Editor’s

note: Shamistha Selvaratnam is a LLM Candidate of the Advanced Masters of

European and International Human Rights Law at Leiden University in the

Netherlands. Prior to commencing the LLM, she worked as a business and human

rights solicitor in Australia where she specialised in promoting business

respect for human rights through engagement with policy, law and practice.

The tragic collapse of Rana Plaza in Bangladesh

in 2013, which killed over one thousand workers and injured more than two

thousand, brought global attention to the potential human rights risks and

impacts that are inherent to the garment and footwear sector.[1] This sector

employs millions of workers within its supply chain in order to enable

large-scale production of goods as quickly as possible at the lowest cost as

market trends and consumer preferences change.[2]

These workers are often present in countries where the respect for human rights

and labour rights is weak. This creates an environment that is conducive to

human rights abuses. Key risks in this sector include child labour, sexual

harassment and gender-based violence, forced labour, non-compliance with

minimum wage laws and excessive work hours.[3]

Accordingly, brands such as Adidas face the challenge of conducting effective human

rights due diligence (HRDD), particularly in their supply chains.

This third blog of a series of articles

dedicated to HRDD is a case study looking at how HRDD has materialised in

practice within Adidas’ supply chains.

It will be followed by another case study examining the steps taken by Unilever

in order to operationalise the concept of HRDD. To wrap up the series, a final piece

will reflect on the effectiveness of the turn to HRDD to strengthen respect of

human rights by businesses.

Company Background

Adidas Group (Adidas) is an apparel,

footwear and sporting goods company that is headquartered in Germany. As a

business it designs, markets and sells consumer goods globally. Adidas has

more than 2,300 retail stores, 14,000 franchise stores and 150,000 wholesale distributors,

as well as an online store.[4]

It employs more than 57,000 people and produces over 900 million products

globally.[5]

Given that it outsources most of its

production, it has a complex and large scale supply chain, with approximately

700 independent factories that manufacture products in over 50 countries.[6]

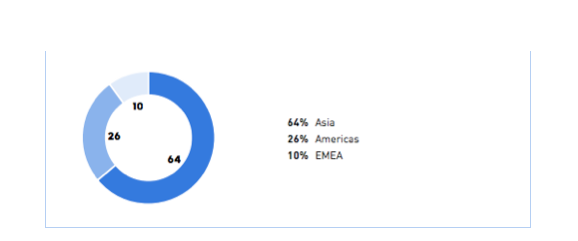

Its supplier factories by region as at

2016 are depicted in the image below. Its top sourcing countries are China,

Vietnam and Indonesia.[7]

Source: Adidas

Sustainability Progress Report 2016, p 61.

Adidas has both direct

suppliers and indirect suppliers (i.e. material and other service providers

that supply goods and services to Adidas’ direct suppliers; licensees which

manage the design, production and distribution of specific products to Adidas;

and agents that act as intermediaries and determine where products are

manufactured, manage the manufacturing process and sell finished products to

the group). Approximately 75% of its total sourcing volume comes directly from

its supply chain, with the other 25% coming from agents or made under licence. The manufactured products are sold in over 100 markets.[8]

Adidas states

that it supports the UNGPs and it is a ‘long time adherent’ to the OECD

Guidelines. It considers

that the corporate responsibility to respect human rights is a ‘global standard

of expected conduct for all business enterprises’ and it states

that it has ‘incorporated key elements of the [UNGPs] into its general practice

in managing the human rights impacts of its business.’

Adidas’ general

approach to human rights is firstly to strive ‘to operate responsibly and

in a sustainable way along the entire value chain’, and secondly to safeguard

the rights of its employees and those that work in its manufacturing supply

chains. HRDD is a key part of this approach. Given the extensive nature of

Adidas’ supply chains, it has taken a targeted approach to HRDD by focusing on

mitigating and remediating issues that arise in high-risk locations, processes

and activities.[9]

It also imposes ‘cascading responsibilities’ on its business partners in order

to ‘capture and address potential and actual human rights issues upstream and

downstream’.[10]

Adidas’ Social and Environmental Affairs team

(SEA Team) is tasked

with, inter alia, ensuring compliance with the Workplace

Standards within Adidas’ supply chains (discussed in further detail below).

