Editor’s note: Kester Mekenkamp is an LL.M. student in European Law

at Leiden University and an intern at the ASSER International Sports Law

Centre. This blog is, to a great extent, an excerpt of his forthcoming master

thesis.

On 24 November

2016, a claim was

lodged before a Zurich commercial court against FIFA’s transfer regulations by

a 17-year-old African football player.[1]

The culprit, according to the allegation: The provision on the protection of

minors, Article 19 of the Regulations

for the Status and Transfer of Players.[2]

The claimant and his parents dispute the validity of this measure, based on the

view that it discriminates between football players from the European Union and

those from third countries. Besides to Swiss cartel law, the claim is

substantiated on EU citizenship rights, free movement and competition law. Evidently,

it is difficult to assess the claim’s chance of success based on the sparse information

provided in the press.[3]

Be that as it may, it does provide for an ideal (and unexpected) opportunity to

delve into the fascinating subject of my master thesis on FIFA’s regulatory

system aimed at enhancing the protection of young football players and its

compatibility with EU law. This three-part blog shall therefore try to provide

an encompassing overview of the rule’s lifespan since its inception in 2001. More...

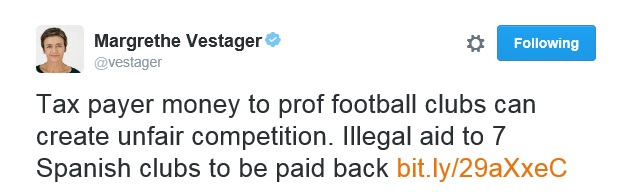

On 28 September 2016, the Commission published the

non-confidential version of its negative Decision and recovery order regarding the preferential

corporate tax treatment of Real Madrid, Athletic Bilbao, Osasuna and FC

Barcelona. It is the second-to-last publication of the Commission’s Decisions

concerning State aid granted to professional football clubs, all announced on 4 July of this year.[1]

Contrary to the other “State aid in football” cases, this Decision concerns

State aid and taxation, a very hot topic in

today’s State aid landscape. Obviously, this Decision will not have the same

impact as other prominent tax decisions, such as the ones concerning Starbucks and Apple.

Background

This case dates back to November 2009, when a representative

of a number of investors specialised in the purchase of publicly listed shares,

and shareholders of a number of European football clubs drew the attention of

the Commission to a possible preferential corporate tax treatment of the four

mentioned Spanish clubs.[2]More...

It’s been a long wait, but they’re finally here!

On Monday, the European Commission released its decisions regarding State aid to seven Spanish professional football clubs (Real Madrid on two occasions) and five Dutch professional football clubs. The decisions mark the end of the formal

investigations, which were opened in 2013. The Commission decided as follows:

no State aid to PSV Eindhoven (1); compatible aid to the Dutch clubs FC Den

Bosch, MVV Maastricht, NEC Nijmegen and Willem II (2); and incompatible aid granted

to the Spanish football clubs Real Madrid, FC Barcelona, Valencia CF, Athletic

Bilbao, Atlético Osasuna, Elche and Hércules (3).

The recovery decisions in particular are truly historic.

The rules on State aid have existed since the foundation of the European

Economic Community in 1958, but it is the very first time

that professional football clubs have been ordered to repay aid received from

(local) public authorities.[1]

In a way, these decisions complete a development set in motion with the Walrave

and Koch ruling of 1974, where

the CJEU held that professional sporting activity, and therefore also football,

is subject to EU law. The landmark Bosman case of 1995 proved to be of great significance as

regards free movement of (professional) athletes and the Meca-Medina case of 2006 settled that EU competition rules were

equally applicable to the regulatory activity of sport. The fact that the first

ever State aid recovery decision concerns major clubs like Real Madrid, FC

Barcelona and Valencia, give the decisions extra bite. Therefore, this blog

post will focus primarily on the negative/recovery decisions[2],

their consequences and the legal remedies available to the parties involved.[3]

More...

The selling of media rights is currently a hot

topic in European football. Last week, the English Premier League cashed in

around 7 billion Euros for the sale of its live domestic media rights (2016 to

2019) – once again a 70 percent increase in comparison to the previous tender. This

means that even the bottom club in the Premier League will receive

approximately €130 million while the champions can expect well over €200

million per season.

The Premier League’s new deal has already led

the President of the Spanish National Professional Football League (LNFP),

Javier Tebas, to express his concerns that this could see La Liga lose its position as one of Europe’s leading leagues. He reiterated

that establishing a centralised sales model in Spain is of utmost importance,

if not long overdue.

Concrete plans to reintroduce a system of joint

selling for the media rights of the Primera

División, Segunda División A, and la

Copa del Rey by means of a Royal Decree were already announced two years

ago. The road has surely been long and bumpy. The draft Decree is finally on

the table, but now it misses political approval. All the parties involved are

blaming each other for the current failure: the LNFP blames the Sport

Governmental Council for Sport (CSD) for not taking the lead; the Spanish Football

Federation (RFEF) is arguing that the Federation and non-professional

football entities should receive more money and that it should have a stronger

say in the matter in accordance with the FIFA Statutes; and there are widespread rumours that the two big earners, Real Madrid and FC Barcelona, are actively

lobbying to prevent the Royal Decree of actually being adopted.

To keep the soap opera drama flowing, on 30 December 2014, FASFE (an

organisation consisting of groups of fans, club members, and minority

shareholders of several Spanish professional football clubs) and the

International Soccer Centre (a movement that aims to obtain more balanced and

transparent football and basketball competitions in Spain) filed an antitrust complaint with the European Commission against the LNFP. They

argue that the current system of individual selling of LNFP media rights, with

unequal shares of revenue widening the gap between clubs, violates EU

competition law.

Source:http://www.gopixpic.com/600/buscar%C3%A1n-el-amor-verdadero-nueva-novela-de-televisa/http:%7C%7Cassets*zocalo*com*mx%7Cuploads%7Carticles%7C5%7C134666912427*jpg/

More...

The summer saga surrounding Luis

Suarez’s vampire instincts is long forgotten, even though it might still play a

role in his surprisingly muted football debut in FC Barcelona’s magic triangle.

However, the full text of the CAS award in the Suarez

case has recently be made available on CAS’s website and we want to grasp this

opportunity to offer a close reading of its holdings. In this regard, one has

to keep in mind that “the object of the appeal is not to request the complete

annulment of the sanction imposed on the Player” (par.33). Instead, Suarez and

Barcelona were seeking to reduce the sanction imposed by FIFA. In their eyes, the

four-month ban handed out by FIFA extending to all football-related activities

and to the access to football stadiums was excessive and disproportionate. Accordingly,

the case offered a great opportunity for CAS to discuss and analyse the

proportionality of disciplinary sanctions based on the FIFA Disciplinary Code (FIFA DC). More...

In the same week that saw Europe’s best eight teams compete in the

Champions League quarter finals, one of its competitors received such a severe

disciplinary sanction by FIFA that it could see its status as one of the

world’s top teams jeopardized. FC Barcelona, a club that owes its success both

at a national and international level for a large part to its outstanding youth academy, La Masia, got to FIFA’s attention for breaching FIFA

Regulations on international transfers of minors. More...