The last years has seen the European Commission being put under

increasing pressure to enforce EU State aid law in sport. For example, numerous

Parliamentary questions have been asked by Members of the European Parliament[1] regarding

alleged State aid to sporting clubs. In

reply to this pressure, on 21 March 2012, the European Commission, together

with UEFA, issued a statement. In this statement, the Commission held that the

objectives of the UEFA’s Financial Fair Play (FFP) Regulations are consistent

with the aims and objectives of European Union policy in the field of State aid.

Moreover, the Commission highlighted that it is willing to cooperate with UEFA when

enforcing the rules on EU State aid onto professional football. According to

the Commission, when football clubs experience financial difficulties, there is

a particular risk that public authorities may be tempted to grant State aid. Thus,

enforcing EU rules on State aid will ensure prudent economic management by

football clubs that will serve to protect both the interests of individual

clubs and players as well as the football sector in Europe as a whole.

Now that UEFA is in the process of enforcing its

FFP regulations on football clubs, the question remains whether the European Commission has kept its word

about its part of “the deal”. In other words, is there a visible change

regarding the enforcement of the EU State aid rules by the European Commission?

Article 107 of the treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

(TFEU) foresees that a Member State may not aid or subsidize private parties in distortion of free competition.

The State aid rules constitute one of the four policy areas forming EU

competition law. The others being the rules on cartels, abuse of dominance and

mergers. The European Court of Justice established long ago that EU competition

Law was also applicable to sporting entities[2],

but very little has ever been done or said about State aid in sport. In fact,

one could easily get the impression that the Commission deliberately avoided to

get its hands dirty with such problems. One famous example concerns a terrain qualification

change in Madrid in the late 90’s that proved hugely advantageous for Spanish

football club Real Madrid[3].

In this case, the Commission, even though agreeing that an advantage was

conferred to the club, simply stated that the new qualification of the terrain in

question does not appear to involve any transfer of resources by the State and could

therefore not be regarded as State aid within the meaning of article 107 TFEU.

So has anything changed since then, or more specifically, since 21 March

2012? The Commission has never been famous for its celerity, meaning that it

could take another few years before true change can be witnessed. The continuous

delays in coming to decisions has also been one of the main points of criticism by the European Ombudsman on the way the Commission is dealing with

State aid in sport. However, on a close look, one can distinguish the beginning

of a shift towards active enforcement of EU State aid law in sports.

On the day of the joint statement, the Commission published a decision indicating that it would initiate a formal

investigation into alleged State aid granted by Sweden for the construction of

a sporting arena for ice hockey and other indoor sports in the town of Uppsala.

The Swedish State notified the Commission that it had planned to grant EUR 16.5

million directly plus EUR 1.7 million for 25 years for the construction because

the arena would fulfil an objective of common interest. Moreover, due to its

multifunctional character, the arena would also be used for other sports and

events, such as concerts. Nonetheless, the Commission had doubts as regards the

necessity to use public funding for this projects and the reasons advanced by Sweden

to justify the need of a completely new arena instead of renovating an old one.

