Update: On 14 April footballleaks released a series of documents concerning Sporting de Gijón. Therefore, I have updated this blog on 19 April to take into account the new information provided.

Doyen Sports’ TPO (or TPI) model has been touted as a “viable alternative source of finance much needed by the large majority

of football clubs in Europe". These are the

words of Doyen’s CEO, Nélio Lucas, during a debate on (the prohibition of) TPO

held at the European Parliament in Brussels last January. During that same

debate, La Liga’s president, Javier

Tebas, contended that professional football clubs, as private undertakings,

should have the right to obtain funding by private investors to, among other

reasons, “pay off the club’s debts or to compete better”. Indeed, defendants

of the TPO model continuously argue that third party investors, such as Doyen, only

have the clubs’ best interests in mind, being the only ones capable and willing

to prevent professional football clubs from going bankrupt. This claim constitutes

an important argument for the defendants of the TPO model, such as La Liga and La Liga Portuguesa, who have jointly submitted a complaint in front of the

European Commission against FIFA’s ban of the practice.[1]

The eruption of footballleaks provided the essential material necessary to test this claim. It allows

us to better analyse and understand the functioning of third party investment and

the consequences for clubs who use these services. The leaked contracts between

Doyen and, for example, FC Twente, showed that the club’s short term financial

boost came at the expense of its long-term financial stability. If a club is

incapable of transferring players for at least the minimum price set in Doyen’s

contracts, it will find itself in a financially more precarious situation than

before signing the Economic Rights Participation Agreement (ERPA). TPO might

have made FC Twente more competitive in the short run, in the long run it

pushed the club (very) close to bankruptcy.

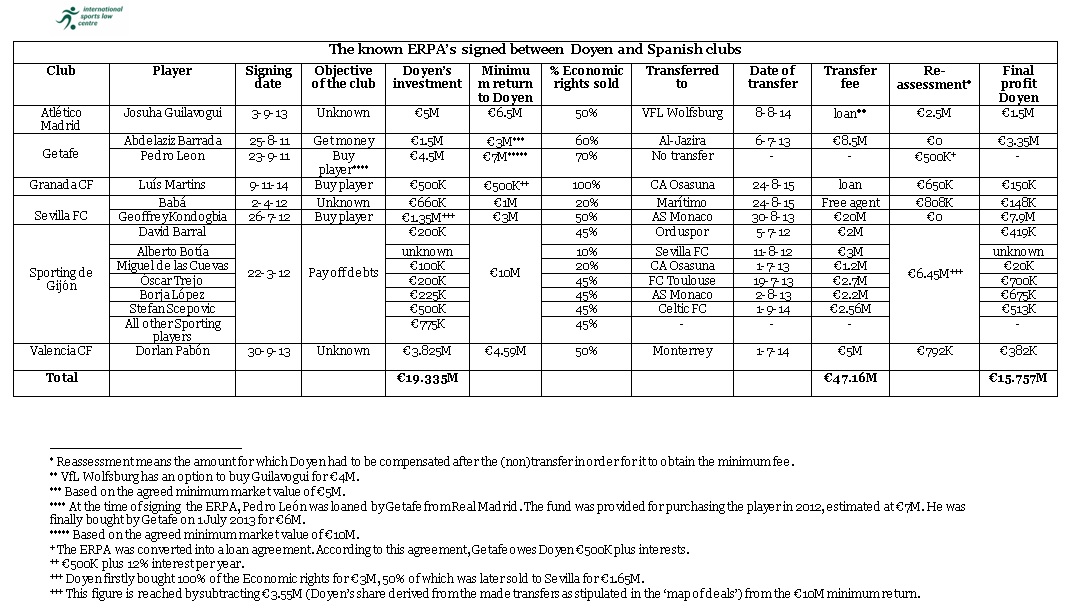

More than four months after its launch, footballleaks continues to publish documents from the football

world, most notably Doyen’s ERPAs involving Spanish clubs. For this blog, our

dataset will cover the two ERPAs between Doyen and Sporting de Gijón (found here and here); the ERPAs between Doyen and Sevilla FC for

Kondogbia and Babá; the ERPAs between Doyen and Getafe for Abdelazziz Barreda and Pedro León; the ERPA between Doyen and Granada CF for Luís Martins; the ERPA between Doyen and Atlético Madrid for Josuha Guilavogui; and the ERPA between Doyen and Valencia CF for Dorlan Pabón.

