Editor’s Note: Saverio

Spera is an Italian lawyer and LL.M. graduate in International Business Law from

King’s College London. He is currently an intern at the ASSER International

Sports Law Centre.

The time

is ripe to take a closer look at the CAS and its transparency, as this is one

of the ways to ensure its public accountability and its legitimacy. From 1986

to 2013, the number of arbitrations submitted to the CAS has grown from 2 to more

than 400 a year. More specifically, the number of appeals submitted almost doubled

in less than ten years (from 175 in 2006, to 349 in 2013[1]).

Therefore, the Court can be considered the judicial apex of an emerging transnational

sports law (or lex sportiva).[2]

In turn, the increased authority and power of this institution calls for

increased transparency, in order to ensure its legitimacy.[3]

One might

ask why focusing on the level of transparency of an arbitral institution is so

important, given the traditional aura of confidentiality that has always

accompanied arbitral proceedings. The answer is multifaceted. Firstly, a cursory

look at the developments of international commercial arbitration and, more

significantly, international investment arbitration shows that confidentiality

is not anymore the untouchable hallmark that it once was.[4]

Secondly, and most importantly, the peculiarities of the CAS Appeal Procedure

make this body look like an arbitral institution but function in a way that is

more akin to an international court. Furthermore, it is well known that one of

the foundations of domestic and international arbitration is party autonomy.

Parties freely opt to defer their dispute to an arbitral panel rather than a

court for a variety of reasons, one of which can actually be the confidential

nature of arbitration. That said, it is hard to ground the CAS Appeal Procedure on party autonomy. According to the CAS Code (Art. R47), in order for

the CAS to have the necessary jurisdiction to hear an appeal, either the

parties have expressly agreed to it, or an arbitration clause is contained in

the statutes or regulations of the governing body issuing the decision under

appeal. In practice, the regulations of the Sports-Governing Body often contain

an arbitration clause in favour of the CAS, or these bodies require athletes to

sign a specific arbitration agreement as a precondition for participating in an

event or competition.[5]

An example of the former practice is given by the FIFA

Statutes, which – at Art. 59 expressly require that national federations

insert an arbitration clause in favour of the CAS in their regulations, and –

at Art. 58 imposes that “(a)ppeals

against final decisions passed by FIFA’s legal bodies and against decisions

passed by confederations, members associations or leagues shall be lodged with

CAS”. An example of the latter is given by Bye-law 6 to Rule 44 of the

Olympic Charter, which obliges athletes entering the Olympic Games to sign

a form containing a clause which devolves the CAS exclusive jurisdiction over

any dispute arising in connection with the participation to the Games.

In such a

framework, athletes face the alternative between not competing at all and accepting to resort to the CAS in case of a dispute. The post-consensual

foundation of the system is a feature that stands in irreconcilable conflict

with the logic of international commercial arbitration, based on party

autonomy. If the free will of the parties in choosing to arbitrate rather than

litigate justifies, to a limited extent, a limitation of transparency in favour

of confidentiality in international commercial arbitration, what justifies a

low level of transparency at the CAS?

In this

regard, for example, the level of transparency of international investment arbitration

has been subjected to intense scrutiny. Transparency should then, a fortiori, be scrutinized in the realm

of sports arbitration, and in particular at the CAS, whose central position in

the lex sportiva is widely

acknowledged.

This blog

will focus on the two key issues related to the CAS’ transparency. Firstly, the

availability of information about arbitrators on the CAS website. Secondly, and

most importantly, the publication and ready availability of CAS awards. Furthermore,

as the CAS ordinary procedure resembles traditional commercial arbitration, the

blog will be only concerned with awards stemming from the Appeal procedure.

Lack of

transparency concerning the arbitrators

Articles

R33 to R36 of the CAS Code deal with independence and impartiality of CAS

Arbitrators as a conditio sine qua non

of the arbitration proceedings.[6]

Moreover, these provisions provide for mechanisms to guarantee this independence

together with measures at disposal of the parties that want to challenge the independence or impartiality of an arbitrator. Yet

to diligently exercise their right, and ensure the independence of arbitrators,

parties need full access to information on the arbitrators.