The Team consists of approximately 70 individuals, including engineers,

lawyers, HR managers and former members of NGOs. It is organised into three

regional teams covering Asia, the Americas and Europe, Middle East and Africa.

The Team collaborates with other functions within Adidas, including Legal and

Human Resources. The Team works collaboratively with other functions, including

Legal, Sourcing and Human Resources. It engages directly with suppliers,

governments and other external stakeholders as and when required.

Identification and Assessment of Risks

Adidas engages in a range of processes to

identify and assess its human rights risks and impacts on a continuous basis

within its supply chains. Adidas’ SEA Team engages commissioned third party

experts and independent audits as part of this process where necessary.[11]

Adidas completes annual

Country Risk Assessments (CRAs), which are not publically available, in the

countries in which it sources products whereby it reviews the salient human

rights issues and risks in a particular country. CRAs are informed by various

people, including Adidas’ field teams, its engagement with local stakeholders,

concerns raised by international NGOs, as well as an examination of regional

human rights reports (as necessary). The risks identified in these CRAs

inform its priorities and guides its prevention and mitigation strategies,

particularly in relation to its supply chain monitoring.

Entry

into new countries

Where Adidas plans to enter a new sourcing country, in-depth

assessments are normally undertaken over a period of one to two years. The

process involves engagement with government departments, international agencies

and civil society groups to determine country level risks and issues. This

process informs whether Adidas should or should not enter a particular country,

as well as whether additional processes should be undertaken to safeguard

against particular adverse human rights impacts that are common within a

country arising within Adidas’ supply chains.

Engaging with new

suppliers

All new supplier relationships must be disclosed to Adidas’ SEA

Team for approval.

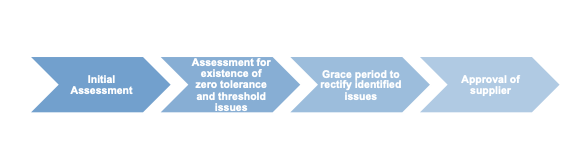

The process followed by Adidas when considering entering into

direct supplier relationships is illustrated below.

Adidas conducts an initial assessment, which consists of a

document check whereby prospective suppliers are assessed against the Workplace Standards

(discussed below) and may include a factory visit. As stated in Adidas’ Enforcement Guidelines,

Adidas checks prospective suppliers against a set of zero tolerance issues

(e.g. prison labour, repetitive and systematic abuse, life-threatening health

and safety conditions)[12]

and threshold issues (e.g. fraud and exploitation issues, serious labour

issues).[13] Zero

tolerance issues are severe breaches that ‘may threaten the lives or well-being

of workers, suppress fundamental rights, or result in irreparable damage to the

environment’, whereas threshold issues are ‘those types of breaches or

workplace issues which are considered to be extremely serious in nature,

requiring enforcement action to be taken against existing suppliers.’[14]

Where a zero tolerance issue exists, Adidas will reject a

relationship with that particular prospective supplier, whereas where a

threshold issue exists, if the issue can be fixed, a prospective supplier will

be given a timeline to rectify the issues. If they are found to have improved

after a subsequent check, they will be approved.[15] In 2018, Adidas conducted initial assessments of

221 factories. As a result, approximately 25% were rejected directly after the

initial assessment due to the presence of zero tolerance issues or after a

second visit due to the presence of threshold issues that they failed to

rectify between the initial and subsequent visits.[16]

With respect to Adidas’

indirect supply chain, external audit firms are commissioned to carry out

initial assessments. Adidas provides detailed guidance to these external

monitors so that assessments are carried out in a consistent manner. Where

these assessments identify the need for remediation processes, the SEA team

oversees them.[17]

Once a supplier, agent,

licensee or subcontract has been approved, they enter into a formal legal

agreement (e.g. manufacturing agreement). Adidas’ Workplace

Standards are an integral part of such agreements

– parties are contractually bound to uphold the Workplace Standards and act in

a manner that safeguards human rights, workers’ employment rights, safety and

the environment. They are also required to assist in identifying issues as and

when they arise.[18]

Suppliers are encouraged to share the Workplace Standards with their

subordinate relationships, including external service providers. Additionally,

Adidas incorporates human rights-related clauses into its direct supplier

contracts, as well as clauses relating to labour, workplace health and safety

and the environment.