The first part of this blog will provide background information on the

recent economic history of Spanish football. The posterior in-depth analysis of

the ERPAs will thus be placed in context. The blog will also include a table

with the relevant facts from the ERPAs completed with the information included

in an Excel document showing a map of deals and transactions allegedly conducted by Doyen and recently published on footballleaks. Relevant facts and

figures that are not found in the ERPAs or in the Excel document, will be taken

from the website www.transfermarkt.de. Based on the

outcome of the analysis, we will attempt to conclude whether, and to what

extent, the ERPAs have been profitable for the clubs involved, from a financial

and competitive perspective.

Financial misery and TV

rights inequality off the field

The financial misery

Spain was one of the countries most affected by the global financial

crisis that commenced in 2008. The unemployment rate was above 25% for a long period of time and its budget deficit was

about 10% from 2008 to 2012. The (professional) football sector also suffered

from this general financial crisis. A study on the financial situation of Spanish clubs during the period 2007-2011 shows that by June 2011, 80% of La Liga clubs had a negative working

capital. This meant that the clubs’ short term assets were not enough to cover

the short term debts. The study further explains that the main reason for the

financial difficulties is the excess of expenditures on players, i.e. paying

transfer fees and salaries that clubs cannot afford. Not surprisingly, by 2011,

half of the clubs from the Spanish first and second division had entered bankruptcy proceedings. A large part of the total debt was owed to the Spanish public

authorities. In 2012, clubs in Spain's top two divisions collectively owed some

€750 million to the tax authorities and another €600 million to the social security system. One of the

teams who signed ERPAs with Doyen, Atlético Madrid, was known to have a tax

debt which accounted for a fifth of the entire league’s tax debt. In fact, their tax debt of over €120 million amounted to over 60% of

their annual revenue. Almost 40% of the clubs in the top two divisions

presented negative equity, meaning that they were in clear need for funds from

other parties. The general economic crisis prevented clubs to get these funds

through normal means, like shareholders, members, sponsorships and bank loans. Local

authorities were many times willing to aid their clubs. For example, the

municipality of Gijón had rescued Sporting de Gijón by relocating its youth training

facilities and subsequently buying the facilities for

€12 million. Another example is that of Valencia CF. In its ambition to

grow, the club decided to build a new stadium. The idea was to finance the new

stadium by selling the old stadium. Once again, due to the financial crisis,

and particularly the collapse of the housing market, it suddenly was incapable

of selling the old stadium for the required price. The construction on the new

stadium had already commenced with loaned money which could not be paid back. The

municipality’s decision to place a State guarantee on this loan has been the

subject of a formal State aid investigation by the European Commission.

TV Rights income inequality

One of the most important ways to generate income for professional

football clubs is through the selling of TV rights. The Spanish clubs combined generated

roughly €700 million per year from the selling of TV rights between 2010 and 2015.[2]

This is slightly more than the €628 million the German Bundesliga was making per year

between 2013 and 2016, but less than €940 million the Italian league was making in the

2012-13 season. The English Premier League is in a league of its own in this regard, which is making about €1.2

billion per year from the 2013-14 season onwards.[3]

