Introduction: FIFA’s TPO ban and its compatibility with EU competition law.

Day 2: Third-party entitlement to shares of transfer fees: problems and solutions

Day 3: The Impact of the TPO Ban on South American Football.

Day 4: Third Party Investment from a UK Perspective.

Day 5: Why FIFA's TPO ban is justified.

Editor's note: This is the first blog of our symposium on FIFA's TPO ban, it features the position of La Liga regarding the ban and especially highlights some alternative regulatory measures it would favour. La Liga has launched a complaint in front of the European Commission challenging the compatibility of the ban with EU law, its ability to show that realistic less restrictive alternatives were available is key to winning this challenge. We wish to thank La Liga for sharing its legal (and political) analysis of FIFA's TPO ban with us.

INTRODUCTION

The Spanish Football League (La Liga) has argued for months that the funding of clubs through the conveyance of part of players' economic rights (TPO) is a useful practice for clubs. However, it also recognized that the

practice must be strictly regulated. In July 2014, it approved a provisional regulation that was sent to many of the relevant stakeholders, including FIFA’s Legal Affairs Department. More...

The world of professional cycling and doping have been closely intertwined

for many years. Cycling’s International governing Body, Union Cycliste

Internationale (UCI), is currently trying to clean up the image of the sport

and strengthen its credibility. In order to achieve this goal, in January 2014

the UCI established the Cycling Independent Reform Commission (CIRC) “to conduct a wide ranging independent investigation

into the causes of the pattern of doping that developed within cycling and allegations

which implicate the UCI and other governing bodies and officials over

ineffective investigation of such doping practices.”[1] The final report was submitted to the

UCI President on 26 February 2015 and published on the UCI website on 9 March 2015. The report

outlines the history of the relationship between cycling and doping throughout

the years. Furthermore, it scrutinizes the role of the UCI during the years in

which doping usage was at its maximum and addresses the allegations made

against the UCI, including allegations of corruption, bad governance, as well

as failure to apply or enforce its own anti-doping rules. Finally, the report turns

to the state of doping in cycling today, before listing some of the key practical

recommendations.[2]

Since the day of publication, articles and commentaries (here and here) on the report have been burgeoning and many

of the stakeholders have expressed their views (here and here). However, given the fact that the report is

over 200 pages long, commentators could only focus on a limited number of

aspects of the report, or only take into account the position of a few

stakeholders. In the following two blogs we will try to give a comprehensive

overview of the report in a synthetic fashion.

This first blogpost will focus on the relevant findings and

recommendations of the report. In continuation, a second blogpost will address

the reforms engaged by the UCI and other long and short term consequences the

report could have on professional cycling. Will the recommendations lead to a

different governing structure within the UCI, or will the report fundamentally

change the way the UCI and other sport governing bodies deal with the doping

problem? More...

'Can't fight corruption with con tricks

They use the law to commit crime

And I dread, dread to think what the future

will bring

When we're living in gangster time'

The Specials - Gangsters

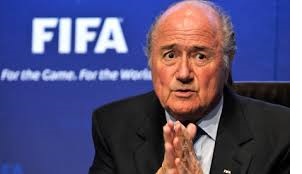

The pressing need for change

The

Parliamentary Assembly (PACE) of the Council of Europe (CoE), which is composed

of 318 MPs chosen from the national parliaments of the 47 CoE member states,

unanimously adopted a report entitled ‘the reform of

football’

on January 27, 2015. A draft resolution on the report will be debated during the

PACE April 2015 session and, interestingly, (only?) FIFA’s president Sepp

Blatter has been sent an invitation.

The PACE report

highlights the pressing need of reforming the governance

of football by FIFA and UEFA respectively. Accordingly, the report contains

some interesting recommendations to improve FIFA’s (e.g., Qatargate[1]) and

UEFA’s governance (e.g., gender representation). Unfortunately, it remains unclear

how the report’s recommendations will actually be implemented and enforced.

The report is a

welcomed secondary effect of the recent Qatargate directly involving former

FIFA officials such as Jack Warner, Chuck Blazer, and Mohamed Bin Hammam[2] and

highlighting the dramatic failures of FIFA’s governance in putting its house in

order. Thus, it is undeniably time to correct the governance of football by FIFA

and its confederate member UEFA – nolens

volens. The real question is how to do it.

Photograph:

Fabrice Coffrini/AFP/Getty Images Photograph:

Octav Ganea/AP

More...

On 15

April 2014, the Cairo Economic Court (the “Court") issued a seminal

judgment declaring the broadcasting of a football match a sovereign act of State.[1]

Background

In Al-Jazeera

v. the Minister of Culture, Minister of Information, and the Chairman of the

Board of Directors of the Radio and Television Union, a case registered

under 819/5JY, the Al-Jazeera TV Network (the “Plaintiff” or “Al-Jazeera”)

sued the

Egyptian Radio and Television Union (“ERTU” or the “Union”) et

al. (collectively, the “Respondents”) seeking compensation for

material and moral damages amounting to three (3) million USD, in addition to

interest, for their alleged breach of the Plaintiff’s exclusive right to

broadcast a World Cup-qualification match in Egypt. Al-Jazeera obtained such

exclusive right through an agreement it signed with Sportfive, a sports marketing company that had

acquired the

right to broadcast Confederation of African Football (“CAF”) World

Cup-qualification matches.

ERTU

reportedly broadcasted the much-anticipated match between Egypt and Ghana live on

15 October 2013 without obtaining Al-Jazeera’s written approval, in violation

of the Plaintiff’s intellectual property rights.

More...

