Editor’s

note: Shamistha Selvaratnam is a LLM Candidate of the Advanced Masters of

European and International Human Rights Law at Leiden University in the

Netherlands and a contributor to the Doing

Business Right project of the Asser Institute. Prior to commencing the LLM, she worked as a business and human

rights solicitor in Australia where she specialised in promoting business

respect for human rights through engagement with policy, law and practice.

Human right due diligence (HRDD) is a key

concept of Pillar 2 of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights

(UNGPs), the corporate responsibility to respect human rights. Principle 15 of

the UNGPs, one of the foundational principles of Pillar 2, states that in order

to meet the responsibility to respect human rights, businesses should have in

place a HRDD process to ‘identify, prevent, mitigate and account for how they

address their impacts on human rights’. However, how was the concept of HRDD

developed? What does it mean? What are its key elements?

This first blog of a series of articles

dedicated to HRDD answers these questions by providing an overview of the

concept of HRDD and its main elements (as set out in the UNGPs) as well as how

the concept was developed. It will be followed by a general article looking at

HRDD through the lens of a variety of actors including international

organisations, non-state actors and consultancy organisations. Case studies

will then be undertaken to look at how HRDD has materialised in practice. To

wrap up the series, a final piece will reflect on the effectiveness of the turn

to HRDD to strengthen respect of human rights by businesses.

History

of the Concept of HRDD

The concept of due diligence was around

well before John Ruggie assumed the mandate of Special Representative on the issue

of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises

back in 2005. Indeed the concept was initially a creature of American

securities law under the auspices of ‘reasonable investigation’. The Securities Act 1933 imposes strict civil

liability on certain people for untrue statements and omissions of material

fact in a securities registration statement.[1]

However, an exception is carved out where ‘reasonable investigations’ have been

undertaken.[2] The relevant standard of

reasonableness to be applied in this situation is that of a ‘prudent man in the

management of his own property’.[3]

Following this, the concept of due

diligence emerged in other corporate contexts, particularly with respect to

financial transactions such as mergers and acquisitions.[4]

While the due diligence carried out on such transactions in the 1980s was quite

limited, the process has gradually become much more extensive. Over time, the

concept has been transplanted into the international human rights law framework

– a positive duty has been imposed on states to conduct due diligence to

prevent human rights violations by non-state actors, including businesses.[5]

Thus, in the international human rights law arena due diligence has been

applied as a standard of conduct that states are required to meet in order to

uphold human rights within their jurisdiction.

In the business and human rights sphere,

the concept of due diligence was first introduced back in 2003 when the draft Norms on the Responsibilities of Transnational

Corporations and Other Business Enterprises with Regard to Human Rights

(draft Norms) were introduced.

Article 1 of the draft Norms placed a primary responsibility on states to

ensure that businesses respect human rights. It also placed a separate

obligation on businesses ‘to promote, secure the fulfillment of, respect,

ensure respect of and protect human rights recognized in international as well

as national law’ within their sphere of influence. The commentary to

article 1 notes that businesses have the responsibility to use ‘due diligence

in ensuring that their activities do not contribute directly or indirectly to

human rights abuses, and that they do not directly or indirectly benefit from

abuses of which they were aware or ought to have been aware’. No further

explanation was provided on the due diligence to be conducted and the draft

Norms were not approved by the Human Rights Council in 2004.

The concept of due diligence was brought

back into the business and human rights arena when Ruggie was appointed as

Special Representative. Following

the failure of the draft Norms, Ruggie introduced the concept of HRDD back into the

international arena in 2008 and developed it over a period of about three years

until the UNGPs were endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council. As he acknowledges, until then due diligence was considered a ‘business

process’ used in ‘strictly transactional terms’.[6]

However, Ruggie sought to broaden the concept into ‘a comprehensive, proactive attempt to uncover

human rights risks, actual and potential, over the entire life cycle of a

project or business activity, with the aim of avoiding and mitigating those

risks.’[7]

He did this by drawing on the key elements of due diligence and combining them

with the distinctive elements of human rights. This is what is now referred to

and articulated as the concept of HRDD in the UNGPs. Ruggie gave HRDD such a

key role in Pillar 2 of the UNGPs because he recognised that companies cannot know

or show that they are respecting human rights without conducting HRDD.[8]

Indeed, he envisioned that HRDD would facilitate movement from ‘naming and

shaming’ businesses by external stakeholders to ‘knowing and showing’ through

internalising respect for human rights.[9]