Analysed

through the lens of transparency, the problems arise from the fact that it is

difficult to assess the inclinations and history of arbitrators prior to

initiating proceedings before the CAS. In other words, given the limited information

on arbitrators found on the CAS website[7],

parties are not equipped with the necessary tools to make a fully informed

choice. There is always a risk for conflicts of interest that parties to CAS arbitration

should be able to assess on a level playing field, i.e. through a simple visit

to the CAS website. Thus, more transparency with regards to the information

provided about arbitrators would help reduce the prevailing information

asymmetry between the one-shotters (mainly the athletes and their lawyers) and

the repeat players (mainly the SGBs and their lawyers/legal counsels) at the

CAS. Not only should the section ‘List of Arbitrators’ give access to each

arbitrator’s jurisprudential record and relevant past or present contractual

relationships. It should also list publications or comments arbitrators have

released in the past, as some of them might have already formed a view on a

certain type of cases. Although this is not always an indicator of bias, it would

permit the parties to make a better-informed choice. Furthermore, and more

importantly, in order to level the playing field between the parties, the

information about arbitrators should also include a reference to who nominated

them in past CAS arbitrations. Additionally, the fact that dissenting opinions

are not recognised nor notified by CAS[8] adds

another layer to a feeling of opacity surrounding the arbitrators’ profiles and

views.

Finally,

according to Art. R33 CAS Code, ICAS draws up the list of arbitrators. From the

point of view of securing the CAS’ transparency and accountability, it would be

necessary that the nomination process be publicly scrutinized. Thus, ICAS

should publish the name of the institutions putting forward each new

arbitrator, as well as the reasons why they were considered adequate

candidates.

Lack of

transparency in the publication of awards

The lack

of transparency of the CAS is further illustrated by the process followed for the

publication of its awards (and in particular awards of the Appeal Division).

The CAS

Code provides rules for the publication of awards in the Ordinary Procedure

(Art. R43) and the Appeal Procedure (Art. R59). For the Ordinary Procedure the

default rule is confidentiality ‘unless all parties agree or the Division

President so decides’. The rule favours a presumption of confidentiality because

the CAS Ordinary Procedure is mainly used for commercial disputes based on the

clear consensual agreement of the parties to submit to CAS arbitration. However,

it is interesting to note that even in the similar realm of international

commercial arbitration confidentiality is not an unchallenged hallmark anymore.

International commercial arbitration awards are being voluntarily published

with increased frequency[9]

and some authors even advocate the adoption of a presumption of openness of the

awards.[10]

In fact, although the need for transparency in commercial arbitration is less

compelling than in investment arbitration due to the private interests at

stake, the general public may still be affected in a variety of ways and

therefore needs to have access to the decisions. [11]

Conversely,

the default rule for the CAS Appeal Procedure is publicity. Art. R 59(7) provides

that “(t)he award, a summary and/or a

press release setting forth the results of the proceedings shall be made public

by CAS, unless both parties agree that they should remain confidential. In any

event, the other elements of the case record shall remain confidential”. The

rationale for a different treatment between the Ordinary Procedure and the

Appeal Procedure lies in the consideration that, unlike the more commercially-oriented

disputes destined to the Ordinary Procedure, appeals concern disciplinary decisions

issued by international federations that are of interest to the public and

that, in any case, might have already been disclosed.[12]

From a

comparative point of view, it is noteworthy that the public interests at stake

are one of the reasons why international investment arbitration, as opposed to

– or at least more rapidly than – commercial arbitration, has shifted from a

presumption of confidentiality to a presumption of openness.[13]

In oversimplified terms, investment arbitration disputes involve States, which

– for instance – have to resort to the national budget to pay in case of adverse

awards. Also, governments’ public policies are often challenged before

investment arbitral tribunals by foreign investors. All these matters are of

evident public interest and were a key factor in pushing for more transparency.

In the field of international investment law this process was initially

triggered by NAFTA

Chapter 11 and its interpretation

by the Free Trade Commission (FTC), followed by the 2006

amendment to the ICSID Arbitration Rules. The development of the UNCITRAL

Rules on Transparency, which also provide for amicus curiae submissions and open hearings, made another important

stride in that direction.

Turning

the attention back to the CAS, all the awards published are released on the CAS website. Although

it could be argued that, at least for the Appeal Procedure, the default rule

should go further down the road of transparency following the trend in treaty

investment arbitration, a transparency-weary commentator could potentially be

satisfied with the existing framework of the CAS Code, if only the CAS would

implement it consistently. Instead, the CAS administration seems to follow a

rather opaque and discretionary publication policy that gives rise to major

transparency issues, the main one being the fact that, as we will see, only a

limited number of awards are published on the CAS website.