Notwithstanding the total €700 million a year, most Spanish clubs do not

derive enough money from selling the TV rights to compensate their losses. One

has to keep in mind that where the clubs of Europe’s other major football

leagues (e.g. England, Germany, France and Italy) were selling their TV rights

jointly, Spanish clubs were still selling their TV rights individually. By

means of the individual selling system, Spain’s two most popular clubs, Real

Madrid and FC Barcelona, were capable of selling their TV rights for much more

money than the other clubs. In the 2010/11 season for example, out of

the €641 million generated in total, FC Barcelona got €163 million, whereas

Real Madrid got €156 million. The remaining 16 clubs of La Liga had to share the remaining €322 million, which is slightly

more than €20 million per club on average. By contrast, the ‘smaller clubs’ of

the English Premier League were still making at least €49 million in that same season,

which is two-and-a-half times as much as their Spanish counterparts.[4]

Even the club that was earning least money in Italy in 2012, Pescara, was

earning more per year from the selling of TV rights than the average Spanish

club (€25 million).

Calls for a fairer distribution of TV rights income in Spain have been

heard for years, particularly from the smaller clubs, but the switch to a joint selling system will only take place as of the start of the 2016-17 season. It is

believed that continuous lobbying by Real Madrid and FC Barcelona against the joint selling system is the main reason for this delay. In

a way, it could be argued that apart from reckless risks on the transfer market

and the effects of the Spanish financial crisis, the dominant position of Real

Madrid and FC Barcelona is what led to many Spanish clubs being in severe financial

difficulties. The urge of these clubs to turn to investment companies like

Doyen becomes more understandable, given that the system itself did not allow

them from obtaining funds from other ‘normal’ sources.

The ERPA’s and its

aftermaths explained

On the day of writing this blog (12 April 2016), nine ERPAs between

Doyen and Spanish football clubs were published on the website of footballleaks. The ERPAs are divided in

two groups: Firstly, the ERPAs that proved to be successful for both the club

and Doyen are analysed; the second part combines all the ERPAs in which the

players concerned were either not sold for high enough profit, or not transferred

at all. As will be shown, these ERPAs had mostly negative financial

consequences for the clubs.

The successful ERPAS:

Kondogbia and Barrada

Sevilla’s recent sporting successes, most notably

winning the Europa League four times since 2006, are said to have been the

result of a high level youth academy combined with an excellent scouting

network. However, it has never been a secret that Sevilla made use of the

services provided by Doyen, including the signing of ERPAs. In a well-publicised seminar on TPO that took place in April 2015, Sevilla defended the TPO model and made

clear that it was against an outright ban of the practice. The ERPA concerning Geoffrey Kondogbia and his subsequent transfer to AS Monaco can explain why Sevilla is in

favour of the TPO model. Kondogbia was transferred from RC Lens to Sevilla on

the same date as the signing of the ERPA (26 July 2012) for €3 million. With

the objective of obtaining 100% of the Economic rights, Doyen paid RC Lens the

full amount of the transfer fee. In turn, Sevilla would buy from Doyen 50% of

the economic rights for €1.65 million. Even though the minimum transfer fee was

set by the parties at €6 million, Kondogbia was sold only one year later to AS

Monaco for a staggering €20 million. An excellent deal for Doyen, which registered

a profit of €7.89 million.[5]

This ERPA is an example of a collaboration between a club and an investment

fund, which has been highly profitable for both. With the “help” of Doyen,

Sevilla managed to sign a young player and sell him for a profit not long

after. However, as can be seen below, even Sevilla has signed ERPAs that have

not been very beneficial for the club.

A second “successful ERPA” signed between Doyen and a Spanish club was the ERPA between Doyen and Getafe for Barrada. Similar to many other ERPAs, it stipulated that Getafe was not able to

obtain financial support from the banking system due “to the current financial

crisis”. Therefore, Getafe decided to sell 60% of the economic rights of one of

its most promising young players for €1.5 million to Doyen. Both parties agreed

that the minimum transfer value of Barrada was €5 million. Consequently, as can

be deducted under paragraph 7 of the ERPA, Doyen’s minimum return would always

be at least €3 million (60% of €5 million), guaranteeing Doyen a profit of €1.5

million (€3 million minimum return minus €1.5 million grant fee). The minimum

return was easily surpassed after Barrada was transferred to Al-Jazira for €8.5

million in 2013. In accordance with Doyen’s own figures, the investment fund

obtained €3.35 million for this transfer, a profit of 223%.[6]