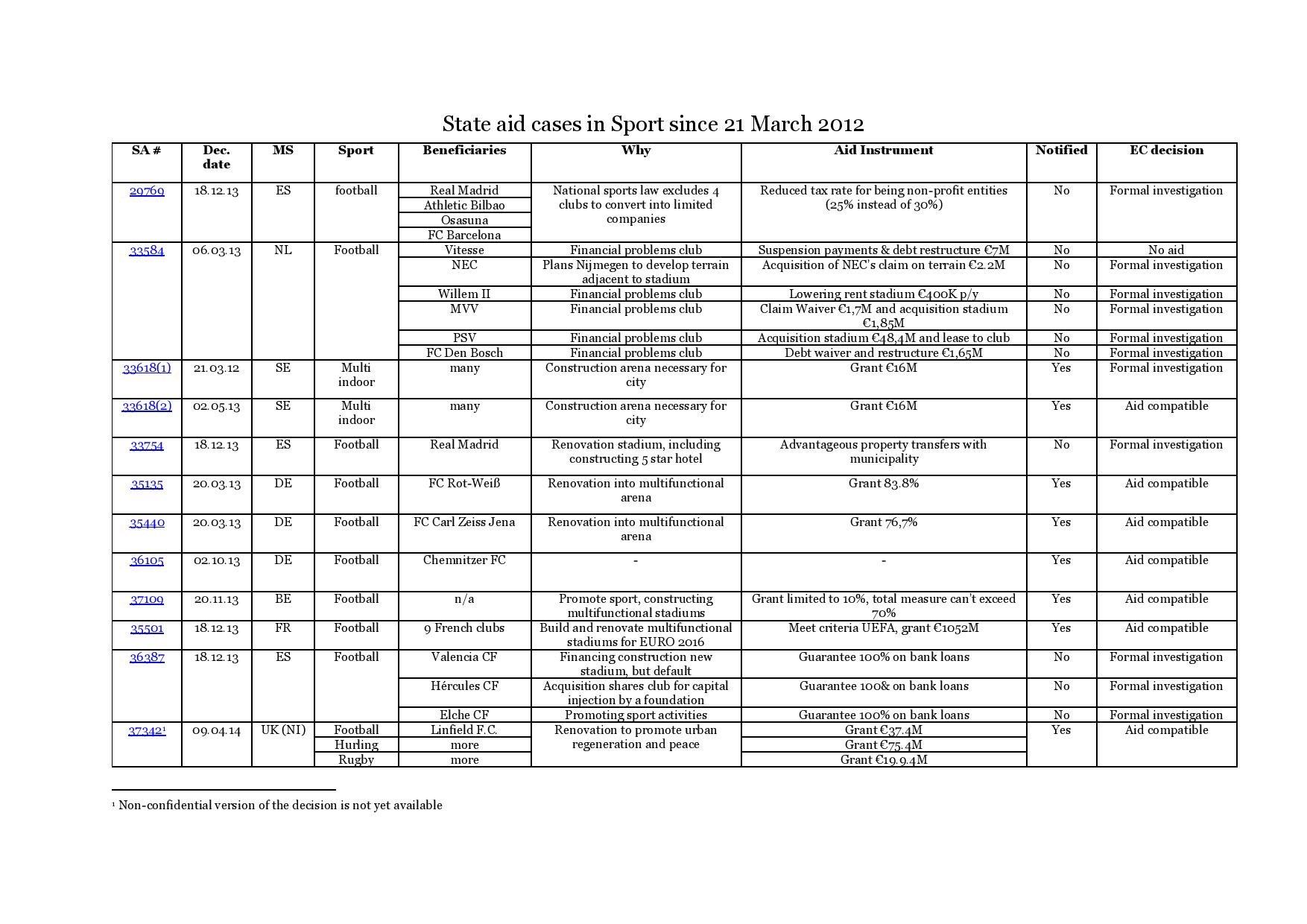

The Commission’s scrutiny of State aid in the field of sport did not end

there. Since March 2012 the Commission has dealt with 12 cases in which it had

to decide whether to launch an official investigation or not. The cases

included possible State aid to over 30 beneficiaries in six different Member

States, the latest one published 9 April of this year (see table). The aid measures

varied from grants for renovating old stadiums or constructing new ones, debt

waivers and reduced tax-rates for certain clubs, to acquisition of a stadium by

the municipality, guarantees on bank loans by the club and suspected

advantageous property transfers between a club and the municipality. In five

out of the 12 cases, the Commission has decided to launch an official

investigation in accordance with article 108(2) TFEU.

