Editor's Note: Frans M. de Weger is legal counsel

for the Federation of Dutch Professional Football Clubs (FBO) and CAS

arbitrator. De Weger is author of the book “The

Jurisprudence of the FIFA Dispute Resolution Chamber”, 2nd

edition, published by T.M.C. Asser Press in 2016. Frank John

Vrolijk specialises in Sports, Labour and Company Law and is a former legal

trainee of FBO and DRC Database.

In this first blog, we will try to answer some questions raised in

relation to the Article 12bis procedure on overdue payables based on the

jurisprudence of the DRC and the PSC during the last two years: from 1 April

2015 until 1 April 2017.

[1] The awards of the Court of

Arbitration for Sport (hereinafter: “the CAS”) in relation to Article 12bis

that are published on CAS’s website will also be brought to the reader’s

attention. In the second blog, we will focus specifically on the sanctions applied

by FIFA under Article 12bis. In addition, explanatory guidelines will be

offered covering the sanctions imposed during the period surveyed. A more

extensive version of both blogs is pending for publication with the

International Sports Law Journal (ISLJ). If necessary, and for a more detailed

and extensive analysis at certain points, we will make reference to this more

extensive article in the ISLJ.

In 2015, FIFA announced a very significant addition to the Regulations

on the Status and Transfer of

Players (hereinafter: “the RSTP”): the inclusion of a new

provision on overdue payables by defaulting clubs towards players and other clubs.

On 1 April 2015, the 2015 edition of the RSTP gave birth to a fast-track

procedure to deal with overdue payables enshrined in Article 12bis

(hereinafter: “the 12bis procedure”). In its Circular letter no.

1468, FIFA also strongly urged all of its member associations

to make sure that their affiliated clubs were informed of this new provision

immediately.

From Article 12bis,

which is also laid down in the 2016 edition of the RSTP, it follows that clubs

are required to comply with their financial obligations towards players and

other clubs as per the terms stipulated in the contracts signed with their

professional players and in the transfer agreements signed with other clubs. In

accordance with Article 12bis FIFA is entitled to sanction clubs that have

delayed a due payment for more than 30 days without a prima facie contractual

basis.

It was a real thorn

in the side of FIFA that too many clubs, on a worldwide level, did not comply

with their financial contractual obligations without legitimate reasons.[2] With the introduction of

this provision, it was not only FIFA’s aim to continue its process to further

speed up its proceedings, but also to establish a stronger system regarding

overdue payables towards players and clubs. FIFA stressed that it

wanted to further improve efficiency and provide

clear regulatory steps to deal with overdue payables from clubs to players and

from clubs to other clubs.

As from 1 April

2015, the Dispute Resolution Chamber (hereinafter: “the DRC”) and the Players’

Status Committee (hereinafter: “the PSC”) are FIFA’s competent authorities to

deal with claims on overdue payables in relation to Article 12bis. Both FIFA committees

were given a wide scope of discretion to impose sanctions on defaulting clubs,

such as fines and transfer bans. In fact, the possibility to impose sanctions is

critical to support a stronger and more efficient dispute resolution system regarding

overdue payables, as we will see in the second blog.

The introduction of

FIFA’s 12bis procedure also gave rise to many (legal) questions. For example, are

only clubs and players entitled to lodge a claim before respectively the PSC

and the DRC? Or are other parties, such as coaches and national associations, also

entitled to raise their claims under 12bis? Do claims for training compensation

and solidarity contribution fall under 12bis? Can the 12bis procedures be

considered as a real fast-track procedure? Under what circumstances can an

offence be considered a repeated offence? And also, since the imposition of

sanctions is key to the efficacy of the 12bis procedure, under what conditions

will these sanctions be imposed? These are only a small sample of the questions

that arose after the introduction of the 12bis procedure. In this first blog, we

will try to answer the most important questions raised based on the

jurisprudence of the DRC, PSC and CAS.

General preliminary observations

As a starting point, it

must be noted that exactly 137 decisions by the DRC and the PSC regarding

Article 12bis have been published by FIFA on its website between 1 April 2015

and 1 April 2017.[3]

Of these 137 decisions, 99 decisions have been dealt with by the DRC, including

58 decisions issued by the DRC Single Judge. Additionally, 32 decisions were

passed by a Chamber of three judges, whereas 24 of these decisions were passed

by circulars and eight were passed by a decision of a sitting Chamber in

Zürich, Switzerland. Only nine FIFA decisions were passed by a Chamber of five

judges.

From the 38 decisions of

the PSC, 37 were issued by its Single Judge and only one[4] was issued by a Chamber of

three judges via a circular. It can be noticed that in most “renouncement of

right cases” (in which defaulting clubs have not replied to the claim of the

claimant party), a Single Judge has dealt with the case.

Analysing the decisions,

it is striking that all claimants in the 137 decisions won their cases. In

other words, in none of the decisions of the DRC and the PSC it was found that

a “prima facie contractual basis”

existed for the respondent party, which would justify non-compliance with the

original contract. A sanction was imposed in all decisions.