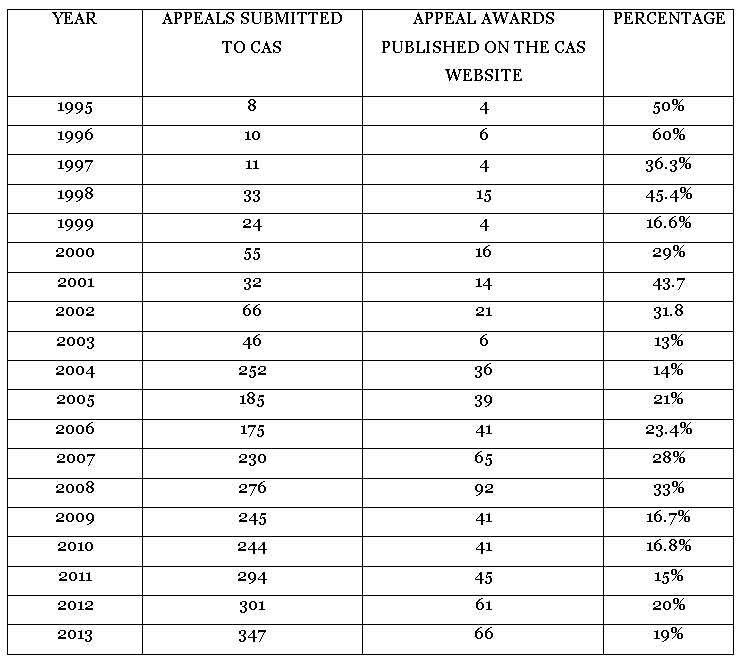

The CAS

statistics include the number of Appeals submitted to the CAS (until 2013) and it is easy to determine the number of awards published per year in the CAS Database

between the entry into force of the Code (22 November 1994) and the end of 2013.

We compared the two figures and obtained the percentage of awards

published each year in relation to the number of appeals submitted.[14]

A quick

glimpse at the table suffices to notice an unfortunate trend in the publication

policy of the CAS. If we exclude the first couple of years, in which the number

of appeals submitted were extremely limited, the percentage of awards published

is constantly below 30% (with the sole exceptions of 2001, 2002 and 2008, and –

in any case –substantially below the still hardly acceptable threshold of 50%).

The figures get even more striking as the workload of the CAS increased. From

2009 onwards, the average percentage of appeal awards published stands at a disappointing

17.5%!

This

state of affairs significantly hampers predictability and coherence of the CAS

jurisprudence, as well as threatens the objective of providing legal certainty

to the sporting world at large, which is at the heart of the appeal procedure

at the CAS. Indeed, the CAS jurisprudence has acquired throughout the years a

law-making role that, in turn, calls for full transparency of its awards. If we

read through the CAS case law we can find that arbitrators often refer, and

demonstrate a consistent deference, to CAS jurisprudence.[15]

To this end, transparency becomes a central issue, as it prevents inconsistency

by subjecting the CAS panels to the critical scrutiny of their peers. After

all, the need for coherence has been stressed by the CAS itself when it has

recognised that, in spite of the lack of stare

decisis at the CAS, arbitrators are disposed to “follow the reasoning of a

previous Tribunal […] both of a sense of comity and because of the desirability

of consistent decision of the CAS, unless there were a compelling reason, in

the interest of justice, not to do so”.[16]

From the point of view of the potential parties to CAS arbitration this is of

particular importance. If awards are systematically published, lawyers (and in fine the parties) are better able to

determine before initiating the arbitration whether their case is likely to

succeed. Furthermore, the availability of awards on the CAS website would put

repeat players and one-shotters on an equal playing field, eliminating – at

least in this regard – the edge that the former gain on the latter.

