Editor’s

note: Shamistha Selvaratnam is a LLM Candidate of the Advanced Masters of

European and International Human Rights Law at Leiden University in the Netherlands.

Prior to commencing the LLM, she worked as a business and human rights

solicitor in Australia where she specialised in promoting business respect for

human rights through engagement with policy, law and practice.

The consumer

goods industry is shaped by businesses’ desire to engage with the best-quality

suppliers at the cheapest price in order to sell goods at a high-profit margin

in the burgeoning consumer markets. Accordingly, they continue to build their

value chains in order to provide goods to consumers. The resulting effect of

this is that potential human rights risks and impacts are likely to arise in

the supply chains of businesses that operate in the industry. Risks that often

arise in this sector include forced labour, non-compliance with minimum wage

laws and excessive work hours, land grabbing and discrimination. Accordingly,

businesses such as Unilever face the challenge of preventing, mitigating and

addressing adverse human rights impacts in their supply chains through

conducting human rights due diligence (HRDD). As Paul Polman (former CEO of

Unilever) has stated:

‘We cannot choose between [economic]

growth and sustainability—we must have both.’

This fourth blog of a series of articles

dedicated to HRDD is a case study looking at how HRDD has materialised in

practice within Unilever’s operations and supply chains. It will be followed by

another case study examining another that has also taken steps to

operationalise the concept of HRDD. To wrap up the series, a final piece will

reflect on the effectiveness of the turn to HRDD to strengthen respect of human

rights by businesses.

Company Background[1]

Unilever PLC (Unilever) is a consumer goods

company that is co-headquartered in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. It

is considered to be one of the world’s leading consumer goods company, making

and selling around 400 brands (including Dove, Lipton and Magnum) in the

personal care, foods, home care and refreshment categories in more than 190

countries. Unilever is also the second largest advertiser globally and creates

content to market its products using digital channels. It employs more than 155,000

people globally and over two billion people use its products daily.[2]

Unilever has a complex global value chain,

with its global manufacturing operations spanning across approximately 76,000

suppliers and 300 factories in 69 countries in order to produce products of

almost 19 million tonnes. Its products are distributed through a network of

more than 400 warehouses to 26 million retail stores, including large

supermarkets to small convenience stores and e-commerce channels.[3]

Unilever endorsed

the UNGPs in 2011 and recognises that it has ‘the responsibility to respect

human rights and the ability to contribute to positive human rights impacts.’[4]

It states that it follows and supports the OECD Guidelines.[5]

Unilever acknowledges

that there is ‘both a business and a moral case for ensuring that human rights

are upheld across [its] operations and [its] value chain.’ As a result, it seeks to identify human

rights risks that it may be involved in through its activities or business

relationships through conducting HRDD and integrating the responses into its

policies and internal systems, acting on the findings, tracking its actions and

communicating with its stakeholders.[6]

Unilever was the first company to pilot the Shift and Mazars UN Guiding

Principles Reporting Framework, which resulted in its Human

Rights Report 2015 – Unilever’s disclosure to the Reporting Framework in

2015 is accessible here.

Unilever’s human rights work is overseen by

the CEO and supported by the Leadership Executive, including the Chief

Supply Chain Officer, which includes the Chief Supply Chain Officer, Chief

Legal Officer, Chief Sustainability Officer and the Global Vice President for

Social Impact.[7] Unilever’s Procurement Team leads its supply chain efforts. There is

no publically available information on the size and resources of this team, its

role or where team members are located.

Identification and Assessment of Risks

Unilever’s process for identifying its

salient human rights risks started with a workshop facilitated by Shift.

Unilever considered the range of potential human rights impacts resulting from

its activities, and prioritised those likely to be the most severe were they to

occur, based on how grave the impacts to the rights-holder could be, how

widespread they are and how difficult it would be to remedy any resulting harm.[8]

Unilever drew from previous conversations with external bodies, including the

Work Economic Forum Human Rights Global Agenda Council, the Global Social

Compliance Programme and the UN Global Compact.[9]

It also drew from external data sources such as governments, international

agencies and risk organisations that assist it to monitor changes in human

rights situations in the countries in which it operates, as well as from

understanding of the perspectives of affected stakeholders and verification

with expert stakeholders of the salient issues identified.[10]

Following this initial risk assessment,

Unilever conducts regular human rights impact assessments (HRIAs), 'which

include on-site visits by third-party experts who engage and consult

rights-holders and other stakeholders.’[11]