The selling of media rights is currently a hot

topic in European football. Last week, the English Premier League cashed in

around 7 billion Euros for the sale of its live domestic media rights (2016 to

2019) – once again a 70 percent increase in comparison to the previous tender. This

means that even the bottom club in the Premier League will receive

approximately €130 million while the champions can expect well over €200

million per season.

The Premier League’s new deal has already led

the President of the Spanish National Professional Football League (LNFP),

Javier Tebas, to express his concerns that this could see La Liga lose its position as one of Europe’s leading leagues. He reiterated

that establishing a centralised sales model in Spain is of utmost importance,

if not long overdue.

Concrete plans to reintroduce a system of joint

selling for the media rights of the Primera

División, Segunda División A, and la

Copa del Rey by means of a Royal Decree were already announced two years

ago. The road has surely been long and bumpy. The draft Decree is finally on

the table, but now it misses political approval. All the parties involved are

blaming each other for the current failure: the LNFP blames the Sport

Governmental Council for Sport (CSD) for not taking the lead; the Spanish Football

Federation (RFEF) is arguing that the Federation and non-professional

football entities should receive more money and that it should have a stronger

say in the matter in accordance with the FIFA Statutes; and there are widespread rumours that the two big earners, Real Madrid and FC Barcelona, are actively

lobbying to prevent the Royal Decree of actually being adopted.

To keep the soap opera drama flowing, on 30 December 2014, FASFE (an

organisation consisting of groups of fans, club members, and minority

shareholders of several Spanish professional football clubs) and the

International Soccer Centre (a movement that aims to obtain more balanced and

transparent football and basketball competitions in Spain) filed an antitrust complaint with the European Commission against the LNFP. They

argue that the current system of individual selling of LNFP media rights, with

unequal shares of revenue widening the gap between clubs, violates EU

competition law.

Source:http://www.gopixpic.com/600/buscar%C3%A1n-el-amor-verdadero-nueva-novela-de-televisa/http:%7C%7Cassets*zocalo*com*mx%7Cuploads%7Carticles%7C5%7C134666912427*jpg/

More...

Class actions are among the most

powerful legal tools available in the US to enforce competition rules. With more

than 75 years of experience, the American system offers valuable lessons about

the benefits and drawbacks of class actions for private enforcement in

competition law. Once believed of

as only a US phenomenon, class actions are slowly becoming reality in the EU. After the

adoption of the Directive on damages

actions in November 2014, the legislative initiative in collective redress

(which could prescribe a form of class actions) is expected in 2017.[1]

Some

pro-active Member States have already taken steps to introduce class actions in

some fashion, like, for example, Germany.

What

is a class action? It is a lawsuit that allows

many similar legal

claims with a common interest to be bundled into a single

court action. Class actions facilitate

access to justice for potential claimants, strengthen the negotiating power and

contribute

to the efficient administration of justice. This legal mechanism

ensures a possibility to claim cessation of

illegal behavior (injunctive relief) or to claim compensation for damage

suffered (compensatory relief). More...

There has been a lot

of Commission interest in potential state aid to professional football

clubs in various Member States. The huge

sums of money involved are arguably an important factor in this interest and

conversely, is perhaps the reason why state aid in rugby union is not such a

concern. But whilst the sums of money

may pale into comparison to those of professional football, the implications

for the sport are potentially no less serious.

At the end of the

2012/2013 season, Biarritz Olympique (Biarritz) were relegated from the elite

of French Rugby Union, the Top 14 to the Pro D2. By the skin of their teeth, and as a result

of an injection of cash from the local

council (which amounted

to 400,000€), they were spared administrative relegation to the amateur league

below, the Fédérale 1, which would have occurred as a result of the financial

state of the club.More...

Introduction

The year 2015 promises to be crucial, and possibly revolutionary, for

State aid in football. The European Commission is taking its time in concluding

its formal investigations into alleged State aid granted to five Dutch clubs

and several Spanish clubs, including Valencia CF and Real Madrid, but the final decisions are due for 2015.

A few months ago, the Commission also received a set of fresh State aid complaints originating from the EU’s newest Member State

Croatia. The complaints were launched by a group of minority shareholders of

the Croatian football club Hajduk Split, who call themselves Naš Hajduk. According to Naš Hajduk, Hajduk Split’s eternal rival, GNK Dinamo

Zagreb, has received more than 30 million Euros in unlawful aid by the city of

Zagreb since 2006.More...

Media reports and interested stakeholders often suggest that

certain types of sports bets would significantly increase the risks of match

fixing occurring. These concerns also surface in policy discussions at both the national and European level.

Frequently calls are made to prohibit the supply of “risky” sports bets as a

means to preserve the integrity of sports competitions.

Questions about the appropriateness of imposing such

limitations on the regulated sports betting, however, still linger. The

lack of access to systematic empirical evidence on betting-related match fixing

has so far limited the capacity of academic research to make a proper risk

assessment of certain types of sports bets.

The ASSER International Sports Law Centre has conducted the first-ever study that assesses the integrity risks of certain sports bets on the

basis of quantitative empirical evidence.

We uniquely obtained access to key statistics from

Sportradar’s Fraud Detection System (FDS). A five-year dataset of football

matches worldwide, which the FDS identified as likely to have been targeted by

match fixers, enabled us to observe patterns and correlations with certain

types of sports bets. In addition, representative samples of football bets

placed with sports betting operator Betfair were collected and analysed.

The results presented in this report, which challenge several claims

about the alleged risks generated by certain types of sports bets, hope to

inform policy makers about the cost-effectiveness of imposing limits on the

regulated sports betting offer.More...