Engaging with existing suppliers

Once direct suppliers have

been approved and have entered into a contractual relationship with Adidas,

Adidas monitors their compliance through auditing, factory visits, worker

feedback mechanisms, partnerships with external organisations (such as ILO

Better Work, the Bangladesh Accord and the Fair Labor Association) and

stakeholder outreach, including engagement with government regulators, unions,

employer federations, workers and civil society groups at the country level.

This process enables Adidas to monitor its supply chain risk to ensure that its

suppliers manufacture in a socially and environmentally responsible manner.[19]

The CRAs that Adidas

conducts results in the categorisation of countries as either high or low risk,

factories located in high-risk countries are more likely to be audited regularly

(the full list of countries by category is not publicly available). Factories

located in low-risk countries are excluded from Adidas’ audit coverage.[20] Factories are assessed based

on their commitment to and performance against the Workplace

Standards. During 2018, Adidas conducted 546

factory visits in order to engage to ‘improve working conditions and … empower

workers’[21],

and 1,207 social compliance audits and environment assessments. Additionally,

for suppliers that were considered to be ‘compliance mature’ 102

self-governance audits and collaboration audits were conducted, which were

reviewed by Adidas.

Where non-compliances

are identified, if the relevant issue is a zero tolerance issue a warning and

potential disqualification of a supplier will be triggered. If the relevant

issue is a threshold issue, Adidas will see whether the issue can be addressed

in a specified timeframe through remedial action. It may also take enforcement

action against the supplier, which includes the termination of the

relationship, stop-work notices, third party investigations and warning

letters. In 2018, Adidas issued a total of 39

warning letters across 16 countries, and terminated agreements with

one supplier on the basis that it refused to grant the SEA team

access to audit the factory.[22]

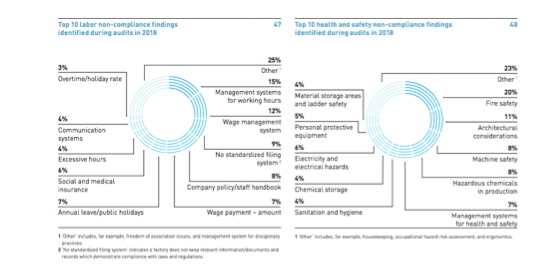

The top 10 labour and health and safety non-compliance findings

during the 2018 audits are depicted in the image below.

Source: Adidas Annual

Report 2018, p 99.

External monitors that have been approved by Adidas audit indirect supply chain

factories that work with Adidas’ licensees and agents. Audits are conducted at

least once a year, but will be conducted more frequently when additional follow

up assessments are required to monitor remedial action.

Adidas has also

implemented a Crisis Protocol so that business entities and factories can

report on high-risk issues, which in turn inform Adidas’ site visits, audits

and engagement with the business entities and factories.[23]

Stakeholder Engagement Channels

Adidas’ Stakeholder

Relations Guidelines define its stakeholders as ‘those

people or organizations who affect, or are affected by, [its] operations and

activities.’ Its stakeholders include employees, shareholders and investors,

authorisers (e.g. governments and trade associations), business partners (e.g.

unions and suppliers), workers in supplier factories, customers and

opinion-formers (e.g. journalists and special interest groups). Adidas claims

to utilise stakeholder engagement in order to identify human rights risks and

impacts through its supply chains. In order to obtain the views of these

different stakeholders, frequent forms of engagement utilised by Adidas include

stakeholder consultation meetings with workers, NGOs and suppliers, meetings

with investors and Socially Responsible Investment analysts, employee

engagement surveys and programmes, responding to inquiries from consumers and

the media and participating in multi-stakeholders initiatives (e.g. the Better

Cotton Initiative). Adidas aims to ensure that its engagement is balanced and

inclusive.