The many “failed”

ERPAs

Atlético Madrid was no novice to the practice of TPO when it sold 50% of

Joshua Guivalogui’s economic rights for

€5 million to Doyen. As can be seen from the ‘Map of Deals’, Atlético had

previously sold 33% of the economic rights of the highly successful Atlético

player, Falcao, to Doyen for €10 million. His later transfer to AS Monaco for

€43 million was probably also economically beneficial for Atlético. Guivalogui,

however, has been less successful wearing an Atlético shirt. He has played

seven games in total for the club in two-and-a-half years, having been loaned

to St-Étienne for the 2013-14 season, and to VfL Wolfsburg for the 2014-15 and

2015-16 seasons. If Wolfsburg decides to lift the option it has to buy Guivalogui

for €4 million[7],

Atlético Madrid will probably need to pay an additional amount to Doyen in

order to reach the agreed minimum fee of €6.5 million.[8]

As regards Sevilla FC, where the ERPA concerning Kondogbia can be seen

as “successful”, Babá’s ERPA tells a completely

different story. Sevilla sold 20% of Babá’s economic rights for €660.000 to

Doyen in 2012. Nonetheless, Babá never managed to secure a spot in the Sevilla

squad and he was loaned out to Getafe and Levante between 2013 and 2015. After

his contract expired with Sevilla in the summer of 2015, he moved back to his

former club Marítimo as a free agent. Although Sevilla did not receive a fee

for this transfer, Doyen still obtained a guaranteed profit of €148.000, as can

be seen from the ‘map of deals’.

The Guivalogui ERPA and the Babá ERPA tell a similar story. Both players

did not fulfil the expectations the clubs had of them at the moment Doyen

bought parts of their economic rights. As a result, they were transferred, or

are going to be transferred, for an amount well below the agreed minimum

return. A similar run of events occurred with Luís Martins and Dorlan Pabon. Both players were

not successful at Granada and Valencia respectively, and were transferred at a

loss for the club. The exact figures of the transfers can be found in the table

below.

The ERPA’s signed between Doyen and Sporting de Gijón are particularly

interesting in terms of “failure”, because they illustrate perfectly the

desperate situation the club found itself in. Sporting has been on the verge of

disappearing not once, but several times in the last 10 to 15 years. In 2005,

its total debt amounted to €51 million, with more than half owed to the public authorities. As a result, the club entered bankruptcy proceedings. In 2007, a settlement was reached between

the club and its creditors. Even though the club still had a debt of €35.8

million, a Spanish court decided to terminate the bankruptcy proceedings. By

the second half of 2011, the club presented a positive balance

sheet at the shareholders’ general assembly for

a fifth year in a row, but in reality Sporting was still acute financial

difficulties, as the club would admit later on. It is this acute need

for money that made the club turned to Doyen twice in less than a year. The

fact that Sporting de Gijón is still alive today (albeit in danger of

relegating to the second division), makes one wonder whether the ERPA with

Doyen actually aided the club in its fight for survival or whether it worsened

the situation in a similar way as FC Twente’s.

The first agreement concerns the purchase

for €2 million of part of the economic rights of nine players who, at the time

of signing, were registered as Sporting players.[9]

Future transfers of one or more of these players would need to generate a

profit of €7 million for Doyen.[10]

The lifespan of the first agreement was not very long, as it was replaced by a second ERPA on 22 March 2012.

Indeed, Sporting de Gijón stated officially on 23 February 2016

that the first ERPA never deployed any legal effects.