It can further be

observed that in the great majority of the decisions, the respondent party did

not reply to the claim. As we will see, the absence of a reply will generally

result in more severe 12bis sanctions for the defaulting club.

The jurisprudence of FIFA

also illustrates that the 12bis procedure are a step towards swifter

proceedings. In the last

years we have already noted a positive development with regard to the length of

‘regular’ proceedings before FIFA (not including the 12bis procedures). With

regard to the 12bis procedure, FIFA stressed that it

has shortened the timeframe for decisions taken on overdue payables, with

decisions now being taken within eight weeks and claimants being notified of a

decision within nine weeks of lodging their complete claim. After analysing the 12bis

decisions of the DRC and the PSC, it is clear that FIFA actually lived up to

these expectations. The average duration of a 12bis procedure is two months. It

is only exceptionally that a 12bis decision lasted longer (four or ultimately

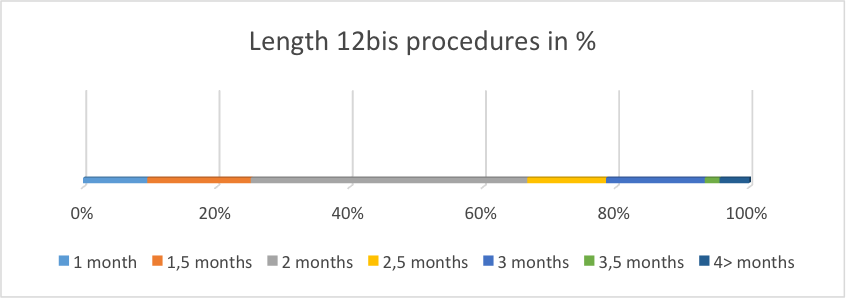

five months) or even took less time (one or one and a half months).[5] As illustrated in Figure

1, approximately 67% of the PSC and the DRC procedures were concluded within

eight weeks. Approximately 80% of both FIFA decisions were dealt with within 10

weeks.

Figure 1

The scope of Article 12bis

The two years of

jurisprudence show that the personal scope of Article 12bis must be interpreted

strictly. As follows from the text of Article 12bis(3), only players and clubs

are entitled to lodge a claim before FIFA. Put another way, coaches, national

associations and intermediaries do not have standing to sue in the 12bis

procedure. This textual interpretation of the provision is confirmed by the

jurisprudence of the DRC and the PSC. In fact, none of the reviewed decisions of

the DRC or the PSC involved a party who was not

a club or a player.

Additionally, it can be

concluded that claims for training compensation or related to solidarity

mechanism are also excluded from the scope of Article 12bis, as this opportunity

is not provided in the provision. Moreover, the current jurisprudence does not

leave room for any other interpretation. With regard to training compensation

and solidarity mechanism, this means that FIFA gives to “overdue payables” a

different meaning than the UEFA Club Licensing and Financial Fair Play

Regulations, since outstanding amounts for training compensation and solidarity

mechanism are considered by UEFA as overdue payables. The same is true for outstanding

payments due by clubs to other (than player) club employees and debts by clubs to

social/tax authorities; such outstanding amounts will not be considered by FIFA

as ‘overdue’ under Article 12bis.

Generally, the DRC deals

mainly with contracts signed by clubs with professional players. These include

employment contracts but it is to be expected that separate agreements could also

fall under the scope of Article 12bis as long as specific

elements of that separate agreement suggest that it was in fact meant to be

part of the actual employment relationship, as the DRC decided in many other

cases (not being 12bis procedures). This is for example the DRC’s position with

regard to image right contracts.[6] Based

on the jurisprudence reviewed, it follows that termination agreements fall

under the scope of Article 12bis.[7] The PSC will only deal

with transfer agreements, including both transfers on a definite[8] as well as on a temporary

basis[9]. It is to be expected that

agreements between clubs that do not concern the status of players, their

eligibility to participate in organised football, and their transfer between

clubs belonging to different associations, will most likely not fall under

Article 12bis.[10]

Finally, it also follows

from Article 12bis(3) that the creditor (player or club) must have put the

debtor club in default in writing, granting a deadline of at least 10 days to comply

with its financial obligations. Regarding this 10-days deadline, FIFA follows a

strict interpretation, as we will see in the following paragraph.

The existence of an ‘overdue payable’

As follows from the

wording of Article 12bis and the corresponding jurisprudence, two prerequisites

must be met to establish that an overdue payable exists under Article 12bis. First,

the club must have delayed a due payment for more than 30 days without a “prima facie contractual basis”. Second,

the creditor (which is the player or club) must have put the debtor club in

default in writing, granting a deadline of at least 10 days to comply with its

financial obligations. In all the published decisions the FIFA committees verified

that a 10-days deadline had been granted. We can therefore assume that this 10-days

deadline is a prerequisite for the DRC and the PSC to proceed with the claim. Although

Article 12bis is not entirely clear as regards the start of the “10-days

deadline”, the jurisprudence shows that it runs as soon as the 30 days have

elapsed.[11]