For example, in 2016 it commissioned a human rights impact assessment of its

own operations and value chain in Myanmar in order to identify impacts on

'local right-holders, including workers, their families and other community

members'.[12]

This assessment 'uncovered regular patterns of discriminatory practices within

some suppliers in [its] extended supply chain'. In addition, during the

assessment of the harvesting of palm sugar activity, 'children were found to be

working alongside their parents as they prepared palm juice, whilst palm sugar

tree climbers were using unsafe homemade ladders to pick the fruit'.[13]

Unilever considers that

its suppliers play a critical role in helping it source responsibly and

sustainably.[14]

Accordingly, Unilever developed a Responsible

Sourcing Policy, which sets out Unilever’s

expectations with regards to the respect for the human rights, including labour

rights, of the workers in its extended supply chain. It is based upon 12

fundamental principles that are derived from internationally recognised

standards and include treating all workers equally with respect and dignity,

paying workers fair wages and ensuring working hours of all workers are

reasonable.

Clauses are included in

supplier contracts in an effort to ensure that suppliers respect and comply

with a set of Mandatory Requirements related to each of the fundamental

principles set out in the Responsible

Sourcing Policy.[15] For example, with respect

to workers being paid fair wages, suppliers are required to ensure that all

workers are provided total compensation packages that include wages, overtime

pay, benefits and paid leave which either satisfies or exceeds the legal

minimum standards or industry standards, whichever is the highest. Guidelines

and tips are provided for the implementation of a comprehensive and robust

process so suppliers can meet the Mandatory Requirements and move up the

‘continuous ladder of improvement’ and advance to good practice and then

finally achieve and maintain best practice with respect to each of the fundamental

principles.

Where there are

breaches of the Responsible

Sourcing Policy, they must be reported to

Unilever who will investigate and discuss its findings with the relevant

supplier. If remediation is required, the supplier is required to devise and

inform Unilever of their Corrective Action Plans (CAPs) and implementation

plans and timeline to resolve the breach.

Unilever’s Procurement

Code Committee evaluates and makes recommendations where suppliers are not

willing to comply or move up the continuous improvement ladder, and it reviews

all key incidents raised. Continual non-conformances with no remediation plans

result in an escalation to the Global Procurement Code Committee for a decision

on terminating the business relationship.[16] No information is

publicly available regarding Unilever’s Global Procurement Code Committee.

Engaging with new

and existing suppliers[17]

Unilever’s audit approach to evaluating suppliers is depicted

below.

Source: Unilever 2015 Human Rights

Report, p 18

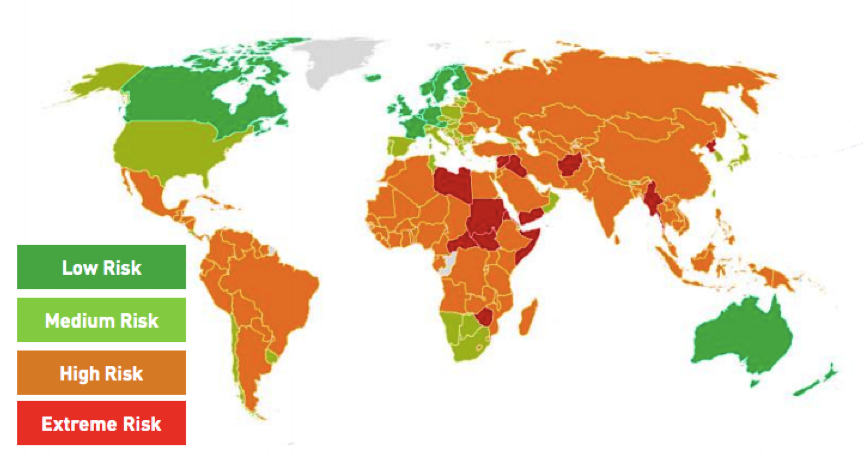

Unilever uses a risk-based approach to evaluate prospective and

existing suppliers. Suppliers are required to complete a self-declaration

regarding their compliance to the Mandatory Requirements of Unilever’s Responsible

Sourcing Policy. Suppliers are then segmented

based on a risk assessment using externally available indices of business and

human rights risks from expert sources. Country risk is

one element of the risk assessment (see below for the outcome of Unilever’s

2018 country risk assessment).

Source: Unilever’s

Supply Chain, p 17.