The first ERPA and the second ERPA between Doyen and Sporting show some

clear similarities. For an amount of €2 million, Doyen buys 25% of the economic

rights of all the players of both the first team and Sporting B (the second

team).[11]

This percentage remains 25% until Doyen obtains an amount of €7 million

from the transfers of Sporting players to other clubs. Once this amount is

reached, the percentage will be reduced to 15% until a further €3 million is

earned by Doyen. Therefore, the minimum return Doyen should get is that of €10

million. Should Doyen not have received €7 million or more by 31 January 2015,

the percentage of the economic rights owned by Doyen of all the Sporting and

Sporting B players will be increased to 35%. Doyen's share of the economic rights would also increase to 35% if the club relegates from the first division (clause 2.5). A further important element of the ERPA is clause 4.1, by which Sporting names Doyen as the exclusive agent (intermediary) of the club for all transfer and loan operations of Sporting players.

By using the ‘map of deals’ and transfermarkt,

we have listed all Sporting and Sporting B players sold after March 2012.

These players were:

-

Davud Barral – sold

for €2 million to Orduspor on 5 July 2012;

-

Alberto Botía – sold

for €3 million to Sevilla FC on 11 August 2012;

-

Miguel de las Cuevas

– sold for €1.2 million to CA Osasuna on 1 July 2013;

-

Óscar Guido Trejo –

sold for €2.7 million to FC Toulouse on 19 July 2013;

-

Borja López - sold

for €2.2 million to AS Monaco on 2 August 2013;

-

Stefan Scepovic - sold

for €2.56 million to Celtic FC on 1 September 2014.

A closer look at the ‘map of deals’ shows one important discrepancy

compared to the ERPA of 22 March 2012. The share of economic rights owned by

Doyen were not 25% (as stipulated in the ERPA), but 45%.

Thanks to footballleaks' release of the so-called 'Escritura de Liquidación' on 14 April we now know what caused this increase. Firstly, in accordance with clause 2.5 of the ERPA, the economic rights owned by Doyen of all the Sporting players (except Botía and De las Cuevas) increased to 35%, since Sporting relegated to the second division in May 2012. Secondly, being an intermediary in all of these transfers, Doyen was entitled to an additional 10% of all the income generated from the transfers.[12] The ‘map of deals’ shows that the transfers of

Sporting players has so far led to Doyen receiving more than €3.5 million, a

profit of about €1.5 million for their €2 million investment. Nonetheless, this

figure is still well short of the minimum return Doyen expects to get of €10

million. In other words, should the ERPA still be in force, Sporting is still

required to sell more players if it is to meet its obligations towards Doyen.

Table summarizing the

analysed ERPA’s signed between Doyen and Spanish clubs

Conclusion

The reason that many Spanish clubs decided to sell economic rights of

players to companies like Doyen from about 2011 to 2015 (the year FIFA banned

the practice) is relatively straightforward: The financial crisis was heavily

felt in Spanish football, with many clubs incapable of paying off high debts

owed to the public authorities. Moreover, the difference between the financial

and competitive power of Real Madrid and FC Barcelona on the one hand, and all

the other clubs on the other was only getting bigger. Not only did competing at

national level become close to impossible, even smaller clubs from England were

generating more than twice the revenues of Spanish clubs. The chances of being

successful at European level were at risk.

Doyen was basically at the right place, at the right time. The ‘small’

Spanish clubs were in desperate need for money, either to compete or simply to

survive, and Doyen was willing to give them this money in return for (part of)

the economic rights of their football players. From the outside, it looks like

a perfect match between club and investment fund. However, was TPO profitable

for Spanish football clubs from a competitive and financial perspective?

From a financial perspective, the business is clearly lucrative for

Doyen. As can be seen in the table, by investing €19.335 million it so far made

a profit of €15.757 million.[13]

In other words, an 81.5% profit! The same cannot be said for the clubs. Only the

transfers of Barrada from Getafe to Al-Jazira and Kondogbia from Sevilla to AS

Monaco were profitable. For all the other ERPAs, it appears that an a posteriori compensation to Doyen was necessary,

because the amount obtained through the transfer could not cover the minimum

return secured to Doyen in the ERPAs.

