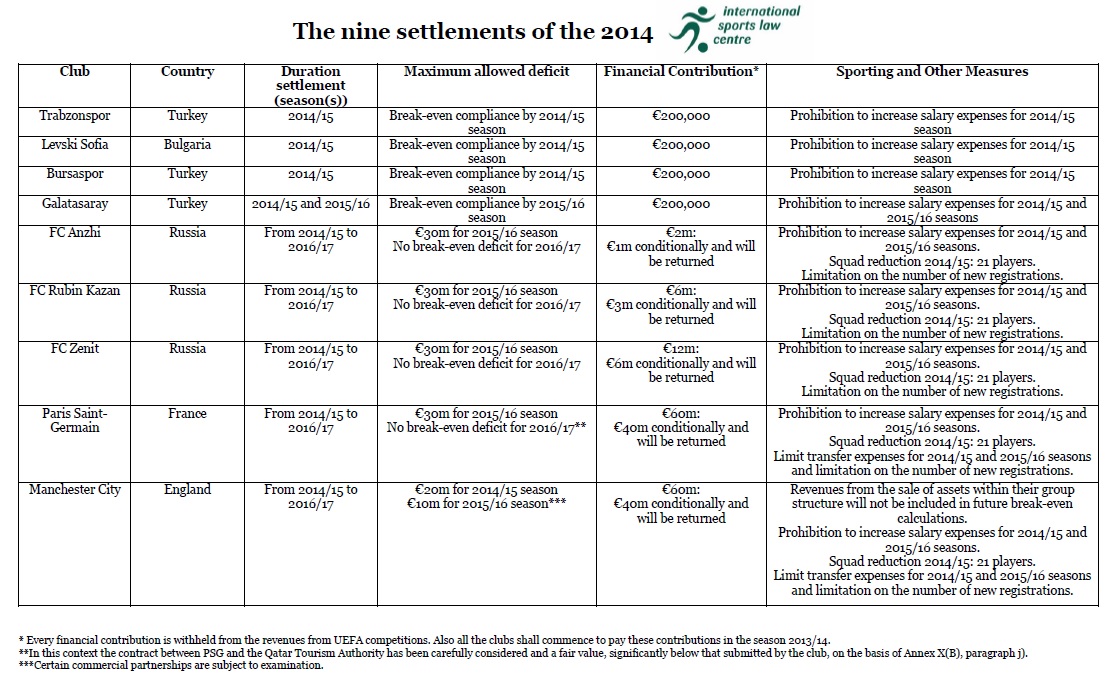

The two tables below

provide an overview of last year’s nine settlement agreements (table 1) and

this year’s settlement agreements (tables 2 and 3).

Table2014.jpg (310KB)

.jpg.axdx)

Table2015(1).jpg (259.6KB)

.jpg.axdx)

Table2015(2).jpg (228.4KB)

DIFFERENCES WITH LAST YEAR’S SETTLEMENTS

The financial contribution (fines)

In 2015, the financial

“sanctions” have been much lower than last year, especially with regard to the

highest penalties. In 2014, Paris Saint-Germain and Manchester City agreed to

pay an overall of €60 million (€40 million, subject to the fulfilment of the

conditions imposed by UEFA to the club). This year, the two highest financial

contributions will be those of FC Internazionale (€20 million) and AS Monaco

(€13 million). Moreover, the contributions imposed on FC Internazionale and AS

Monaco have a conditional element: should the clubs fulfil UEFA’s requirements,

they will get €14 million and €10 million returned to them respectively.

Last year, the

revenues derived by the clubs from participating in European competitions were

withheld by UEFA in every settlement agreement. However, this year, UEFA will withhold

revenue from the UEFA competitions in only some cases, namely for FC Krasnodar,

FC Lokomotiv Moscow, Besiktas, AS Roma, AS Monaco and FC Internazionale.

Moreover, another

difference concerns the way the club may pay the ‘conditional amount’ provided

in the settlements. Last year, the conditional amounts were “withheld and

returned” to the club, provided it fulfilled the “operational and financial

measures agreed with the UEFA CFCB”. This year, however, these conditional

amounts “may be withheld in certain circumstances depending on the club’s

compliance”. This means that there is no a priori retention of the money by UEFA

that is subject to the achievement of the objectives agreed.

The deficit limits

As can be seen from the

tables above, UEFA limits the total deficit that clubs are allowed to have. The

clubs must comply with this UEFA obligation for one or two seasons, depending

on the settlement agreement. This condition was imposed in both the 2014 and

2015 agreements. Yet, some differences arise with regard to the deficit allowed

for clubs.