Ruggie

identified a number of benefits to business for undertaking HRDD, in particular

he highlighted that it wouldn’t impose additional burdens on business.[10]

He argued that HRDD assists business to ‘address their responsibilities to

individuals and communities that they impact and their responsibilities to shareholders,

thereby protecting both values and value’.[11]

He further acknowledged that HRDD assists companies to lower their risks,

particularly with respect to legal non-compliance.[12]

He also noted that conducting HRDD has the ability to protect Boards against

claims brought by shareholders regarding mismanagement.[13]

In setting

out the scope of HRDD, Ruggie stated that it is to be ‘determined by the context in which a company is operating, its activities, and the

relationships associated with those activities’[14]

by reference to three factors, namely: (a) the country and local context in

which the relevant business activities take place; (b) what human rights

impacts the business’ own activities may have within that context; and (c)

whether the business’ own activities might contribute to abuse through the

relationships connected to their activities.[15]

Importantly, he noted that the scope of HRDD is not fixed or based on

influence, rather it ‘depends on the potential and actual human rights

impacts resulting from a company’s business activities and the relationships

connected to those activities’.[16]

With respect to the substantive content of HRDD, John Ruggie stated that

the minimum requirements are set out in the International Bill of Human Rights

and the ILO core conventions, as well as additional standards relevant to the

context of a particular business such as international humanitarian law.[17]

As to the HRDD process itself, Ruggie set out four minimum requirements.

Businesses should:[18]

- Adopt a human rights policy.

- Conduct human rights impact assessments to ‘understand how existing and proposed

activities may affect human rights’.

- Integrate human rights policies through

the business, which requires a top down approach in order to ‘embed respect for

human rights throughout a company’ as well as training and the ‘capacity to

respond appropriately when unforeseen situations arise’.

- Track their performance through

monitoring and auditing processes with regular updates of human rights impact

and performance.

Following these developments, the HRDD

concept was finally articulated in the UNGPs, which were endorsed by the UN

General Assembly in 2011.

Concept

of HRDD as articulated in the UNGPs

Meaning of HRDD and its Scope

Despite being a key element of the UNGPs,

HRDD is not defined in the UNGPs itself. Rather, as stated above, the UNGPs states

that HRDD is a process – that is, a process that should ‘identify,

prevent, mitigate and account for how [businesses] address their impacts on

human rights’. However, in interpretative guidance provided by the Office of

the High Commissioner of Human Rights, due diligence is defined as follows:[19]

such a measure of prudence, activity, or assiduity, as is properly to be

expected from, and ordinarily exercised by, a reasonable and prudent [person]

under the particular circumstances; not measured by any absolute standard, but

depending on the relative facts of the special case”. In the context of the

Guiding Principles, human rights due diligence comprises an ongoing

management process that a reasonable and prudent enterprise needs to undertake,

in the light of its circumstances (including sector, operating context, size

and similar factors) to meet its responsibility to respect human rights.

(Emphasis added)

It is clear from the definition above that HRDD

is separate to the due diligence processes generally carried out by a business

(for example, corporate due diligence). It is also clear that HRDD should be

undertaken by all businesses in order to respect human rights. However, the

extent of the HRDD to be carried out is dependent on various factors. As stated

in Principle 17, the scope of HRDD is dependent on the ‘size of the business

enterprise, the risk of severe human rights impacts, and the nature and context

of its operations’. Accordingly, the scope of HRDD processes should be tailored

to a specific business’ needs and should evolve as a business’ operations and

operating context develop – therefore, the process that is applied by one

business cannot necessarily be applied by another business. For example, larger

businesses are required to carry out more extensive HRDD than smaller

businesses.