Suppliers in the

highest risk segment are required to undergo an independent third-party audit.

Raw material or finished goods suppliers are required to undergo an on-site

audit, while service suppliers need to undergo a remote desktop audit.

During the course of an

on-site audit, all non-conformances are recorded to indicate where a supplier’s

site does not align with the Responsible

Sourcing Policy Mandatory Requirements. A

supplier must provide a time-bound CAP to address and remediate non-conformances, and

the auditor must confirm the remediation has effectively addressed the non-conformance

in a follow-up audit within a 90-day period for the supplier to be Responsible

Sourcing Policy compliant.

Audit frequency can be

every 12, 24, or 36 months, and is determined by the number and type of

non-conformances found in the previous audit. CAPs must be implemented to

address all non-conformances and re verified in a follow-up audit to confirm

and verify that the identified issues have been effectively remediated.[18]

As at May 2018, of the 44,290 suppliers risk assessed to date, 11,287 were

classified as high risk of which 1,667 were identified with issues in the

previous three years of which 1,175 had verified CAPs.[19]

More serious non-conformances

are classified as ‘Critical Incidents’, with the most severe of these termed

‘Key Incidents’. The presence of Critical Incidents automatically means

that the supplier must have a new audit after 12 months. On top of the

requirements for Critical Incidents, the auditor must raise a Key Incident

to Unilever within a 24-hour period. Key Incidents are escalated to either

Director or Vice President level within Unilever to ensure appropriate

attention is given. Within seven days a CAP to remedy the issue

must be provided by the supplier.

Stakeholder Engagement Channels

Unilever engages with its

stakeholders in conducting risk assessments. Stakeholder consultation, dialogue

and action are considered to be a critical part of its risk assessment process

and have been said to deliver ‘enormous value’, given the localised and

culturally specific nature of the issues faced. Unilever has identified its

stakeholders to include its employees, trade unions, customers, NGOs,

communities, suppliers, workers, business partners, advisory boards (such as

the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan Council), governments, intergovernmental

organisations and civil society organisations.[20] Unilever’s Advocacy Team

play a lead role in engaging with its external stakeholders, which is supported

by its External Affairs Team.[21] Unilever also engages

with various organisations including the World

Business Council for Sustainable Development, Consumer Goods Forum, United

Nations Global Compact and the World Economic Forum.

Unilever also captures

and addresses complaints through its grievance mechanisms – it notes that ‘Grievance mechanisms play a critical role in

opening channels for dialogue, problem solving, investigation and, when

required, providing remedy.’[22] With respect to

Unilever’s supply chain, one of the fundamental principles of the Responsible

Sourcing Policy requires all workers to have

access to fair procedures and remedies. Accordingly, suppliers are required to

provide grievance mechanisms to their workers. Unilever monitors the number of

complaints received from workers by suppliers each year in order to monitor its

salient issues and address root causes so that similar grievances will not be

raised in the future.[23] Additionally, Unilever

also provides a hotline that anyone can access to report on responsible

sourcing issues. It has also developed a grievance

procedure for workers in its palm oil supply chain.

A summary of the complaints raised under this procedure can be found here.

