No language without history

Published 7 January 2019by Julia van der Krieke

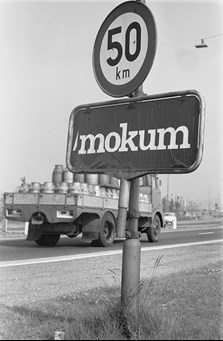

“Mokum” is the Yiddish word for Amsterdam, which shows the strong connection of the city with its Yiddish heritage. © Shutterstock

While words are carriers of meaning, they are likewise markers of cultural heritage. The Dutch language, like most European languages, has borrowed from other vocabularies. Jewish heritage therefore became embedded in our language too. Most everyday words in Dutch that come from Yiddish, such as mazzel, tof, or mesjogge easily betray the Jewishness of their roots. But what about other commonly used terms? Jatten (stealing) for instance derives from yad (hand). Bolleboos (smarty-pants) comes from the Hebrew expression ba’al ha Bayit, or master of the house. But also other languages influenced the Dutch, it is nearly impossible to find someone who knows a Dutch alternative for the French word paraplu, used for umbrella. The Dutch coat of arms Je maintaindrai, is French. E-mail seems by now to have been around forever, just as plastic, per se or restaurant. At times, new words are invented to keep out other influences, as with the French ordinateur, the Hebrew machshev (מַחשֵׁב), the Basque ordenagailu or Welsh cyfrifiadur, all meaning computer. Yiddish speakers were apparently fine with the innovation and stuck to קאָמפּיוטער, pronounced almost the same as “computer”.

That so many of our words stem from other cultural traditions means that we have not lived in isolation from one another. Globalisation and migration are not modern phenomena. Looking at Amsterdam, it was already wildly multicultural in the seventeenth century and those who wanted to be part of society, especially with regard to the bustling sea trade and work in various other trades, learned to speak multiple languages. Visitors frequently noted the high literacy in the Netherlands, in particular the literacy of women. Amsterdam correspondingly became one of the most important printing centres, allowing books to become widespread.

Overseas, the Dutch language had influence too. In Russian, a great number of words dealing with seafaring are originally Dutch, such as матрос, in Dutch matroos (sailor), штурвал corresponding with the Dutch stuurwiel (steering wheel) and макрель, makreel (mackerel). In American English, Dutch can be heard through cookie (koekje), rucksack (rugzak), iceberg (ijsberg), and of course, the iconic Yankee, deriving from the Dutch name Jan Kees, used to mock revolutionaries but now commonly used to describe Americans in general.

Back to Yiddish, a Germanic language like Dutch, German and English, but with Semitic, Roman and Slavic influences, spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. Spoken since the 9th century, the earliest documents known are from the 12th century CE. On the one hand, Yiddish is associated with the Talmud, bringing a religious connotation that one might feel listening to Hasidic Jews from Jerusalem, Antwerp or Brooklyn. However, Yiddish has a secular side that was cultivated in the marketplace, in literature, jokes and on the streets, also those of Amsterdam. Yiddish survived, albeit with far fewer speakers. The Shoah and suppression under Soviet rule are debit to this.

In 1817, it became forbidden to teach in Yiddish at Jewish schools in the Netherlands. The idea was to help integrate students of poorer Jewish schools into Dutch society, teaching pupils Dutch and Hebrew, instead. In practice, this took time as most teachers did not speak Dutch themselves, coming from Poland or Germany. After about twenty years, the measure was finally officially implemented, causing the new generation of Jews to become fluent in Dutch.

In 1817, it became forbidden to teach in Yiddish at Jewish schools in the Netherlands. The idea was to help integrate students of poorer Jewish schools into Dutch society, teaching pupils Dutch and Hebrew, instead. In practice, this took time as most teachers did not speak Dutch themselves, coming from Poland or Germany. After about twenty years, the measure was finally officially implemented, causing the new generation of Jews to become fluent in Dutch.

Nonetheless, Yiddish remains part of the Dutch language until today. Just as Americans using words like nosh, shlep, schnozz or schmooze, we Dutch speak of kapsones, bajes, stiekem, kloffie, habbekrats, pleite and lef. There even exist rumours that the most Dutch word of all, fiets (bicycle), might derive from Yiddish taking over from the now old-fashioned Dutch word rijwiel. In addition, some words seem Yiddish, like schorem, or scum, but turn out to be cant or vernacular. Through language, Amsterdam stayed connected to its Ashkenazi heritage. And while Ladino or Judaeo-Spanish seems not to have had a lasting impact on the Dutch language, Mokum is still synonymous with Amsterdam today, signifying the Global city it inspires to be. (Photo above is taken from the National Archives in the Hague).

In ‘The Other Within’, a scholarly work by Yirmiyahu Yovel, it is exemplified how language always contains traces of stories, this one focusing on Sephardic heritage. Yovel describes how a Spaniard mumbles a sentence walking into a Church, explaining that although he does not know the meaning of the sentence, pronouncing it is a tradition in his family. Someone near him then recognises the sentence as a commandment from the Bible book Deuteronomy. The man was actually cursing the church he entered, as his forefathers, conversos, or Jews forced into Catholicism, had taught one another to do. History is always there, there is no language without it. The past and the present connect us.