Elements of HRDD

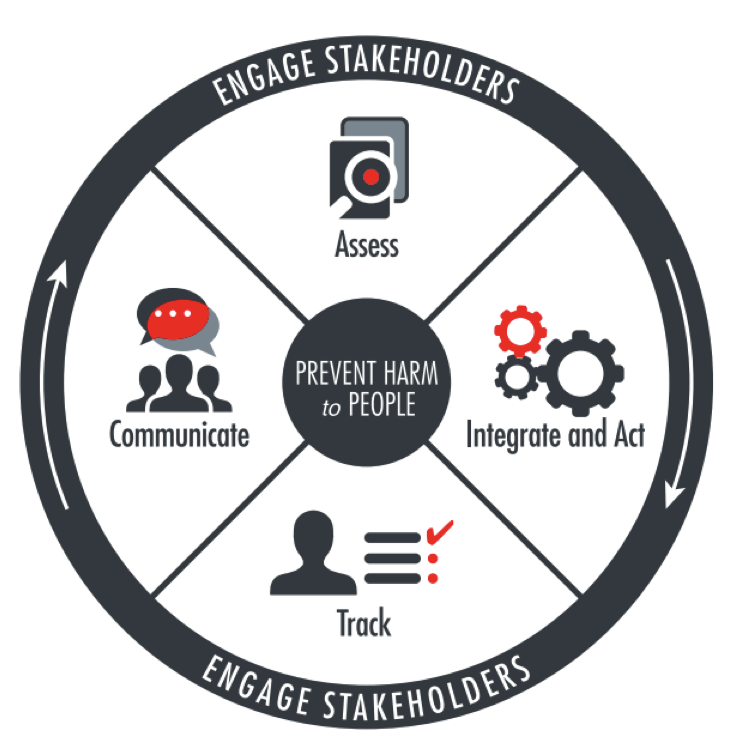

The four key interrelated elements of HRDD

are set out in Principles 18 to 21 of the UNGPs, namely, assessing actual or

potential adverse human rights impacts, integrating findings across the

business and taking appropriate action, tracking the effectiveness of their

response and communicating with stakeholders. This process will be explained in

further detail below.

In order to conduct HRDD, businesses should

start by conducting regular human rights impact assessment in order to by

identify and assess ‘any actual or potential adverse human rights impacts which

they may be involved’ in both their activities as well as their business

relationships. Such an assessment is a critical aspect of HRDD as it is

necessary for a business to evaluate its human rights risks before it can

consider the steps to take to address those risks. The assessments should

involve:[20]

assessing the human

rights context prior to a proposed business activity, where possible;

identifying who may be affected; cataloguing the relevant human rights

standards and issues; and projecting how the proposed activity and associated

business relationships could have adverse human rights impacts on those

identified.

The findings of such assessments should

then be integrated across a business’ relevant internal functions and processes

to prevent and mitigate risks identified. Further, action should be taken where

the business has had actual impacts so as to remediate those affected.

Complexities may arise with respect to this element of HRDD, with

situations existing where a business may not contribute to an adverse human

rights impact, but nevertheless because of the business’ relationship with a

third party the impact is directly linked to the business’ operations, products

or services. Situations may also exist where a business has little or no

leverage to address an impact. In such situations, businesses should seek

independent expert advice.[21]

Businesses should then track the effectiveness of

their response to adverse human rights impacts. Tracking allows a business to

ensure that it is appropriately and adequately addressing the human rights

impacts of its operations and to adapt its response if required. It should be

‘based on appropriate qualitative and quantitative indicators’ and ‘draw on

feedback from both internal and external sources’.

The approach taken by businesses to address

their human rights impacts should be communicated externally, including to

those affected. Where severe human rights impacts exist within a business, how

the business responds to impacts should be reported in a formal manner. In

order to ensure that useful information is provided to external stakeholders,

all communications should be accessible to its intended audience and provide

sufficient information to ensure that business’ can evaluate the adequacy of

their response to a particular human rights impact involved. Such communication

ensures accountability and transparency on the part of the business.

The image below developed by Shift illustrates

the cyclical nature of the HRDD process and shows that it is an ongoing process

that must be undertaken in regular intervals in order to truly assist

businesses to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for how they address

their impacts on human rights.

Conclusion

As discussed above, HRDD lies at the heart of

the corporate responsibility to respect human rights in the UNGPs. While the

UNGPs were released in 2011, the concept of due diligence was around almost two

decades before that – however, it was applied purely in the context of

commercial transactions. The draft Norms imported the idea of due diligence

into the business and human rights sphere. After the draft Norms failed, Ruggie

revived the concept when he was appointed as Special Representative. He saw

HRDD as key to businesses being able to know and show that they respect human

rights to their stakeholders. Ruggie developed the concept from 2005 onwards, emphasising

its benefits for businesses. Leading to the final articulation of HRDD as a

central mechanism of the UNGPs in 2011.

From the discussion in this blog post, it

is clear that the UNGPs as well as Ruggie’s reports and statements in the lead

up to their inception do not (and probably could not) explicitly address how

HRDD is to be applied and operationalised by businesses in practice. This will

be explored in greater detail in the upcoming blog posts in this series.

[9] Keynote

Address by SRSG John Ruggie “Engaging Business: Addressing Respect for Human

Rights” (2010).

[10] Ibid.

[12] Keynote

Address by SRSG John Ruggie “Engaging Business: Addressing Respect for Human

Rights” (2010).