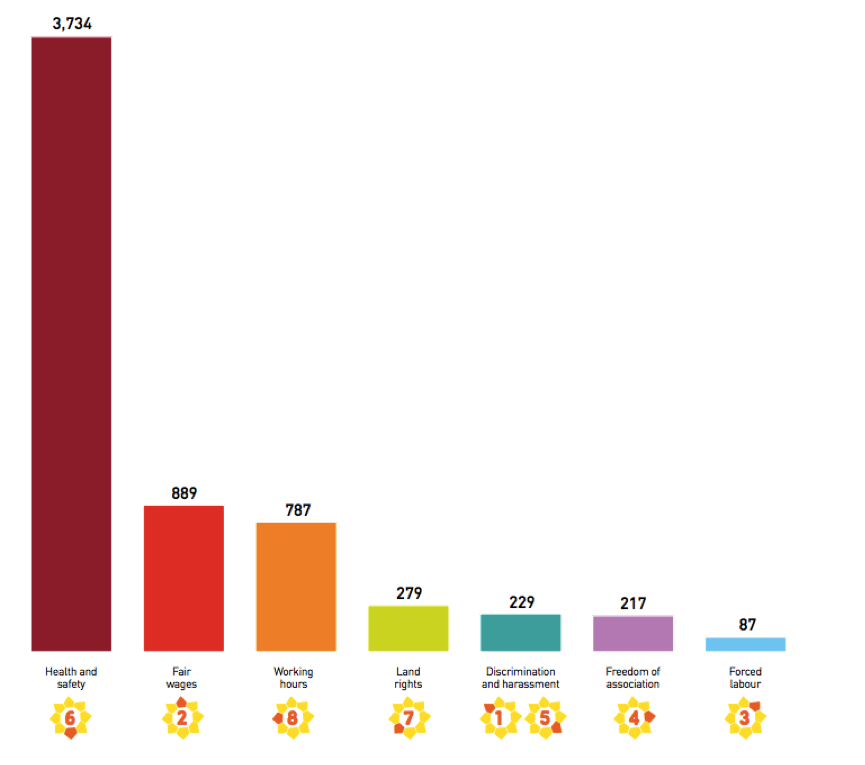

Identified risks

Through its risk

identification and assessment processes, Unilever has identified eight salient

human rights issues within its business, which are depicted in the image below.

Source: Unilever

Human Rights Report 2015, p 26.

During the course of

2017, Unilever identified the following non-conformances in relation to the

salient issues:

Source: Human

Rights 2018 Supplier Audit Update, p 10.

Integrating and Acting

Unilever recognises that it must take steps to identify and

address any actual or potential adverse impacts with which it may be involved

whether directly or indirectly through its own activities or its business

relationships. It seeks to manage the risks identified in the processes

discussed above by ‘integrating the responses … into [its] policies and

internal systems, acting on the findings, tracking [its] actions, and

communicating with [its] stakeholders about how [it] address impacts.’[24]

Remediation is perceived as important as addressing human rights impacts.

With respect to each of the eight salient issues set out above,

Unilever has taken specific actions and implemented initiatives to prevent and

mitigate those issues from arising in its supply chains. For example, with

respect to forced labour Unilever has, inter alia:[25]

- Developed best practice guidelines on the use of

migrant labour focusing on the recruitment process, contractual terms and the

payment of wages and benefits. These guidelines are not publicly available.

- Incorporated human trafficking explicitly into

its Human Rights Policy Statement, Code of Business Principles and its Respect,

Dignity and Fair Treatment Code Policy, and provided associated training to its

employees globally.I

- Incorporated trafficking guidelines into its Responsible

Sourcing Policy and Responsible Business Partner Policy.

- Published a UK Modern Slavery Statement in 2017, 2018 and 2019.

- Became a founding member of the Leadership Group for

Responsible Recruitment, which promotes responsible recruitment

practices by business.

- Provided training to suppliers in Turkey, Dubai,

India, Bangkok and Malaysia on eradicating forced labour and the responsible

management of migrant labour.

Tracking

Unilever recognises

that ‘the ability to track and monitor issues is a vital part of measuring

progress in remediation and addressing grievances’.[26] The Unilever Board is

responsible for compliance, monitoring and reporting and day-to-day

responsibility lies with senior management. Unilever’s Corporate Audit Team and

external auditors undertake checks on this process. [27]

With respect to

tracking its supply chain, Unilever has an ‘Integrated Social Sustainability

Dashboard’ (Dashboard), which sets out the ‘number of non-conformances for each

fundamental principle of the RSP’.[28] It uses the information

available through the Dashboard to identify salient hotspot issues ‘allowing

use to prioritise, build guidance produce webinars, and support regions where

the need is greatest’.[29] Unilever’s Procurement

Team also monitors supplier compliance levels and identifies when intervention

is required. It works with suppliers to ensure effective remediation. Unilever also

tracks and verifies that CAPs are implemented within the agreed timelines. When

very serious Key Incidents occur, Unilever more directly and actively

participates in developing CAPs and following up on their implementation.[30]

Communicating

Unilever claims that it engages in dialogue

with its employees, workers and external stakeholders who are or could

potentially be affected by its actions.[31]

It particularly focuses on individuals or groups who ‘may be at greater

risk of negative human rights impacts due to their vulnerability or

marginalisation’.[32]

Unilever primarily uses its Human

Rights Report 2015 and Human

Rights Progress Reports to communicate its process of identifying and

assessing human rights risks and impacts, including its salient human rights

issues and the actions taken to prevent and mitigate those issues, as well as

integrating, acting and tracking those issues. Unilever also utilises its

annual Modern Slavery Statements to communicate with stakeholders. Aside from these

reports and statements, Unilever has not clearly stated what other means it

utilises to communicate its human rights impacts, policies and approaches. A

review of its website contains a webpage

detailing its engagement with stakeholders, but fails to recognise exactly how

this engagement is carried out.