Adidas captures and

addresses complaints from third parties through its third

party grievance mechanism. The mechanism allows third parties directly

affected by an issue, including workers within its supply chains, to raise

complaints. Complaints may be raised in relation to violations of Adidas’ Workplace

Standards, or any potential, or actual, breach of

human rights linked to Adidas’ operations, products or services. As part of

this, Adidas also has an SMS hotline in the countries in which it sources its

products so that workers can voice their concerns in an easy manner. From 2014

to 2018, Adidas has received a total of 52

complaints relating to labour and human right

concerns by third parties. Third parties may also lodge complaints through the Third

Party Complaint Process of the Fair Labor Association and the OECD National

Contact Point for Germany.

Additionally, Adidas’

SEA Team regularly meets and interviews supply chain workers and tracks

feedback from independent worker hotlines and from its suppliers’ own internal

complaint systems.

Identified risks

Through the processes

set out above Adidas has identified various human rights risks in its supply

chains. Salient human rights risks include: freedom of association and

collective bargaining, working hours, health and safety, fair wages, child

labor, forced labor, resource consumption, water (including chemical

management), access to grievance mechanisms, diversity, mega sporting events,

procurement, product safety, as well as data protection and privacy security.

Other risks identified include right of assembly, freedom of

expression, migrant workers, human trafficking, discrimination, Indigenous

peoples’ rights, occupational health and safety and environmental pollution.[24]

A number of these risks are common to the garment and footwear industry as

noted by the OECD

Guideline on Responsible Supply Chains in the Garment and Footwear Industry.

Integrating and Acting

Adidas feeds the findings from the identification and assessment

processes set out above into its active programmes and they drive prevention

and mitigation measures.

The SEA Team reports

risks identified in Adidas’ supply chains to executive management on a monthly

basis.[25] Reporting highlights the

critical issues, investigations and remedial efforts taken with respect to

Adidas’ direct and indirect supply chains. This is the ‘primary vehicle

through which human rights concerns are shared with senior management and

reported progress is tracked’.

Where adverse human rights impacts occur, Adidas seeks to

remediate those cases. Corrective Action Plans (CAPs) are put in place, which

set out the remedial action, the responsible party and a timeframe to complete

that action. The supplier’s specific proposals in the CAP are then tracked and

the appropriate documentation, or remedial action(s), reviewed to close-out the

non-compliances. CAPs are normally developed through engagement with the

suppliers, to define expectations and negotiate appropriate timelines.[26] The SEA Team closely monitors the development and implementation of CAPs through

follow-up audits and record progress and verification status.

In the past, Adidas has examined and remediated instances of ‘forced

labour, child labour, freedom of association, right of assembly, freedom of

expression, discrimination, indigenous people’s rights, occupational

health and safety, resource consumption and environmental pollution’.[27]

It has also dealt with specific cases where workers have been subject to

arbitrary arrest and detention and reached out to judicial authorities where

human rights defenders have also faced arrest and detention for supporting

worker’s rights. It has petitioned governments for their failures in

enforcement, particularly in relation to the right to form and join trade

unions and the upholding of statutory minimum wages.[28]

In order to prevent adverse human rights impacts from occurring,

Adidas binds its suppliers to its Workplace Standards. It continuously monitors

those suppliers in which it has a direct contractual relationship and assesses

their performance against the Workplace Standards. Adidas also engages in

capacity building to strengthen its suppliers’ internal governance and

management systems in order to reduce the potential for adverse human rights

impacts. With respect to its indirect supply chain, Adidas places expectations

on its primary business partners to engage and apply its Workplace Standards.

With respect to

grievances raised, in cases where Adidas has caused or directly contributed to

the violation, it will seek to prevent or mitigate the chance of the impact

occurring or recurring. If an adverse impact is occurring, Adidas will engage

actively in its remediation – this may involve site visits, audits or other

engagement with a business entity or factory.[29] Where Adidas has neither

caused nor directly contributed to a violation, it will encourage the business

entity that has caused or contributed to the impact to prevent or mitigate its

recurrence.

