Shortly after his election as IOC President, Thomas Bach announced his intention to initiate an introspective reflection and reform cycle dubbed (probably a reference to former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder’s publicly praised Agenda 2010) the Olympic Agenda 2020. The showdown of a year of intense brainstorming is to take place in the beginning of December 2014 during an IOC extraordinary session, in which fundamental reforms are expected.

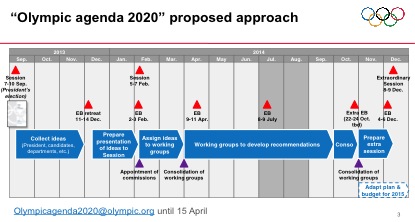

Graph 1: The Olympic Agenda’s Timeline

The aims of the Olympic Agenda: Cheaper, Simpler, “Hotter”

The

Olympic Agenda 2020 is aimed at securing the short- and long-term

success of the Olympic Games. To this end, six main themes, linked to

five “clusters of ideas”, were outlined in the IOC’s internal preparatory document:

the bidding procedure, the sustainability of the games, the uniqueness

(differentiation) of the Games, the Olympic programme, the Olympic Games

management and the Olympic Games audience.

The bidding procedure is currently very much under the spotlights, due to the serial withdrawal

of cities from their candidacy for the 2022 Winter Olympics. The

Olympic Agenda 2020 is first and foremost an exercise designed to

respond to this désamour; a process aimed at enhancing the

attractiveness of the Games to organizers as well as consumers.

Therefore, the IOC foresees an in depth reform of the bidding, making it

cheaper and easier for an interested city to candidate.

Moreover, the

IOC advocates sustainable Games. By sustainability it means prioritizing the economic viability of the Games. Only in a subsidiary

fashion does it entail a concern for their social impact and

environmental footprint. Such sustainable Games would be a radical

change compared to the latest Sochi Games, which were both very expensive and very environmentally destructive.

On paper, this is a noble objective to pursue, but the lack of concrete

proposals advanced so far does not bode well for its implementation.

Finally,

the IOC is very much concerned with the “hotness” of the Games or, in

other words, their attractiveness to consumers and athletes. Thus, it

suggests a number of changes to the Olympic Programme, to the

relationship of the IOC with other Sports Governing Bodies, to the

management structure in the organization of the Olympic Games and to the

way it targets its audience (opening up to new markets geographically

and technically). As one can see, the IOC had a specific plan in mind

when launching the Olympic Agenda 2020 and it focuses very much on the

“hotness” of the Games and its economical “sustainability” rather than

on its societal responsibility.

A global consultation: For what?

The Olympic Agenda 2020 boasts its responsiveness and openness to the public, embodied in a broad public consultation

concluded on 15 April 2014. Thus, the goals and themes suggested by the

IOC were, in theory at least, to be complemented and enriched by the

opinions raised by participants to the public consultation. Sadly, the

contributions to the consultation have not been made publicly available,

yet. Only the contributions published on-line by their authors are

freely accessible to public scrutiny, this is a regrettable lack of

transparency undermining the essence of such a participative endeavour.

From

the contributions publicly available one can draw a picture of the

demands posed to the IOC in the framework of the consultation and the

expectations of the public in this regard. Human Rights Watch, Swedwatch, the Norwegian Olympic Committee, the Swedish Trade Union, and the Gay Games Federation

have all submitted substantial contributions advocating an enhanced

protection of fundamental rights during the Olympics. To this end, they

suggest for example to impose minimum labour standards at the Olympic

building sites, fundamental rights criteria for selecting the host city

and an environmentally sustainable management of the Olympic Games. But, is

someone listening?

Working Groups: Behind closed doors

Last week, the IOC released

the composition of its 14 Working Groups (WGs), tasked with the formulation of theme-specific recommendations. Hence, these WGs will play a

decisive role in the substantial outcome of the whole process. Indeed,

the detailed recommendations provided will later be compiled and

submitted to the IOC session, the body responsible for amending the

Olympic Charter and deciding on the IOC’s fundamental political

orientations. The WGs include

IOC members and external experts. The themes attached to the WG are: Bidding Procedure (WG1), Sustainability and Legacy (WG2),

Differentiation of the Olympic Games (WG3), Procedure for the

Composition of the Olympic Games (WG4), Olympic Games Management (WG5),

Protecting Clean Athletes (WG6), Olympic TV Channel (WG7), Olympism in

action including Youth Strategy (WG8), Youth Olympic Games (WG9),

Culture Policy (WG10), Good Governance and Autonomy (WG11), Ethics

(WG12), Strategic review of Sponsorship, Licensing and Merchandising

(WG13), IOC Membership (WG14).

As one can easily judge, the

themes covered by these groups are mostly in line with the direction

defined a priori by the IOC for the Olympic Agenda 2020. There is little

sign of a reflection centered on the role and responsibility of the IOC

concerning the enforcement of fundamental rights and standards at the

Olympic Games. Furthermore, the scope of competences of each WG is not

defined rigorously; thereby, leaving substantial room for interpretation

of the scope of remits covering for example fields as broad as

ethics. Surely, independent experts like Hugette Labelle (Director of

Transparency International) and Leonard McCarthy (Integrity

vice-president of the World Bank) are not suspicious of collusion with

the IOC, but will they be enough to tilt the balance in favour of the

societal concerns expressed? This cherry picking of external

personalities supposed to ensure the independence and good faith of the

whole process cannot compensate for its procedural deficiencies. In light of

the secrecy and vagueness surrounding the WGs agenda, competences and

meetings, there is little hope for a responsive reform process to

unfold.

Conclusion: Plus ça change, moins ça change?

The

IOC is at an institutional crossroad. The Olympic Games are being

overtly and loudly contested. Citizens are protesting against their organization, as they have (definitely?) lost their mythical aura and turned into a commercial fair obsessed by

its financial returns. Is this state of play going to change with the new

Olympic Agenda 2020? It is rather unlikely, but anybody keen on

defending the Olympic Games as a unique cosmopolitan and ludic

encounter must speak now or forever hold his peace. Indeed, the outcome

of the process under way will most likely structure the (political,

social, economic) orientations followed by the Olympic Games in the

years to come. An intensification of the hunt for economic returns by

the IOC would estrange it even more from its societal base and surely

intensify the decline of what has been the most successful global

happening ever conceived. Public scrutiny and societal irritation are

more necessary than ever if the change brought forward by the Olympic

Agenda 2020 is to mean real change.