With respect to grievances raised through the Palm Oil grievance

procedure, Unilever publishes a Grievance Tracker

online setting out a summary of each grievance raised, the link to Unilever and

the latest actions taken to address the allegations. It also publishes

responses in relation to specific claims – see for example here and here.

The

Gaps Between Theory and Practice

Unilever

has acknowledged that the challenges faced by the

business community with regard to its responsibility to respect human rights

are ‘enormous’, particularly given the scale of their operations and supply

chain. It states that ‘the

risk of systemic human rights abuses exists across our value chain and the

value chains … This is a reality we must confront and work together to

resolve.’ As a result it has claimed

to go beyond respecting human rights to actively promoting them. This approach

has positioned it publicly as a leader and a model from which other businesses

can draw inspiration.[33]

What is clear from a review of Unilever’

human rights approach is that it recognises its responsibility to respect human

rights and has sought to take steps to fulfil this obligation along its entire

value chain. While Unilever’s human rights efforts started to gain some

momentum in 2010 when it launched its Sustainable Living Plan and began

evaluating suppliers, it accelerated its efforts in 2014 by introducing a Human

Rights Policy Statement, formalising its commitment to promoting human rights

across its operations and supply chains, as well as through designing a

five-year human rights strategy.[34]

In 2015, it became the first company to produce a standalone human rights

report.

Nonetheless, despite Unilever’s extensive

human rights work over the past years, including the strengthening of its HRDD

processes in its supply chains, it has drawn and continues to draw criticism in

relation to the human rights abuses that still exist within its value chain.

Key human rights issues that have been placed in the spotlight in various

jurisdictions are discussed below. Information regarding alleged human rights

violations committed by Unilever pre-dating the UNGPs has been included in the

sub-sections below to the extent that such violations have been found to still

be present following Unilever’s actions to increase its efforts to respect

human rights in 2014.

Vietnam

In 2013, Oxfam (together with Unilever)

published a report

in which it assessed the labour standards in Unilever’s operations and supply chain

in Vietnam and developed measures to guide Unilever (and other companies) to

fulfil their social responsibilities. It found that despite Unilever’s

commitment to human rights, its tools and processes for due diligence and

remediation via grievance mechanisms needed to be strengthened. It stated that

Unilever had ‘not been aware that some of its practices were associated with

adverse impacts for workers, including wages that were legal but low, excessive

working hours, and high levels of contract labour.‘[35]

Recommendations were made by Oxfam to Unilever, including policy changes,

strengthening its due diligence processes and better aligning business

processes with its policies. Unilever made a range of commitments in response

to the recommendations.

A progress

report was published in 2016, which found that Unilever’s ‘overall

commitment to respecting human and labour rights has been strengthened as a

result of effective leadership across the business’. Nonetheless, it identified

some ‘critical implementation challenges’ that need to be addressed in order to

‘[translate] the company’s policy commitments into practice and achieve

positive outcomes for … workers’. Specific issues that were identified were:

- There was an ‘unresolved tension’ between the commercial and labour

standards imposed on suppliers. Some suppliers did not see the business case

for their own businesses in improving their labour standards.

- Despite Unilever’s efforts to ensure fair compensation for workers,

there was a lack of evidence to show that worker wages had increased beyond the

legal minimum level in Vietnam.

Additionally, Oxfam highlighted that

multinational more generally need to address the root causes of adverse human

rights impacts in their supply chains in order for ‘good labour standards to

become universal operating conditions.’ Oxfam made further recommendations to

improve the situation for workers in Vietnam.

India

In the 2011

SOMO & ICN Report, SOMO also reported on Indian tea plantations that

supply to Unilever. Issues identified included wages being paid with too little

benefits, workers being discriminated against in relation to promotions and

benefits, the casualization of labour as well as violations of the freedom of

association. In 2016, ICN released a follow

up report on the situation in India. It found that there had been some

improvements in the ‘payment of minimum wages, setting up procedures for safe

handling of chemicals and the provision of basic medical care and educational

facilities for all temporary and permanent workers’. However, there are still

‘many serious non-compliances’ relating to ‘unequal benefits for casual

workers, overtime wages and working hours, advance payments, chemical handling

practices and worker representation.’ Unilever responded

by stating that it was in dialogue with its suppliers in relation to the issues

raised in the follow up report.