Tracking

Adidas monitors and evaluates the effectiveness of its response to

human rights risks and impacts.

Adidas’

Internal Audit team conducts periodic assessments to evaluate the effectiveness

of individual departments and programs, with defined timelines for corrective

actions. It reports directly to the CEO and Supervisory Board. As part of this,

it evaluates the effectiveness of Adidas’ social compliance monitoring system

and human rights due diligence processes and their alignment with policy

commitments.

Adidas’

social compliance program is subject to annual third party audits and public

disclosure of tracking charts by the Fair Labor Association (available here), to determine

whether supplier-level remediation is being effectively managed by Adidas. The

Fair Labor Association also undertakes a periodic accreditation process whereby

it evaluates all elements of Adidas’ labour and human rights work.[30]

For its direct supply

chain, Adidas utilises social and environmental KPIs to assess the

effectiveness of its suppliers’ systems to protect labour rights, worker safety

and the environment. For its licensee partners and agents that manage its

indirect supply chain, Adidas uses a scorecard that evaluates and scores a

business entities performance in applying its Workplace Standards and

associated guidelines. KPIs and scorecards assist Adidas to determine strategic

suppliers and influence sourcing decisions. However, it is unclear as to how

KPIs and scorecards influence such decisions and the extent to which they do

so. Further, both factories and business entities and licensees are required to

prepare strategic compliance plans on a regular basis outlining their

strategies to meet Adidas’ Workplace Standards. Adidas’ SEA team uses these

plans to monitor the commitment and compliance practices of its direct and

indirect supply chains.[31]

Communicating

Adidas claims to have regular contact with

a diverse range of stakeholders, including vulnerable groups, workers in supply

chains, local and international NGOs, labour rights

advocacy groups, human rights advocacy groups, trade unions, investors,

national and international government agencies, and academics. The stakeholders

that Adidas engages with depend on the specific issues and trends at the time.

It uses its network to pinpoint areas for dialogue and the applicable parties

to engage with. It then prioritises stakeholders depending on action radius,

relevance, risk, willingness and capacity to engage. The frequency of dialogue

can range from monthly to quarterly or annually.

Adidas utilises various channels to

communicate its human rights impacts, policies and approaches, including:

- annual Sustainability Progress Report;

- annual Modern Slavery Statements;

- individual stakeholder meetings and

correspondence;

- structured stakeholder dialogues;

- public statements;

- collaborative engagements with NGOs;

- multi-stakeholder and partner organizations; and

- one-on-one worker interviews and meetings.

It also uses FAQs and blogs, as an accessible and understandable

way for the public and its internal staff, to grasp its human rights work and

specific programme initiatives related to worker rights, safety and the

environment.[32]

Other vehicles for stakeholder engagement include purpose-built fora such as

the OECD Advisory Panel for

embedding of Business & Human Rights Due Diligence practices into the

Apparel and Footwear sector, the Bali Process Business and Government Forum and

the Bangladesh Accord.[33]

Adidas seeks to define and tailor the appropriate level of

communications needed for a given target audience. For example, with respect to

trade unions, it is Adidas standard protocol that its local monitoring staff

engage with the factory-level trade union officials or relevant worker

representatives to cross check issues that arise during its compliance audits

and discuss the necessary remedial actions that the supplier has to follow-up

on.

To ensure clear and effective communications with local stakeholders,

affected communities and other vulnerable groups, the SEA Team has embedded

local staff in Adidas’ key sourcing countries. The team operates in 18

languages, but employs translators where needed for special investigations,

stakeholder outreach or communicating outcomes or mechanisms to improve human

rights impacts. For example, Adidas has contracted Arabic translators in Turkey

to support its communications with Syrian refugees at risk of exploitation in

the supply chain. With respect to complaints, phone calls and direct

face-to-face meetings will be used to capture issues and provide feedback. Adidas

publishes high-level information regarding the status and resolution of

complaints through its third party grievance mechanism on its website (see, for

example, a summary of the third party complaints handled by Adidas in 2018 here).