Disputes can arise with

regard to the fulfilment of the “10-days deadline”. For example, in the CAS award

of 9 May 2016, the player had filed a statement of claim before the DRC on 25

March 2015 and then sent a letter to the club on 30 March 2015 (i.e. five days after filing a claim at

the DRC) putting the club in default for the overdue payment. The club however

argued that this was a violation of Article 12bis(3) of the RSTP, edition 2015,

as it did not make any legal sense whatsoever to address a default notice to a

party after lodging a claim at FIFA. The

CAS however stated that it was clear that the player had already given the club

ample opportunity (the player stated that it had already provided three

separate notices of default) to fulfil its obligations in conformity with

Article 12bis.[12]

The CAS therefore found it curious that the FIFA administration still requested

the player to issue yet another default notice in such a situation when it was

clear that the player had already given the club many opportunities to fulfil

its obligations. This part of the award is interesting. On the one hand it

shows that (the) FIFA (administration) obliges creditors to send a “10-days

deadline” default letter under all

circumstances, while on the other hand it is to be expected that the CAS

might show more flexibility. Interestingly, in a case before the PSC, the

claimant club put the respondent club in default of payment, starting the 10-days

deadline on the exact same date of the submission. This practice was accepted

by the PSC.[13]

In other words, in order to gain time, claimants might be able to lodge a claim

in front of FIFA before the “10-days deadline” of Article 12bis has passed.

To establish whether

“overdue payables” exist, it is decisive that the “overdue payables” existed after

1 April 2015 (the date on which Article 12bis came into force). This is also

confirmed by the CAS. In its CAS award

of 17 June 2016, the Italian club Pescara referred to the fact that the

agreement between Pescara and the Belgian club Standard Liège was entered into

on 10 July 2012, while Article 12bis did not take effect until 1 April 2015.

Pescara stated that it had no means to know that Article 12bis would be enacted

nearly three years later. The Sole Arbitrator however found it decisive and

stressed that the claim made by Standard Liège was made after 1 April 2015 and

that Standard Liège referred clearly to the overdue payables from Pescara. At

the end, all that matters, according to the CAS, was the existence of overdue

payables at the assessment date and that the assessment date was after 1 April

2015.[14]

For the sake of clarity,

the fact that the DRC and the PSC have decided in 12bis procedures that a

defaulting club must pay to the claimant overdue payables does not touch upon

the question whether the contract has been terminated with just cause. To put it

bluntly, a decision in a 12bis procedure does not justify a unilateral

termination based on Article 14 of the RSTP; no legal connection exists in this

regard. The jurisprudence of the DRC in relation to its ‘regular’ proceedings

(not being 12bis procedures) generally shows that a valid ground for unilateral

termination exists only in case there is outstanding remuneration for a period

of three (or sometimes two) months.[15] This means the existence

of an overdue payable under Article 12bis does not automatically give the claimant

the legal right to unilaterally terminate the contract with the defaulting

club. It should also be noted in this regard that it follows from Article 12bis(9)

that the terms of Article 12bis are without prejudice to the application

of further measures derived from Article 17 RSTP in case of a unilateral

termination of the contractual relationship.

In the second blog we will focus

specifically on the sanctions available to FIFA under Article 12bis and will

provide explanatory guidelines covering the sanctions imposed during the period

surveyed.

[10]

Art. 1(1) RSTP, edition 2016.

[11]

Moreover, parties should be aware that the 30 days deadline will start to run

only after the so-called “grace periods” has passed, which also explicitly

follows from the applicable jurisprudence of FIFA. A grace period can be

considered as the period immediately after the deadline for an obligation

during which the amount due, or other action that would have been taken as a

result of failing to meet the deadline, is waived provided that the obligation

is satisfied during the grace period. See DRC 14 November 2016, no.

11161545-E. Also in “regular” DRC cases so-called “grace periods” are accepted.

See inter alia DRC 6 November 2014,

no. 11141064.

[12] See

CAS 2015/A/4153 Al-Gharafa

SC v. Nicolas Fedor & FIFA, award of 9 May 2016. From this award it

follows that FIFA applied the incorrect version of the RSTP in its decision of

22 June 2015 as a result of which Art. 12bis was not applicable.

[13]

PSC 30 November 2015, no. 10151052.

[14] Also

in its award of 17 June 2016, another Sole Arbitrator stressed that as Art.

12bis has been implemented within the 2015 edition of the RSTP, FIFA has the

power to impose a sanction listed in Art. 12bis(4) RSTP in that specific case. See

CAS 2015/A/4310 Al Hilal

Saudi Club v. Abdou Kader Mangane, award of 17 June 2016.

[15]

See inter alia DRC 7 September 2011,

no. 9111901 (two months) and DRC 11 May 2011, no. 129795 (three months). See

also DRC 17 December 2015, no. 12151368. Please note that CAS will hold on to a

period of three months in order to establish that a just cause exists; See inter alia CAS 2015/A/4158 Qingdao

Zhongneng Football Club v. Blaz Sliskovic, award of 28 April 2016.