Further, in 2015 a BBC investigation

found ‘dangerous and degrading living and working conditions’ in tea estates

that supply to some of Unilever’s brands (Lipton and PG Tips). Unilever stated that it

regarded the issues raised in the investigation as ‘serious’ and had made

progress to rectify these issues through ‘working with [its] suppliers to

achieve responsible and sustainable practices’.

Turkey

In 2014, an external organisation engaged by

Unilever carried out an independent

assessment of its tea supply chain in Turkey. The assessment found, inter

alia, that workers worked excessive hours during the harvest, various health

and safety issues (e.g. lack of protective equipment) and migrant worker

accommodation did not meet the required standards in some instances. As a

result, Unilever decided to remediate the identified issues at the individual

site level and also work with external multi-stakeholder groups to address more

systemic challenges. It also started a capacity

building initiatives in Turkey that focuses on human rights and held training

in 2016 focusing on the key non-compliances found.

Indonesia

In 2016, Amnesty International published a report

in relation to labour exploitation on plantations in Indonesia that provide

palm oil to Wilmar, which then supplied to Unilever.[36]

It was found that serious human rights violations were occurring on the

plantations of Wilmar and its suppliers, including ‘forced labour and child

labour, gender discrimination, as well as exploitative and dangerous working

practices that put the health of workers at risk’, which resulted from

systematic business practices (e.g. low wages and the casualisation of labour).

Unilever issued a detailed

response to a letter from Amnesty International in relation to the report

recognising that ‘more attention needs to be paid to social issues at palm oil

plantations and that current processes and policies need to be improved to

ensure they address issues effectively and create more transparency.’ It also

noted that it was in contact with Wilmar regarding the issues raised and

committed to continuing to engage to take steps to ‘close the gaps identified’.

Unilever also issues a public

statement once the report was released, committing to investigating the

grievances raised in the report and addressing them. Unilever has continued to

engage with Wilmar and Amnesty International on these issues – see for example here

(2016), here

(2017) and here

(2018).

Conclusion

What is clear from these examples of human

rights violations in Unilever’s supply chains is that despite its extensive

HRDD process that it seeks to roll out across its value chain, in practice

there remain weaknesses and blind spots in this process. For example, Unilever

does not have a third party grievance mechanism allowing workers to raise

complaints directly to the company (except in relation to palm oil). Instead

workers must raise their grievances through supplier provided mechanisms, which

can discourage the communication of human rights issues. Also, Unilever

assesses prospective suppliers through the use of a self-declaration, which is

extremely problematic as it relies on potential culprits to assess their own

compliance with the Mandatory Requirements for doing business with Unilever, in

some cases without verification by Unilever or an independent third party. Weaknesses

such as these make it evident that Unilever has far to go on its journey to

respecting human rights within its supply chains, despite being a ‘leader’ in

implementing HRDD globally. Unilever needs to look beyond remedying human

rights abuses as they are alleged and reported. It must also examine the

systemic failings in its HRDD process that result in these human rights risks not

being identified and therefore prevented or mitigated.

[1] Unless otherwise statement, the information in this section has

been obtained from the Unilever

2018 Annual Report and the Unilever

Human Rights Report 2015.

[4] Unilever

Human Rights Policy Statement, p 4.

[5] Ibid, p 1; Unilever, Advancing Human Rights in our

Own Operations; Unilever

Human Rights Report 2015, p 1.

[6] Unilever

Human Rights Policy Statement.

[7] Business and Human Rights Resource Centre Action Platform, Unilever.

[18] Unilever’s

Supply Chain, p

17.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Unilever

Human Rights Report 2015, pp 22-23; Unilever, Engaging with Stakeholders.

[21] Business and Human Rights Resource Centre Action Platform, Unilever.

[22] Ibid.

[25] Unilever

Human Rights Report 2015, p 32; Unilever, Sharing Best Practice in

Fighting Forced Labour; The Consumer Goods Forum, Business Actions Against

Forced Labour, p 36; Unilever

Human Rights Progress Report

2017, p 32.

[34] Unilever

Human Rights Report 2015, p 3.

[35] Oxfam, Business

and Human Rights: An Oxfam Perspective on the UN Guiding Principles, p 7.