TableStateAidInSport.pdf (95.1KB)

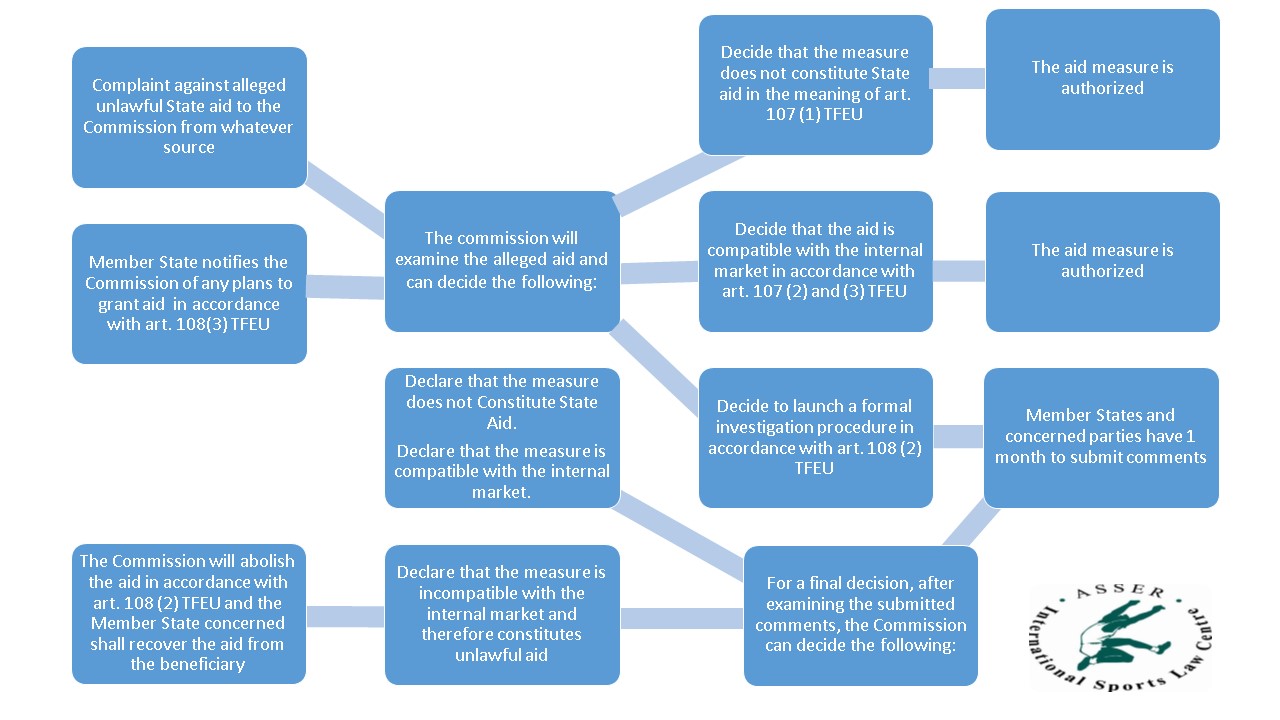

Launching an official investigation does not mean that the Member State in

question will get sanctioned for granting unauthorized State aid. Article

108(2) TFEU allows the Member States and concerned parties, such as the

beneficiaries, to submit comments and to respond to any doubts the Commission

might have regarding the legality of the aid. Indeed, on 2 May 2013, in its

final decision regarding the construction of a sporting arena in the town of

Uppsala, the Commission concluded that the granted aid is compatible with the

internal market in accordance with article 107(3)(c) TFEU[4]

and is therefore authorized. Nonetheless, four cases, which will be analyzed in

future blog posts, are still pending a final decision by the Commission. For

now, it is fair to say that the Commission has shifted towards an active

enforcement of EU State aid law in sports. However, whether the Commission is

prepared to “show its teeth” and sanction the Member States who granted

unlawful aid to sporting clubs remains unclear.

[1] See for example: E-005417/2011, E-004360/2011 and P-4699/09

[2] Case 36/74 Walrave

and Koch, (1974)

[3] The qualification change allowed Real Madrid to

sell its old training grounds. Though the exact price for the grounds remains

unknown, Real Madrid was suddenly capable of buying players like Figo and

Zidane for record fees.

[4] Article 107(3)(c) TFEU: “The following shall be compatible with the internal

market: aid to facilitate the development of certain economic activities or of

certain economic areas, where such aid does not adversely affect trading

conditions to an extent contrary to the common interest”.