The legal discussions on TPO to a large extent focused on whether the

practice leads to an unauthorized influence of third parties on the internal

governance and policies of a club; and on whether a complete ban is contrary to

(EU) competition law. Yet, the aspect that remains underexposed in the author’s

opinion is the severe negative financial effect TPO can have on a football

club. As we have discussed a couple of months ago in a blog on FC Twente, the financial

position of the Dutch club deteriorated after signing the ERPA to such an

extent that the club is now in serious danger of disappearing all together.

It is possible, though unlikely, that FC Twente’s downfall was an

exception. However, one should not

underestimate Sporting de Gijon’s current financial situation, for example. A

closer look at the ‘map of deals’ tells us that in March 2015 Sporting had only

paid €250.000 of the €3.5 million it owed Doyen. A total debt of at least €3

million was confirmed in an official joined statement, dated 29 February 2016. The statement further holds that this debt has

to be repaid before 2019, but one cannot help thinking that, for a club like

Sporting de Gijón, this is easier said than done. Getting the money from future

transfers should be complicated if Sporting only partially owns the economic

rights of its own players, plus a looming relegation to the second division at

the end of this season will not be beneficial either.[14]

[1] More information on the TPO ban can be

found in our previous Blogs, such as “Blog

Symposium: FIFA’s TPO ban and its compatibility with EU competition law –

Introduction”.

[2] The total amount

generated for the 2010/11 season was €641, see Mail Online, “Barca and Real consider sharing TV rights to make La

Liga more competitive”; The total amount generated for the 2014/15 season

was €742.5 million, see Marca, “Así

será el reparto del dinero televisivo”.

[3] As of the 2016-17

season, The English Premier League will make €2.1 billion per year, see Mail Online, "Premier League set for £3bn windfall from global TV rights as rival broadcasters slug it out to screen England-based superstars"

[4] More information on

the selling of TV rights in football can be found in our previous Blogs, such as “Why the European Commission will not

star in the Spanish TV rights Telenovela”.

[5] See: Map of deals and transactions updated until 10 March 2015.

[6] See: Map of deals

and transactions updated until 10 March 2015.

[7] Transfermarkt

- Josuha Guilavogui.

[8] The original minimum

return of €5.5 million set in September 2013 was increased every year by

€500.000 until 1 September 2015, since Doyen continued to own 50% of the

Guilavogui’s economic rights.

[9] The players

concerned were Roberto Canella Suárez, Álvaro Bustos Sandoval, Alejandro

Serrano García, Abdou Karim Tima, Mendy Formose, Juan Muñiz Gallego, Sergio

Álvarez Díaz, Óscar Guido Trejo and David Barral Torres.

[10] In the first phase,

Doyen receives a percentage of 50% of the economic rights of the nine players

until Doyen received an amount of €5 million for the transfer of one or more of

those players. After Doyen receives its first €5 million, Doyen’s ownership of

the economic rights of the remaining players is to be reduced to 40% until

Doyen received an additional €1 million. Once Doyen receives this additional €1

million, Doyen’s ownership of the economic rights of the remaining players

would be reduced to 30% until Doyen again receives €1 million from the selling

of those players. Consequently, the agreement stipulates that Doyen is to

receive an amount equal or superior to €7 million for the transfer of players

in which it partly owned the economic rights.

[11] As an exception,

Doyen only gets 10% of the economic rights of the players Alberto Botía and

Miguel de las Cuevas.

[12] Moreover, the 20% of the transfer fee for De las Cuevas that Sporting owed Doyen consisted of 10% for the

economic rights and 10% as an agency fee.

[13] This figure might

even get higher when taking into account that Doyen had a share in all Sporting

de Gijón players and the fact that Pedro León is still registered as a Getafe

player.

[14] With seven matches

to go, Sporting finds itself in 17th place.