African blacks and Mulattos in the 17th-Century Amsterdam Portuguese Jewish community

Published 2 December 2019By Yehonatan Elazar-DeMota

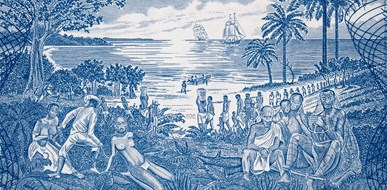

The analysis of the early 17th-century minutes of the Portuguese Jewish community, published in Amsterdam sheds light on their use of black African slaves on Dutch soil. ©Shutterstock

The seventeenth-century Portuguese Jewish community in Amsterdam was comprised of members coming from Spain, Portugal, Italy, Turkey, Greece, France, Belgium, Morocco, and West Africa. José Da Silva Horta and Peter Mark (2011) found records of Sephardic communities along the West coast of Africa. The archival records reveal the reality of slave trade. Portuguese conversos [coerced Jewish converts to Catholicism] had been slave trading since the sixteenth century between Lisbon, Sevilla, the Atlantic islands, and West Africa. They even managed to control the asientos [contracts permitting the sell of slaves in the Spanish colonies] between 1580 and 1640. The most prominent slave traders were from the families: Rodrigues, Jiménez, Noronha, Mendes, Pallos Dias, Caballero, Jorge, Fernandes Elvas, and Caldeira. The members of these families established an international network based on national-religious ties and kinship.

When the Nação [Hebrews of the Portuguese Nation] members began arriving to the Netherlands, often time they brought their African ‘servants’ with them. Even though the practice of slavery was illegal in the Netherlands, Portuguese Jews called them ‘servants.’ According to halakhah [Jewish law], a slave owned by a Jew had to undergo a ritual at the beginning and the end of his or her service. This ritual included circumcision [for men] and a ritual bath [men and women]. This permitted Jews to have slaves for a period of twelve months, after which the slave became a full-fledged Jew. However, if the slave did not voluntarily embrace the Jewish faith, the owner was obligated to sell his or her slave to non-Jews. One way to circumvent this was by giving the slave to another Jew as a gift, before the expiration of the twelve months. Inquisitorial archives in Torre do Tombo [Portugal] and the Canary Islands reveal this practice among the Sephardim. But what happened to those African blacks in Amsterdam that did not embrace the Jewish faith?

The communal records of the early Portuguese Jewish community in Amsterdam show that it was becoming a problem to deal with their African servants who did not become part of the community. In 1627 [Hebrew year 5387], the Ma’amad [board of trustees] gathered at the house of Benjamin de Israel in order to establish regulations on behalf of the community. The regulations provide evidence of the problem of the non-Jewish African blacks:

First, that no negro or mulatto will be able to be buried in the cemetery except for those who had buried in it a Jewish mother;…And further…that none shall persuade any of the said negros and mulattos, man or woman, or any other person who is not of the nation of Israel to be made Jews; and it is particularly recommended to all men of the Law that they not admit them, just as people who have a [private] miqveh [ritual bath] not immerse them without the permission of the Gentlemen of the Board of directors, for in this way…results in only scandal and offense to God; he who does the contrary, measures will be taken against him as disobedient.[GAA, 334, no. 13, fol. 42].

This ordinance makes public that some Sephardic Jews had contact with dark-skinned Africans in Amsterdam. It also demonstrates that some men of the Nação had children [mulatto] with women from the African community therein. In addition, it unveils that previous to this ruling, congregants were accustomed to proselytizing their African servants, especially those with their own ritual-bath houses. The fact that provisions for the burial of slaves in the Jewish cemetery were made, reveals that Sephardic merchants in Amsterdam must have owned slaves therein. Since the use of dark-skinned African slaves was not customary on Dutch soil at the time, the Sephardim probably wanted to draw as little attention to themselves as possible. Lydia Hagoort attests to the fact that the Portuguese word for slave [escravo] disappeared from the Beth Ḥaim records around ‘the beginning of the seventeenth century, possibly to avoid controversy about the ambivalent status of slaves. As long as these slaves became Jews at the end of their services, the Nação would be able to continue this practice, without incurring any penalties from the city authorities.

The Great Council of Mechelen decided in the sixteenth century that enslaved peoples entering the Low Countries were to be freed, regardless of religion. This decision led to the development of the so-called ‘free-soil’ tradition in the Netherlands. The jurists: Groenewegen van der Made (1613 —1652), Clenardus (1495 – 1542), Molanus (1533 – 1585), Gudelinus (1550 – 1619), developed the ‘free soil’ idea in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This notion was put to test time-after-time, especially when merchants would arrive to the United Provinces with enslaved peoples. In 1626, four Nação merchants arrived to Amsterdam with black African slaves. The municipal records [GAA. NA, 5075, No. 3402. 19 Feb. 1626] state that they were allowed to stay in the Netherlands for three months, after which they left to Bayonne with their ‘property.’ It wasn’t until 1654, that the municipality of Amsterdam made a provision in Chapter 39 of its laws, mirroring the provision of in Article 36 of Antwerp:

I.Within the city and surroundings of Antwerp, all people are free and no slaves.

II. The same holds true for all slaves that have come to the city and its surroundings, who are free and outside of the power of their Masters or Wives: and as far as they try to keep them as slaves or have them serve them against their will may proclaim ad libertatem patriae; and can have their Masters or Wives brought before court and can have themselves proclaimed free there.

The fact that slaves could bring their masters to court, demonstrates that they had legal persona. Nonetheless, enslaved persons in the Netherlands had to appeal; liberty was not granted automatically. Certainly, the nascent Portuguese Jewish community was aware of this law. This is perhaps why they establish a communal ordinance (1650) that no negros nor mulattos will be circumcised, nor immersed any longer. Evidently, the Sephardic community in Amsterdam did not want to be held accountable for violating the ius commune [law of the land]. While this ruling protected the legal character of the Jewish community, it also provided a justification for them to keep perpetual ‘servants’ within the community. Furthermore, this ruling became the model for the diaspora Nação communities in the Caribbean. In that context, the lack of circumcision (male) and immersion (male and female) for sub-Saharan slaves, sealed their destiny as perpetual slave workers on the plantations