These differences

become apparent when comparing FC Rubin Kazan (2014) with AS Roma (2015). Both clubs

agreed to a three seasons duration of the settlement, a €6 million fine, a

reduction of the squad (22 players for AS Roma and 21 for FC Rubin Kazan), and

a limitation on the number of player registrations. However, the maximum

allowed deficit for each club is different. As regards AS Roma, UEFA restricted

the deficit authorized to €30 million. It should be noted that, according to

UEFA’s own regulations, the maximum acceptable deviation is €30 million.[2] In

other words, this is not a real sanction imposed on AS Roma, since every European

club has the duty to comply with the maximum acceptable deviation rule. In its agreement

with FC Rubin Kazan, on the other hand, UEFA imposed a deficit limit of €30

million for the first season and full break-even compliance for the following

season. This is a harsher sanction than in the agreements found in 2015, in

which a specific deficit is permitted for the second season of the settlements

(see the FC Krosnodar, AS Roma, Besiktas and AS Monaco agreements).

The salary cap

This salary cap measure is regulated in

Article 29(1)(g) of the Procedural Rules Governing the UEFA Club Financial

Control Body. According to this provision, a salary cap is a “restriction

on the number of players that a club may register for participation in UEFA

competitions, including a financial limit on the overall aggregate cost of the

employee benefits expenses of players registered on the A-list for the purposes

of UEFA club competitions”.

In 2014, every

settlement reached by the clubs with UEFA prohibited the increase in salary

expenses for the first season following the agreement. In 2015, this condition

was not stipulated in all of the agreements. More concretely, the agreements

settled with Ruch Chorzów, Panathinaikos, Hapoel Tel Aviv, and Hull City, do

not include a salary cap.

Changes have also

occurred regarding the structure of the salary cap imposed. In 2014, a unitary

interpretation of the salary cap

provision was used by UEFA. In the case of Manchester City, for of example, UEFA

stated that “employee benefit expenses cannot be increased during two financial

periods”.[3]

In 2015, however, UEFA

used two different ways to ‘cap’ salaries:

In the cases of the FC Rostov,

CSKA Sofia and Kardemir Karabükspor settlements, it held that “the total amount of the Club’s aggregate cost of employee benefits

expenses is limited”.

With regard to FC Internazionale and Besiktas, the settlements hold that

“the employee benefit expenses to revenue ratio is restricted and that the

amortisation and impairment of the costs of acquiring players’ registration is

limited.”

The first alternative

is similar to the solution adopted in 2014 to cap players’ wages. As UEFA

releases only some elements of the settlements, the precise levels of the cap

imposed remain unknown, as was the case last year. The mechanism used by UEFA in

the case of Besiktas and FC Internazionale is different. It is based on a fixed

ratio between employee benefit-expenses and the clubs revenue. The cap becomes

more dynamic, as it is coupled to another variable, the revenue of the club,

but also less predictable.

Is the settlement a sanction or an agreement?

According to UEFA’s regulations, the UEFA CFCB Investigatory Chamber has

the power to negotiate with clubs who breached the break-even compliance

requirement as defined in Articles 62 and 63 UEFA Club Licensing and Financial

Fair Play Regulations. If a settlement is not reached, the CFCB Adjudicatory

Chamber will unilaterally impose disciplinary sanctions to the respective clubs.

The ‘settlement

procedure’ allows for a certain degree of negotiation between the parties. Settlements

are likely to be in the interest of both parties. Firstly, by agreeing to

UEFA’s terms, the club secures its participation in European competitions which,

in many cases, are one of its main sources of revenue. Not agreeing to the

terms would entail risking a much bigger sanction. Naturally, such a sanction

can be appealed in front of the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS), but such

a procedure would be expensive, time consuming and does not guarantee a better outcome.

To UEFA, a settlement is a guarantee that the case ends there, that its FFP

regulations do not get challenged in front of the CAS, but also that it does

not need to invest resources to fight a long and costly legal battle. Moreover,

the settlement procedure provides the flexibility needed for a case-by-case

approach to the sanctions.

CONCLUSION

The settlement

procedure is a key element to the current implementation process of the UEFA

FFP regulations. UEFA is still in the learning phase concerning FFP and the

recourse to settlements is a way to provide for much needed regulatory flexibility.

Even if the settlements have many advantages for all the parties involved, they

also have detrimental effects. It is regrettable that they are not published in

full, even if slightly redacted, so that clubs may enjoy a higher legal

certainty when facing an FFP investigation. This lack of transparency makes it

harder to predict and rationalize the sanctions imposed and exposes UEFA to the

risk of being criticized for the arbitrariness of its settlement practice.

This year’s

settlement harvest was undoubtedly more lenient than in 2014. UEFA has

apparently decided to water down its FFP sanctions, maybe to make sure that FFP

survives the many legal challenges ahead. The balance between under-regulation,

that would render FFP toothless, and over-regulation, that would make it

difficult for clubs to invest and take risks, is indeed very difficult to find.

UEFA’s settlement practice is a soft way to walk this complex line.

[1] Article 14(1)(b) and

Article 15 of the Procedural Rules Governing the UEFA Club Financial Control

Body – Edition 2014.

[2] Article 61 UEFA Club Licensing and Financial Fair Play

Regulations

[3] Decision of the Chief

Investigator of the CFCB Investigatory Chamber: Settlement Agreement with

Manchester City Football Club Limited (2014)