The need

for predictability requires not only awards to be published, but also to be

promptly published after they are rendered. The potential disputing parties

might have an interest in having previous awards available quickly. In this

regard the above-mentioned role of precedents in CAS jurisprudence plays again

a significant role. It has been noticed how some decisions are based on

solutions adopted in previous awards that have not yet been published.[17]

Having the award readily at disposal is necessary for the parties’ legal

argumentation. This way the party’s counsel can, respectively, either use the

award as a valid leg to bolster her arguments or criticise the position

recently adopted by a panel on the same issue.[18]

Additionally, a more systematic publication of recent awards online would

significantly contribute to increase the level of transparency at the CAS, as

the web represents a great opportunity for the public in terms of speed and

accessibility. On the CAS website it is possible to find a section specifically

dedicated to ‘recent decisions’. This section, though, does not seem to be

organised as systematically as it could be. The CAS’ policy regarding the

recent decision section of its website is extremely confusing. It includes some

awards from 2016 and 2015, but not all the awards from these years available in

the CAS database, as well as older awards from 2012 and 2011, which can hardly

count as ‘recent decisions’. Apart from the consideration that “these awards

disappear from the website after a few weeks and it is not possible to find

them anymore”[19], a more

systematic publication of the recent awards would be desirable. A valid model

to follow has been identified in the websites of the Italian Camera di

conciliazione e di arbitrato per lo sport (CCAS) and the Canadian Centre for

Ethics in Sports (CCES), where the decisions taken are systematically published

without excessive delay.[20]

Conclusion

There is

a clear, widespread and apparently unstoppable demand for transparency in

contemporary international law. This demand has been voiced by civil-society,

governments and international institutions with increased frequency. Thus, more

room for transparency has been made within international institutions in the

last few years.[21]

We have seen very briefly how even in the confidentiality-savvy field of

international arbitration transparency has made its way up on the ladder of

priorities. In sports arbitration, where the jurisdiction is often not

exercised over the parties on the basis of their consent[22],

the judicial activity of the CAS must be a

fortiori open to scrutiny not only by the parties but by the public at

large. There are many ways to evaluate the legitimacy of a court. One of these

is the persuasion among the public that an international court has the right to

exercise authority in a given domain. To be persuaded, it is essential that the

public has a possibility to assess how the CAS carries out its activities and,

therefore, be allowed the broadest access possible to CAS awards to be able to evaluate

(and criticize) their rationality. A greater transparency at the CAS would

allow for greater participation of those that might be affected by its

activity.

This call

for greater accountability of international courts and tribunals, though, does

not seem to resonate much at the CAS. If one looks, as we have done in this

blog, at the reality of transparency at the CAS, one cannot help feeling disappointed.

Information about arbitrators is scarce and it is hard to find any consistency

in the publication of CAS awards.

Yet the

CAS could intervene on these two key aspects. To this end, we propose a few

brief recommendations for the CAS administration to follow.

Firstly,

the section of the CAS website ‘List of Arbitrators’ should be enriched with

all the relevant information concerning arbitrators. Therefore:

First

recommendation: The CAS should include in the ‘List of

Arbitrators’ section of the website a downloadable individualized PDF

comprising: jurisprudential records, past or present relevant contractual

relationships, publications or comments arbitrators have released in the past

and a summary indicating who nominated them in past CAS arbitrations.

Secondly,

the CAS should make sure that all its appeal awards are promptly available to

the public. Therefore:

Second

recommendation: The CAS should simply remove the phrase ‘unless

both parties agree’ from the provision of Art. R59. Thereafter, parties would

be in principle deprived of the authority to veto the publication of a

sentence.

Even if

one believes that – notwithstanding its peculiarities – the Court operates as a

traditional arbitral institution, a systematic reform of the publication policy

of the CAS would be urgently needed. The CAS website (and database) need to be

modernized to facilitate a swift and easy access of the public to the awards.

Therefore:

Third

recommendation: The ‘recent decisions’ section should contain

(for a short timeframe, maximum three months) all the recently decided awards

and the database should provide all the awards rendered and not only less than

a fifth as is currently the case.

There is

much to do, but with a bit of will the CAS can become a world-wide leader in

terms of arbitral transparency and greatly strengthen its legitimacy and

standing in the eyes of its users and of the public at large.

[1] The statistics used for

this article are taken from the CAS

website, the available data stops on 31 December 2013.

[2] Lorenzo Casini, The Making of a Lex Sportiva by The Court of

Arbitration for Sport (2012). German

Law Journal, Vol. 12 n. 5, 452, Antoine Duval, Lex Sportiva: A playground for transnational

law (2013). European Law Journal, Vol. 19 Issue 6, 822-842.

[3] Anne Peters, Towards Transparency as a Global Norm in

Andrea Bianchi and Anne Peters, Transparency in International Law, Cambridge

University Press 2013, 557.

