Editor's note: Marjolaine is a researcher and attorney admitted to the Geneva bar (Switzerland) who specialises in sports and life sciences.

On 25 August 2020, the Swiss Supreme Court

(Swiss Federal Tribunal, SFT) rendered

one of its most eagerly awaited decisions of 2020, in the matter of Caster

Semenya versus World Athletics (formerly and as referenced in the decision:

IAAF) following an award of the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS). In short,

the issue at stake before the CAS was the validity of the World

Athletics eligibility rules for Athletes with Differences of Sex Development

(DSD Regulation). After the CAS upheld their validity in an award

of 30 April 2019, Caster Semenya and the South African Athletics Federation

(jointly: the appellants) filed an application to set aside the award before

the Swiss Supreme Court.[1]

The SFT decision, which rejects the application, was made public along with a

press release on 8 September 2020.

There is no doubt that we can expect contrasted

reactions to the decision. Whatever one’s opinion, however, the official

press release in English does not do justice to the 28-page long decision

in French and the judges’ reasoning. The goal of this short article is

therefore primarily to highlight some key extracts of the SFT decision and some

features of the case that will be relevant in its further assessment by

scholars and the media.[2]

It is apparent from the decision that the

SFT was very aware that its decision was going to be scrutinised by an

international audience, part of whom may not be familiar with the mechanics of

the legal regime applicable to setting aside an international arbitration award

in Switzerland.

Thus, the decision includes long

introductory statements regarding the status of the Court of Arbitration for

Sport, and the role of the Swiss Federal Tribunal in reviewing award issued by

panels in international arbitration proceedings. The SFT also referred

extensively throughout its decision to jurisprudence of the European Court of

Human Rights (ECtHR), rendered in cases related to international sport and the

CAS. More...

Editor’s note: Josep F. Vandellos Alamilla is an

international sports lawyer and academic based in Valencia (Spain) and a member

of the Editorial Board of the publication Football Legal. Since 2017 he is the

Director of the Global Master in Sports

Management and Legal Skills FC Barcelona – ISDE.

I think we would all agree that the reputation of

players’ agents, nowadays called intermediaries, has never been a good one for

plenty of reasons. But the truth is their presence in the football industry is

much needed and probably most of the transfers would never take place if these

outcast members of the self-proclaimed football

family were not there to ensure a fluid and smooth communication between all

parties involved.

For us, sports lawyers, intermediaries are also

important clients as they often need our advice to structure the deals in which

they take part. One of the most recurrent situations faced by intermediaries and

agents operating off-the-radar (i.e. not registered in any football association

member of FIFA) is the risk of entering in a so-called multiparty or dual representation

and the potential risks associated with such a situation.

The representation of the interests of multiple

parties in football intermediation can take place for instance when the agent represents

the selling club, the buying club and/or the player in the same transfer, or when

the agent is remunerated by multiple parties, and in general when the agent incurs

the risk of jeopardizing the trust deposited upon him/her by the principal. The

situations are multiple and can manifest in different manners.

This article will briefly outline the regulatory

framework regarding multiparty representation applicable to registered

intermediaries. It will then focus on provisions of Swiss law and the

identification of the limits of dual representation in the light of the CAS

jurisprudence and some relevant decisions of the Swiss Federal Tribunal.More...

Editor’s Note: Shervine Nafissi (@SNafissi) is a Phd Student in sports law and teaching assistant in corporate law at University of Lausanne (Switzerland), Faculty of Business and Economics (HEC).

Introduction

The factual background

The dispute concerns a TPO contract entitled “Economic Rights Participation Agreement” (hereinafter “ERPA”) concluded in 2012 between Sporting Lisbon and the investment fund Doyen Sports. The Argentine player was transferred in 2012 by Spartak Moscow to Sporting Lisbon for a transfer fee of €4 million. Actually, Sporting only paid €1 million of the fee while Doyen Sports financed the remaining €3 million. In return, the investment company became the owner of 75% of the economic rights of the player.[1] Thus, in this specific case, the Portuguese club was interested in recruiting Marcos Rojo but was unable to pay the transfer fee required by Spartak Moscow, so that they required the assistance of Doyen Sports. The latter provided them with the necessary funds to pay part of the transfer fee in exchange of an interest on the economic rights of the player.

Given that the facts and circumstances leading to the dispute, as well as the decision of the CAS, were fully described by Antoine Duval in last week’s blog of Doyen vs. Sporting, this blog will solely focus on the decision of the Swiss Federal Supreme Court (“FSC”) following Sporting’s appeal against the CAS award. As a preliminary point, the role of the FSC in the appeal against CAS awards should be clarified.More...

Editor’s note: Professor

Mitten is the Director of the National Sports Law Institute and the LL.M. in

Sports Law program for foreign lawyers at Marquette University Law School in

Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He currently teaches courses in Amateur Sports Law, Professional

Sports Law, Sports Sponsorship Legal and Business Issues Workshop, and Torts.

Professor Mitten is a member of the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS),

and has served on the ad hoc Division for the XXI Winter Olympic Games in Sochi,

Russia.

This Book Review is published at 26 Marquette Sports Law Review 247 (2015).

This

comprehensive treatise of more than 700 pages on the Code of the Court of

Arbitration for Sport (CAS) (the Code) is an excellent resource that is useful

to a wide audience, including attorneys representing parties before the CAS,

CAS arbitrators, and sports law professors and scholars, as well as

international arbitration counsel, arbitrators, and scholars. It also should be of interest to national

court judges and their law clerks because it facilitates their understanding of

the CAS arbitration process for resolving Olympic and international sports

disputes and demonstrates that the Code provides procedural fairness and

substantive justice to the parties, thereby justifying judicial recognition and

enforcement of its awards.[1]

Because the Code has been in existence

for more than twenty years—since November 22, 1994—and has been revised four

times, this book provides an important and much needed historical perspective

and overview that identifies and explains well-established principles of CAS

case law and consistent practices of CAS arbitrators and the CAS Court Office. Both authors formerly served as Counsel to

the CAS and now serve as Head of Research and Mediation at CAS and CAS

Secretary General, respectively, giving them the collective expertise and

experience that makes them eminently well-qualified to research and write this

book.More...

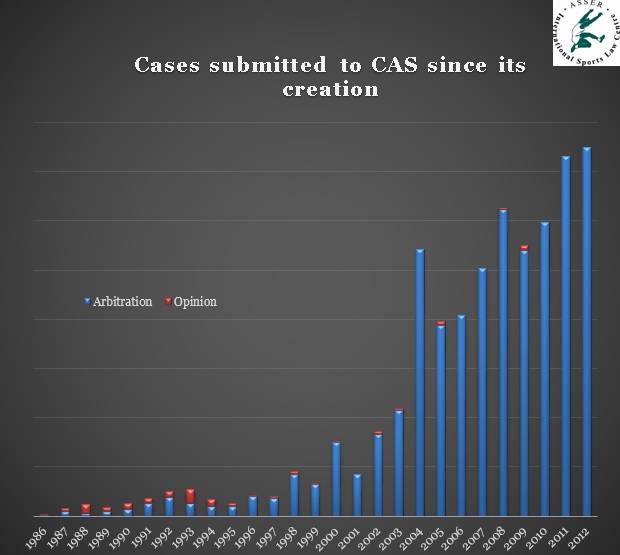

Graph 1: Number of Cases submitted to CAS (CAS Satistics)

More...