The Gaps Between Paper and Practice

As stated at the outset, brands within the

apparel and footwear sector face a plethora of challenges in conducting

effective HRDD given the human rights risks inherent in their supply chains.

Adidas itself has acknowledged

that effective HRDD remains a ‘primary challenge’ of the business, given the

‘breadth and depth of [its] business, which includes tens of thousands of

business relationships along a value chain that stretches from smallholders,

farming cotton, to the final point of sale in a retail store.’ Nonetheless,

Adidas is considered to have leading HRDD practices globally, not only in the

apparel sector, but also across the sectors that have been benchmarked to date.[34]

What is clear from a review of Adidas’ human

rights approach is that it recognises its responsibility to respect human

rights and has sought to take steps to fulfil this obligation along its entire

value chain. As part of that, it has developed over a period of over 20 years

extensive HRDD practices fleshing out its commitment to upholding human rights.[35]

Adidas’ HRDD practices seek to properly identify and assess the human rights

risks and impacts that arise in its supply chains, and prevent and mitigate

those risks through engagement with suppliers and stakeholders.

Despite this strong commitment and

extensive HRDD processes and procedures in its supply chains, Adidas’ human

rights track record is not perfect. Over recent years Adidas has featured in

headlines where it has been demonstrated that human rights issues exist in its

supply chains. Many of these issues relate to the wages paid to its supply

chain workers. In 2014, the Clean Clothes

Campaign (CCC) released a profile

on Adidas with respect to its practices regarding workers’ living wages. The

profile noted that while Adidas was assessing its wages practices across Asia,

‘it [was] still not willing to define what a living wage means in its business’

and had passed on responsibility for wages in supplier factories to factory

owners. The CCC called on Adidas to ‘engage in identifying a living-wage figure

and changing pricing in order to enable its payment.’ This call to action came

after workers in factories that supply to Adidas went on strike in Asia.

In 2014, there was a nationwide

strike in Cambodia calling for an increase of the minimum wage for garment

workers. Shortly before the strike the CCC reported that the minimum wage in

Cambodia at the time did not allow workers to meet their living costs in

housing, food, clothing, education, transport and healthcare. During a

crackdown in Cambodia, five workers were shot dead and 30 others were injured.

Following this event, Adidas backed

the development of a minimum wage review mechanism for garment workers.

Also in 2014, workers at the Yue Yuen shoe factory in China, an Adidas supplier,

went on strike

over social security payments and housing fund contributions. In response, Adidas

moved some of its orders from the factory in order to ‘minimize the impact on

[its] operations’. It did not sever ties with the factory given that ‘China is,

and will continue to be, a strategic sourcing country for [it].’ Again in 2015

workers from the same factory went on strike

due to changes in its production process, resulting in workers demanding an

immediate payout of their housing fund. No information on Adidas’ response to

this issue has been located, however, Reuters reported

that Adidas did not immediately respond to its request for comment.

The payment of low wages to workers was

more recently raised in June last year where Adidas was accused of ‘foul play’ by paying thousands of female

workers within its supply chain low wages in order to prepare football shirts

and shoes for the Football World Cup that year. In their report,

Éthique sur l’étiquette and the CCC

compared the costs of Adidas’ current production with that in the 1990s and

found that the costs paid to workers had decreased by 30%. Noting that a large

proportion of Adidas production occurs in Indonesia, it found that the wages

paid to female workers was not sufficient to cover their basic needs, with some

women not even receiving the minimum legal wage. The report stated that:

If … Adidas had

paid the same amount of dividends in 2017 as they did in 2012, or maintained

the level of marketing/sponsorship spending, the resulting proceeds would have

allowed for living wages to be paid throughout their entire supply chain in

China, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Cambodia.

Outside Asia, concerns were also raised in

2016 in relation to the treatment

and serious exploitation of Syrian refugees in Turkish supplier factories,

including sexual abuse and child labour. As a result, Adidas was called upon by

the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre to respond to these concerns by

completing a questionnaire, Adidas’ response

to the questionnaire outlined its policies and procedures with respect to

employing Syrian refugees and their treatment in supply chains, noting that it

does not have any Syrian refugees working for any of its five Turkish first

tier Turkish suppliers.