[4] See Cindy G. Buys, The tensions between confidentiality and

transparency in international arbitration, The American Review of

International Arbitration (2003), Catherine A. Rogers, Transparency in International Commercial

Arbitration (2006) and Stephan

W. Schill, Five times transparency in international investment law (2014), The Journal of World Investment and Trade, Volume 15, Issue 3-4.

[5] Rigozzi/Hassler, Sports Arbitration under the CAS Rules,

Chapter 5 in Arbitration in Switzerland, Kluwer Law International (2013), 988.

[6] Despina Mavromati &

Matthieu Reeb, The Code of the Court of

Arbitration for Sport, Commentary, Cases and Materials, Kluwer Law

International (2015), 134.

[7] In some cases information is

limited to a couple of lines, e.g. “Juris doctor; Professor of International

Law at […] University School of Law; practicing lawyer; international

arbitrator”. See http://www.tas-cas.org/en/arbitration/list-of-arbitrators-general-list.html,

accessed 19 January 2017.

[8] The last part of Art. R

59(2), inserted with the 2010 revision of the CAS Code, reads as follows: “Dissenting opinions are not recognized by

CAS and are not notified”.

[9] Catherine A. Rogers, Transparency

in International Commercial Arbitration, (2006). Penn State Law, 23.

[10] See, among others, Cindy

G. Buys, The tensions

between confidentiality and transparency in international arbitration,

The American Review of International Arbitration (2003), 121.

[11] Cindy G. Buys, Ibid,

135.

[12] Despina Mavromati &

Matthieu Reeb, The Code of the Court of

Arbitration for Sport, Commentary, Cases and Materials, Kluwer Law

International (2015), 588.

[13] Stephan W. Schill, Five

times transparency in international investment law (2014), The Journal

of World Investment and Trade, Volume 15, Issue 3-4, 369.

[14] The

accuracy of the findings is limited by the lack of precision of the CAS’

statistics. Namely, in the statistics section of the website it is possible to

retrieve only data referring to the Appeals submitted every year but not to the

appeal awards rendered. Therefore, our yearly comparison cannot take fully into

account the temporal shift between the submission of the case and the rendering

of the decision (as well as the limited number of cases which were withdrawn).

In other words, in reality, the share of awards published is probably slightly

higher than indicated in the table.

[15] Gabrielle Kaufmann-Kohler,

Arbitral

Precedent: Dream, Necessity or Excuse? (2006). Arbitration International, 365.

[16] CAS

96/149, A. C[ullwick] v. FINA, p. 251, 258 – 259, cited in Antonio Rigozzi,

l’Arbitrage internationale en matiére de

sport, (2005), 638.

[17] Antonio Rigozzi, l’Arbitrage

internationale en matiére de sport, (2005), 640.

[18] Going back with the memory

to a few years ago, it has be noted how Pavle Jovanovic’s counsel would have

had great benefit in having the possibility to read the award rendered in the

case that saw the French judoka Djamel Bouras opposing the International Judo

Federation in a doping case, which was not yet published when the Jovanovic case

was submitted. Had the award been promptly published he would have had the

chance to invoke the solution contained therein (See Antonio Rigozzi, l’Arbitrage internationale en matiére de

sport, (2005), 639).

[19] Antonio Rigozzi, ibid, 641.

[20] Antonio Rigozzi, ibid, 642.

[21] Anne

Peters, The

Transparency Turn of International Law (2015), The Chinese Journal of

Global Governance, 3.

[22] For a wider discussion on

the lack of consent in sports arbitration, see A. Rigozzi & F.

Robert-Tissot, “Consent”

in Sports Arbitration: Its Multiple Aspects’, in E. Geisinger & E. Trabaldo de Mestral (eds.), Sports

Arbitration: A Coach for other players? (2015),

59 -60; A.

M. Steingruber, Sports Arbitration: how

the structure and other features of competitive sports affect consent as it

relates to waiving judicial control, 20 American Review of International

Arbitration (2009), 59, 73; M.A. Weston, Doping Control, Mandatory Arbitration, and

Process Dangers for Accused Athletes in International Sports, 10

Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal

(2009), 5, 8; and D. H. Yi, Turning Medals into Metal: Evaluating the

Court of Arbitration of sport as an international tribunal, 6 Asper

Review of International Business and Trade Law (2006), 289, 312.