Similarly concerns were also raised in 2016

and 2017 in relation to the poor working conditions in shoe supply chains in

Eastern Europe (see for example the CCC’s reports titled ‘Labour

on a Shoe String’ and ‘Europe’s

Sweatshops: The results of CCC’s Most Recent Researches in Central, East and

South East Europe’). Adidas was again called upon by the Business and Human

Rights Resource Centre to respond to a series of questions regarding its

efforts and work in the area of sustainability and social responsibility,

precisely on sourcing policies with regard to Eastern Europe. In its 2016

response, Adidas defended its engagement with leather tanneries stating

that it has ‘a well-tested human rights due diligence process, one which

considers the severity of country and industry-level risks within our global

supply chain.’ However, it also noted that the sourcing of raw hides and

finished leather has been identified as a ‘priority area for further assessment

and [its] deeper involvement’. With respect to its footwear manufacturing in

Eastern Europe, Adidas stated that ‘more should be done to improve wages’ and

‘engagement between local suppliers, unions, governments, and buyers’ is

critical to improving the lives of workers. It did not, however, outline what

actions it would take to improve worker wages. In its 2017

response, Adidas set out its general approach to ensuring fair wages in its

supply chain and provided an example of the processes it has followed to set

wages in Georgia and the Ukraine.

Conclusion

The instances of human / labour rights

abuses detailed above demonstrate that despite Adidas’ comprehensive HRDD

process, there are failings and gaps in that process that create space for

human rights violations to occur in its supply chains. It also shows that the

paper-based process detailed in this blog has imperfections in practice that

need to be ironed out. Literature has demonstrated that there are often

considerable discrepancies between HRDD processes on paper and in practice,

highlighting gaps in supply chain governance. For example, Genevieve LeBaron has

found

through her research on ethical audits and the supply chains of corporations,

businesses have ‘claimed supply chain monitoring for themselves’ by using

audits as a way to ‘preserve their business model and take responsibility for

supply-chain monitoring out of the hands of governments.’ As such, they have

been able to avoid ‘stricter state and international regulation’ and to take

steps to ensure they are perceived as responsible companies. However, while

this is benefiting businesses by giving the impression that businesses are

taking active steps on the journey to respect human rights, it is failing

workers in supply chains. Human rights violations such as labour abuses are

still widespread within supply chains. Therefore, in order to avoid going down

this path, businesses need to engage with the issues that are arising in their supply

chains, consider the root causes of those issues and make adjustments to HRDD

processes.

This review of Adidas’ HRDD process and the

gaps identified between the process in theory and in practice raises a number

of interesting questions. For example – What precise aspects of Adidas’ identification

of risks process are not living up to their expectations allowing human rights

violations to continue to occur in its supply chains? What steps are Adidas

taking in order to continuously improve its HRDD process? To what extent does

Adidas look to or gain inspiration from the practices of its peers? What

challenges does Adidas currently face in conducting HRDD in its supply chains

and how is it seeking to respond to those challenges?

[4] Adidas Annual

Report 2018, p 72.

[5] Adidas Profile.

[6] Adidas Supply

Chain Approach.

[7] Adidas Assessment

for Re-Accreditation by the Fair Labor Association, p 6.

[8] Adidas Supply

Chain Approach.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Adidas Sustainability

Report 2010, p 42

[20] Adidas Annual

Report 2018, p

98

[26] Adidas Response

to KnownTheChain Apparel and Footwear Benchmark, p 16.

[27] Business and Human Rights Resource Centre, Company Action Platform,

Adidas.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Adidas Supply

Chain Approach.

[30] Adidas was

last re-accredited in 2017.

[31] Adidas Sustainability

Report 2010, p

49

[32] See for

example Adidas’ Human Rights and Responsible

Business Practices: Frequently Asked Questions.

[33] Adidas Analysis:

Cross Section of Stakeholder Feedback 2017/2018.